The following sections are a composite reconstruction of the way the Inca empire existed at its height. Due to the large amount of archaeological work done on Inca occupations in their provinces, variation in Inca practices can be identified. It is now clear that the monolithic view of the Inca as having a one-size-fits-all imperial rule is incorrect. The Incas tailored their ideal model of statecraft to the particular circumstances of individual conquered ethnicities. Still, discussing the model as it has been generated from the ethnohistorical records is useful as a starting point.

Social Structure

The basic unit of Inca society and most others that they conquered was the household. This was a residential unit that lived together, and typically consisted of a nuclear family and unmarried adults. Households belonged to ‘ayllus’, groups of families that shared a common ancestor and place of origin, and often shared labor in subsistence activities. Ayllus were typically grouped into two parts, in Quechua, the language of the Incas, called ‘hanan’ (upper) and ‘hurin’ (lower). These divisions were largely for ritual purposes, though they also allowed larger groups within a community to participate and divide labor equitably, such as to clean out an irrigation canal or reservoir.

For the Incas of the Cuzco region, social structure and status were based on the relationship to the founding kings. Each king founded a new ayllu that included the king, his wives, and their children, then subsequently, all their children’s children, etc. The former king’s ayllu became a panaca, a kind of corporate group charged with taking care of the king’s mummy and all his estates and possessions. This occurred because the kings were semi-divine, so required their material goods even after death. The ten royal panaca, each with its king’s mummy, were the highest elite in Inca society.

Below the ten royal panaca were ten non-royal ayllus, which were said by some chroniclers to be the descendants of the people who accompanied Manqo Qhapaq from Pacariqtambo to Cuzco. They enjoyed the status of being elites in Inca society, which allowed them certain privileges not available to commoners. A final elite group in Inca society consisted of the Incas by Privilege. These were ayllus of ethnic groups who lived in the vicinity of Cuzco, and had been drawn into the Incas’ sphere of influence early on. They were treated as Inca nobility, and were therefore able to serve in specific posts in the empire, which is one possible reason for their elevation to Inca status (see below). Below the Inca elites were a level of conquered leaders, called ‘curacas’, who served posts in the Inca political hierarchy. They had duties that were related to the numbers of households under their command, but the more powerful ones had a status that could rank nearly as high as an Inca by Privilege. They could own land, have servants and wear particular kinds of high status clothing. Finally, at the bottom of the social hierarchy were the commoners, the great mass of conquered people with no political leadership positions.

