For decades, scientists thought that the New World was first populated by migrants from Asia who wandered down the center of the hemisphere about 11 500 years ago. This conventional view of the first Americans dates to the early 1930s, when stone projectile points that were nearly identical were found at archeological sites across the American Southwest and the Great Plains. They hinted at a single human migration and cultural tradition that scientists labeled Clovis, after an 11200-year-old site near Clovis, New Mexico. Because no older sites were known to exist at that time in the Americas, archeologists thought that the Clovis people were the first to enter. These first people presumably walked across dry land, the Bering Land bridge, that connected modern Russia and Alaska at the end of the Ice Age, when sea levels were hundreds of feet lower than they are today. From there the earliest Americans would have traveled south through an ice-free corridor that some geologists believe existed in what are now the Yukon and Mackenzie river valleys, then along the eastern flank of the Canadian Rockies to the continental United States and on to Latin America.

Much rethinking about the peopling of the Americas has taken place in recent years as a result of new discoveries in archaeology, historical linguistics, genetics, and palaeoanthropology. Several archaeological sites in both North America and South America have much potential to document earlier traces of human occupation. The eastern woodlands

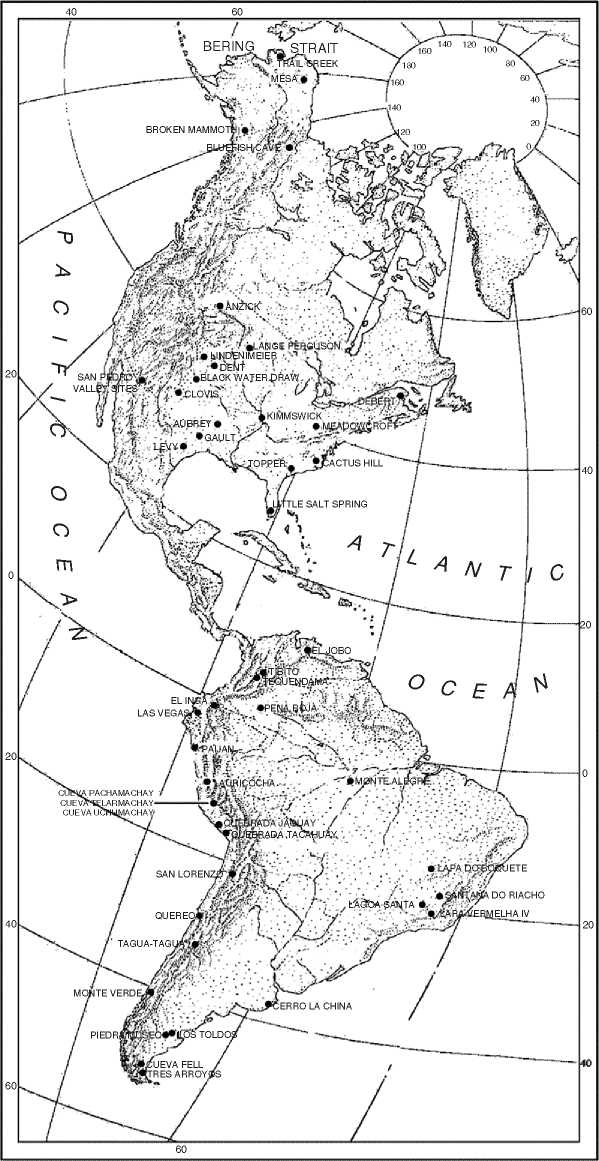

Figure 1 Map locating sites discussed in the text.

Of the United States in particular has yielded more convincing evidence of sites ancestral to the widely documented 11500-year-old Clovis culture, which is best known for its fluted or channeled projectile point and big-game hunting tradition. For instance, Meadowcroft Shelter in Pennsylvania, Cactus Hill in

Virginia, Topper Site in South Carolina, Little Salt Springs in Florida, and others suggest that people who were both hunters and gatherers may have lived in those areas as far back as 16 000 to 13 000 years ago (Figure 1). These possibilities are supportive of the 12 500-year occupation at Monte Verde and slightly later sites in South America, because if people first came into the Americas across the Bering Land bridge, we would expect earlier dates in North America. It also is likely that multiple early migrations took place and people moved along the edge of the ice sheets and coastlines from Siberia to Chile and from northern Europe into eastern North America. There also is discussion of possible influences, albeit presently very remote due to scarce evidence, from Africa and even Australia. Some palaeoanthropologists even believe that the oldest human skeletal material from Brazil more strongly affiliates with ancient Africans and Australians than with modern Asians and Native Americans. This hints at the presence of non-Mongoloid as well as Mongoloid populations in the Americas.

Linguists and geneticists also postulate earlier migrations. Some linguists believe that a high diversity of languages among Native Americans could only have developed from an earlier human presence in the New World, perhaps as old as 20 000-30 000 years ago. Several geneticists present the same argument derived from gene diversity. Based on comparisons between certain genetic signatures shared by modern Native Americans and modern Siberians, it has been estimated that people from Siberia entered the New World at least 25 000 years ago. It also is likely that there were multiple migrations into the Americas, as suggested by several genetic studies. Specifically, geneticists have focused on two types of evidence extracted from the cells of modern Native Americans: mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down only through the mother to both son and daughter; and the Y chromosome, which is transmitted only from father to son. So far, the genetic evidence sends mixed signals about the number of migrations. Some scientists believe in a single migration; others postulate multiple ones.

These new discoveries and ideas are not without their critics. Advent Clovis proponents who staunchly defend