Political Structure

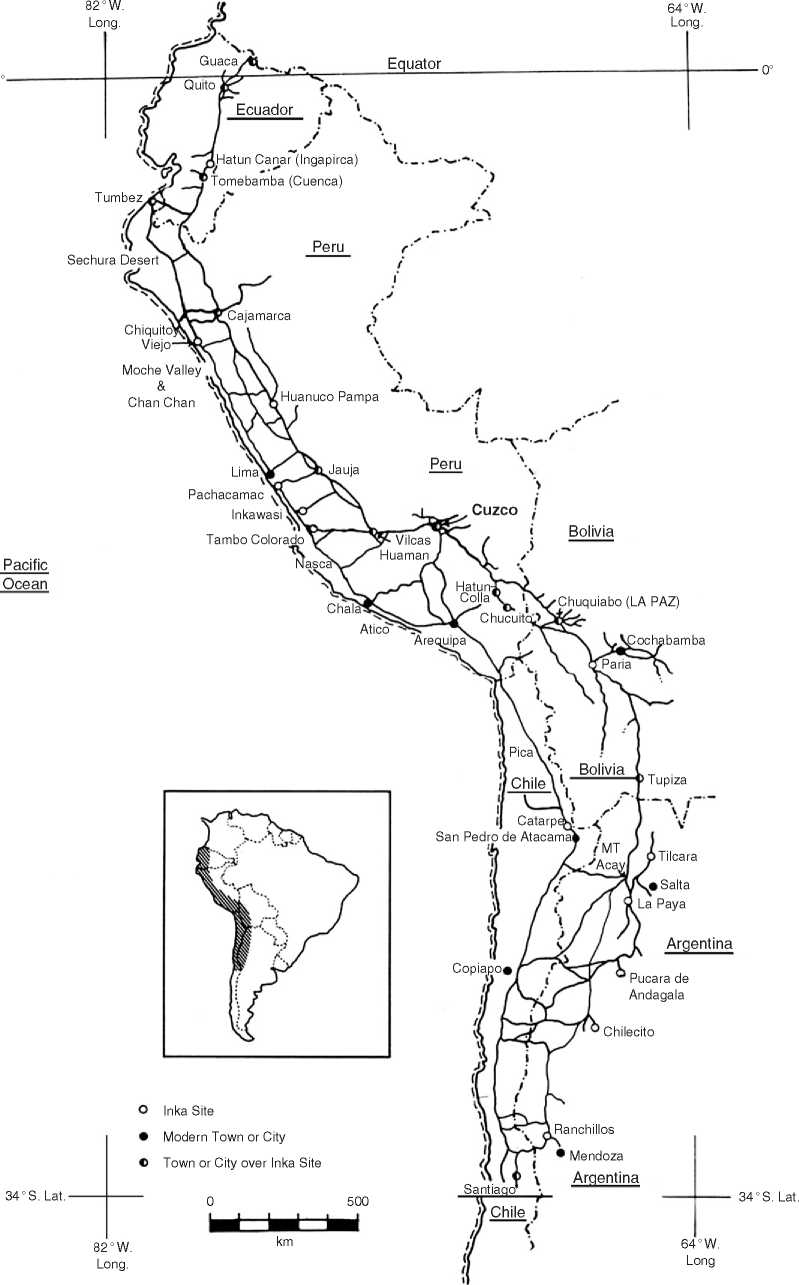

The Incas called their empire Tawantinsuyu, the Four Parts Together. The empire was divided into four parts, Chinchaysuyu, the northern part, Collasuyu, the southern part, and Antisuyu and Cuntisuyu, the eastern and western parts, respectively (Figure 1). As can be seen, the parts were highly unequal, both in terms of geographic area and population. The capital

Figure 1 Map of Inca empire at its greatest extent, with four divisions (suyus) included.

Was Cuzco, the navel of the universe, located at the intersection of the four parts.

Within each suyu, there was a series of provinces, each corresponding roughly to the territory of a conquered group. However, the Inca used a decimal system of administration, and each province was supposed to have either 20 000 or 30 000 households. If a conquered ethnicity had that number, they could form a single province. If it were smaller, it might be lumped with other small ethnicities to make a province; if it were larger, it could be broken into more than one province.

Administratively, the political hierarchy was also organized in decimal units. At the top was the king, the ruler of the entire empire. Below him were four ‘apos’, or suyu heads. Each province had a governor, or ‘tocricoq’. Below the governor were heads of different decimal units of households, in descending order of 10 000, 5000, 1000, 500, 100, 50, and 10. These were the curacas mentioned in the previous section.

It is in the administrative hierarchy that the Incas combined social and political aspects. The curacas were hereditary leaders who served as the decimal official for the appropriate sized number of households that he had ruled before the Inca conquest, if possible. The most able son of a curaca followed his father in that role. However, this only applied to the curacas; the apos were typically close relatives of the king, brothers or uncles, and this was the one position that was not hereditary. Because the intrigues surrounding the designation of a new heir were considerable, the king needed apos who he knew he could trust. Since the descendants of previous kings’ apos might be in opposing factions, this position had to be one made by appointment. Governors were typically of the Inca class and were appointed at first, but then the position became hereditary.

The large number of political officials that were required by this administrative system suggest the reason for the inclusion of local leaders: there simply were not enough capable members of the Inca elite to fill all the positions. With approximately 80 provinces in the empire, this would have meant thousands of individuals were needed. This might also indicate a rationale for the Inca by Privilege group, to help fill the higher levels of the bureaucracy with loyal members of the Inca elite.

The inclusion of local lords was also an effective means to rule, because it meant a local, familiar leader would be in charge of fulfilling the responsibilities of the empire. Local leaders were required to learn Quechua, and their sons, who would inherit their positions, were taken to Cuzco for training in imperial policies, including Quechua, quipu use (see below) and other duties. When their fathers died, the Incas returned new leaders who had better experience and skills to do the empire’s bidding.

Economic Structure

D’Altroy and Earle discuss two kinds of finance systems that were employed by the Incas, staple finance and wealth finance. The former involves the production of food and basic services that allow the empire to maintain itself. The latter refers to special kinds of goods, luxury items mostly, that are restricted to the elite segments of society. Understanding the different ways these two financial systems operated is a key to comprehending the Incas’ success at empire building.

Upon the conquest of a group, the land was divided into three parts, one for the use of the state, one for the Inca religion and one remained for the use of the local population. Camelid herds were divided similarly. It is likely that in many cases this policy was implemented slowly, by using the local population to increase productivity through the construction of new fields and irrigation systems. One part of the conquered people’s responsibility to the Incas was to work the fields of the state and religion first, assuring that the productivity required by the empire was fulfilled. Collectively, this staple finance production is often called an agricultural tax on the conquered people, though it could also be called tribute.

Another part of the responsibility owed to the Incas was labor, an obligatory amount that was called ‘m’ita’. Every household owed the Incas m’ita every year: this was always done in rotation, and directed through the local curaca. What the person did depended on the needs of the empire and the skills of the individual. Much m’ita was fulfilled by simply delivering food from its point of origin to an Inca administrative center. Many men served their m’ita in the army, and it was this system that allowed the Incas to field the large military that achieved success in warfare. Other jobs included construction worker, wood collector, potter, toolmaker as well as many other occupations. All households were required to provide one piece of clothing to the empire as well. This cloth was used by the army and other state officials.

An important feature of m’ita was that a person simply showed up to do the required work. All the necessary materials and tools were provided by the state, and food and drink were provided as well. Thus, no one was required to provide anything of her/his own. When one’s rotation of work was done, one returned home and was replaced by someone else. While much work was locally done, other activities, such as warfare, might require a person to be gone for long periods. To reduce the negative effect this might have on agricultural productivity, other community members were required to do the fieldwork of m’ita laborers.

All of the above refers to the staple finance of the empire. Wealth finance was conducted in a different way. Luxury items, such as jewelry, fine cloth, high quality pottery, and gold and silver objects, were produced in workshops controlled by the Incas. Many of these were in Inca administrative centers, built along the Inca highway as service centers for the empire. The best craftspeople were taken to Cuzco to work directly for the Inca elite of the capital.

Regarding craft production, most crafts were produced either in the households of conquered people, or in the administrative centers. There were some specialized communities where everyone worked in one craft, such as the weaving center at Milliraya northwest of Lake Titicaca. Crafts were generally standardized, both in forms and decorations. Cloth was the most important craft, and three different qualities were made. Decorations included geometric designs, and checkerboard patterns on the finest grade. Pottery had several basic forms, among them the ‘aryballos’, or storage vessel; plates with duck heads and tails, for eating; and beakers for drinking. Designs were largely geometric, as with the textiles, including diamonds and triangles, the fern or feather motif, and bands of decoration separated by large open zones of color. Silver and gold metallurgy was mostly for jewelry and eating utensils, such as plates and cups. Small silver and gold llama figurines were often included in important burials (see below). Copper and bronze were also used, the latter for tools.

All of this economic activity generated enormous amounts of information. In the absence of a writing system, the Incas used a device known as a ‘quipu’ to maintain their records. A quipu is a system of knotted strings that hang from a central cord. The location of the knots, the number of knots and the color of the string all provided information about what was being tracked and where it was from. Special individuals, called ‘quipu camayoqs’, were in charge of this important activity.

Special Categories of People

Both staple and wealth finance required the development of specialized groups of individuals by the state, groups who were full-time workers, not m’ita laborers. The quipu camayoqs were one of these groups. ‘Yanacuna’ were a special group of individuals who were attendants to the Inca elite. These people were not just servants, but could be given positions of responsibility as well. They were recruited from the ranks of conquered people, though using what criteria is unknown. A particularly rebellious group, the Chachapoyas of northern Peru, were often used as yanacunas by the Incas, suggesting it was a way of breaking down ethnic loyalty.

A group of women were selected from among conquered peoples at a young age to serve as ‘acllacuna’. The women did a variety of tasks for the Incas, including food and beer preparation, spinning and weaving of fine cloth and even entertainment. They were schooled in special sectors of administrative centers, and also functioned in religious activities. Acllacuna could also be given as wives to officials as rewards for service well done.

A final special group of workers for the Inca state was the ‘mitimaes’. These were people living away from their place of birth. The Inca moved groups around their empire, both for economic and political reasons. If a region was underutilized for food production, mitimaes might be brought in to increase it. Villages that were rebellious could be moved across the empire to separate them from their ancestral homes, religious places and neighbors. Such mitimaes would also serve economic purposes, generally agricultural work. Mitimaes were not required to do m’ita labor.

Inca Infrastructure

A successful empire must facilitate communications and logistical support for its armies and outposts, and provisions for all its subjects. This requires both food and material to be provided along the main lines of travel. As the empire expanded, the staple and wealth finance systems had to be planned and developed. Like the Romans and other Old World civilizations, the Incas created a large road system, which at its height included over 40 000 km of marked roadway.

The road system actually consisted of two main trunks, a highland one and a coastal one (Figure 2). Connecting roads linked the two across the Andes from north to south. In swampy regions, the roadbed was elevated by infilling with rocks and soil. Chasms formed by rivers were crossed with suspension bridges, and the road rose up the mountainsides with well-placed stone steps. Along the coast where there were fewer obstacles and the terrain was more level, the road might have markers only indicating the direction of the road between river valleys, with more clearly marked entrances and exits from the valleys.

All along the highland trunk was a series of large administrative centers that were in effect small cities. The best preserved of these is Hutinuco Pampa, located in the northern highlands west of the modern city of Hutinuco. Research there indicated the city had a hospitality center for people coming into the city, a large ceremonial plaza in its center, complete with an ‘ushnu’, a platform where rituals could be conducted. Other parts of the city included housing for m’ita workers, craft workshops, an area where acllacuna are thought to have lived and worked, and over 4000 storehouses on a hill overlooking the city. An area of exquisitely fitted stone marks the location of the king’s quarters, a place that included baths and food preparation areas.

The administrative centers were located where they could draw on populations from a wide area, but also provide goods and services for those regions. Hutinuco Pampa, for example, served five different ethnic groups. While the usual flow of goods and labor was into the centers, they also served as buffers against agricultural failure. If a group suffered a severe frost or drought, such that insufficient food was produced to feed the population, they were given food from the storehouses, though they were supposed to repay the food in a year of greater abundance.

The administrative centers were located several days’ walks from each other along the highland trunk. No major center has been found along the coastal road, although there are centers like Incawasi in the Cafiete Valley which was created to provide support for the conquest of the valley. In the region of Chile, there are very few administrative centers the size of Hutinuco Pampa, likely because the population density of conquered people was much less in this desolate vicinity.

Located approximately every 20 km along the roads between the major centers were ‘tambos’, smaller centers that provided some services but on a smaller scale. Travelers along the roads, located about one day’s journey apart, could stop at these centers for food and rest.

The roads were strictly for the use of people on official business, not just anyone. They were used for communications, at least along the main highland road. A system of runners, called ‘chasquis’, was used for sending messages along the road system. Every 6-9 km was a small structure where the runners stayed, and as one approached, he would call out, and another runner would get up to hear the message, then set out running for the next outpost. It is said a message could be sent from Lima to Cuzco in a week, though how messages were prevented from becoming muddled is unclear.

Archaeology of the Provinces

The preceding information is a description of a static system, a snapshot of the empire as it has been described by various Spanish sources. Archaeological research in different regions has indicated that this model is more difficult to corroborate archaeologically than one might expect. The typical indicators of an Inca presence - square houses with trapezoidal niches and doorways, ceramics in the form of arybal-los with diamond or feather patterns, finely fitted stonework - are sometimes difficult to identify. Two examples will serve to illustrate the issues.

John and Theresa Topic found that the presence of the Inca highway running through the province of Huamachuco in northern Peru was the best indicator of the Inca presence, and that new Inca settlements, both tambos and storeroom complexes, were located along the route. They were able to identify the provincial capital as having been located in the modern city of Huamachuco, on several subtle architectural and artifactual pieces of evidence. However, differentiating occupations dating to the Late Horizon, when the Inca had conquered the region, was daunting

Figure 2 The Inca road system. Reprinted from The Inka Road System, Hyslop J (1984), with permission from Elsevier.

Because there were so few good Inca-style ceramics, and so much continuity from earlier styles. The inclusion of ethnohistorical information allowed the Topics to understand the subtle way that the province was organized by the Incas, which would have been difficult without the written sources.

Thomas Lynch identified the major Inca occupations in the region of the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. There he found the highway was again the major indication of Inca presence, and that Inca sites tended to be located along it. Local settlements were found near, but not on, the road. There were no fitted stone constructions anywhere, and the main site, Catarpe Tambo, had relatively few Inca ceramics. In contrast, Inca pottery was common in tambos along the road. The importance of Catarpe was indicated more by the presence of architectural features such as long halls called ‘callancas’ and the orientations of major buildings. With few ethnohistorical records for this region, the fine nuances of imperial control were not able to be distinguished as they could be in areas with more documents, like Huamachuco.

Inca Religion

The Incas had a complex set of religious beliefs, including a host of deities, sacred places, oracles, and ancestor worship. Like many ancient societies, life was a set of actions dictated in large part by religious beliefs. No major decision was made without consulting with the priests about possible outcomes.

The Incas, like many of their contemporaries, had a belief that founding ancestors played a role in the daily affairs of their descendants. For the Incas, these ancestors were the early kings, and their bodies were mummified and maintained by their panacas. As semi-divine, the kings were brought out at important ceremonies, given food and drink, and treated as if they were alive. The ancestors were important in providing good harvests, so their veneration was particularly important to assure the food supply. The major deities of the Incas included a creator god, Wiracocha, Inti, the sun god, and Mama Quilla, the moon goddess, Inti-Illapa, the thunder god, and several celestial gods associated with stars and planets. While Wiracocha created the world, and the other gods, he was not a major figure of reverence, having few if any rituals or temples dedicated to him. In contrast, Inti appears to have been the most important god, at least during the reign of the last few kings. Inti was the god of harvests, which explains something of his importance, and also of warfare. The sun temple in Cuzco, the ‘Coricancha’, was the most important temple in the empire, and all administrative centers likewise had sun temples. Mama Quilla, the moon goddess, was the wife of Inti, and was served by priestesses. Inti Illapa was the god of thunder and lightning, and was associated with rainfall.

Another aspect of Inca religion, and one shared again with many of their contemporaries, was the idea that certain places, called ‘huacas’, were sacred. Many things could be ‘huacas’ - springs, large rocks, tombs, fields, mountains - and not all of them were sacred to all people. Huacas could be of local or national importance. The Incas linked many of the huacas in the vicinity of Cuzco into a complex sacred landscape called the ‘ceque system’. This system was a set of imaginary lines that originated at the Coricancha and radiated out in all four directions. According to Brian Bauer, the lines were not necessarily straight, although that might have been the ideal. The lines were also associated with the four suyus and linked huacas; particular social groups in Cuzco conducted rituals at the huacas along the lines. The schedule of rituals defined a complicated calendar that even experts do not understand well.

In addition to the huacas near Cuzco, there were many others spread across the empire. Many high peaks were considered the homes of powerful deities by local people, and the Incas often co-opted these by placing shrines at their summits. Especially in the southern part of the empire, special shrines including human sacrifices of children and adults, were located at the summits of the highest mountains. Oracles were also important parts of the Inca and pre-Inca religions of the Andes. There were four major oracles, including one near Cuzco, where people could go to get advice. The Oracle of Pachacamac, located near modern Lima, was an ancient one, dating at least to CE 500. The Incas took control of it, and allowed it to continue as an oracle, but built their own sun temple and other structures nearby.

Rituals Great and Small

Rituals were extremely common in Inca life, and could involve something as simple as burning some coca leaves or as complicated as sacrificing a child after ascending a mountain peak above 6000 m. Rituals were conducted to assure that deities were pleased or to ward off malevolent spirits. Some rituals were daily events, like the offering of llamas and cloth to Inti every morning at the Coricancha, while others were only conducted at special occasions, like the investiture of a new king. All rituals involved some kinds of sacrifice, though the great majority were either llamas or guinea pigs. Food, ‘chicha’, or corn beer, and coca were also used, and fine cloth, seashells, gold and silver could be used as well. The ceremony defined the material to be sacrificed.

There was a full calendar of ceremonies marking out the Inca year, although there were two major festivals: ‘Capac Raymi’ in December and ‘Inti Raymi’ in June. These fell on the summer and winter solstices, respectively. Both involved several days’ festivities and ceremonies, including male puberty rites during Capac Raymi, and great displays of the present and past rulers (in the latter case, their mummies) during Inti Raymi. Large quantities of llamas, chicha and coca were sacrificed to assure the successful completion of the rituals.

One of the most important rituals was called the ‘Capac hucha’, a ritual conducted in Cuzco, but then in every part of the realm, to glorify the Inca gods. Children of about ten years of age were summoned from villages all over the empire to Cuzco, where they were dressed in the finest clothes and paired as if they were husband and wife. They were paraded through the streets from the Coricancha, past the royalty, both living and dead, and to one of the main plazas in town. Some of the children were sacrificed to Wiracocha and Inti, then to other gods and huacas in the vicinity of Cuzco. Priests then took other children and items throughout the empire, making subsequent sacrifices along the way. Particular attention was given to the powerful huacas of high mountains, as mentioned above.

Technology

The Incas are probably best known for their extraordinary stonework, where rocks weighing many tons were fitted together very tightly. Such stonework was exceptional, but no less impressive were other aspects of their technological achievements, such as their agricultural and irrigation systems.

High-quality Inca stonework was restricted to the most important buildings in the empire, and served to both emphasize the functions of such structures and the importance of the Inca system that constructed them. Huiinuco Pampa is a good example of this, as the majority of the buildings are of fieldstone and no great effort was put into their construction, but at the main entry buildings and the royal residence are found, the fitted stones and architectural embellishments, such as carved pumas, to impress the person entering them of their importance. The Coricancha in Cuzco has some of the best stonework in the empire, as befits its importance in Inca ideology, and many of the residences of the kings and their panacas also were of finely dressed stone. The foundations of many of these still can be seen in Cuzco, where they continue to stand, despite five hundred years of seismic activity, a tribute to the skills of Inca engineers.

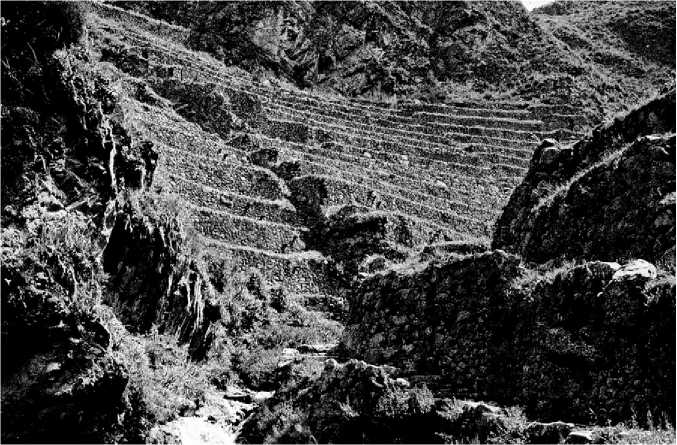

Inca agricultural systems are equally impressive. Everywhere the Inca went, they constructed or reconstructed agricultural terraces to maximize productivity (Figure 3). Systems were designed to distribute water from canals many kilometers long that came down from springs or glacial melt water higher up and then flowed down feeder canals to the systems. Sometimes reservoirs were built to store water into the dry season. These systems, like the buildings just described, continue to function to the present day.

Figure 3 Inca agricultural system at Pisac. Note projecting rocks used as steps from one terrace to another. Photo by author.

The Spanish Conquest

To understand how a group of 168 Spaniards could bring down the Inca empire, it is necessary to briefly discuss the events leading up to their appearance. With the death of Wayna Qhapaq and his heir from a European disease, the empire was left with no king. Two main rivals soon emerged, Washkar, a son who lived in Cuzco, and Atawalpa, a son by a different mother who lived in Ecuador. Washkar sent armies north to Ecuador to defeat Atawalpa, but the latter’s armies were much better seasoned, having spent many years in wars of expansion against local groups. The armies of Atawalpa defeated the forces of Washkar repeatedly, as the latter retreated down the spine of the Andes toward Cuzco. In a final series of battles fought outside Cuzco, Atawalpa’s generals decisively defeated Washkar and took him prisoner. In a grisly display of retribution, nearly all of Washkar’s kin were killed, and Washkar himself was brought north to face Atawalpa, who was now coming south to take control of the empire. The year was 1532.

As Atawalpa was resting in Cajamarca, in northern Peru, word came to him that the Spaniards had arrived and were killing and robbing the northern coastal provinces. He sent a contingent of forces under a loyal general to bring them to Cajamarca. He agreed to meet them in the main plaza of the town, a place where such meetings of important leaders would typically occur, but also a location that was perfect for an ambush. There were few entry or exit streets from the plaza, and the callancas on the sides were well suited to hiding soldiers and horsemen. When Atawalpa and several thousand of his personal guard arrived, they were met by a priest, who offered Atawalpa a book of prayers. When Atawalpa threw the book down and rose from his litter, Pizarro gave the order to attack. In the ensuing carnage, most of the Inca warriors were killed, and Atawalpa was captured. Not a single Spaniard died.

Atawalpa agreed to fill a room half-full of gold and twice fill it with silver for his ransom, an offer the Spaniards could not refuse. As the months passed, reinforcements arrived from Panama, and the Spaniards made exploratory trips to the coast. However, after the ransom was paid and melted down, it became apparent that something had to be done about the Inca king. Pizarro ordered Atawalpa gar-roted, and buried unceremoniously. He placed a son of Washkar on the throne and began to travel to Cuzco. After both victories and defeats, Pizarro and his troops entered Cuzco unchallenged, exactly a year after they had arrived in Cajamarca.

See also: Americas, South: Inca Ethnohistory; Northern South America; Southern Cone.

World History

World History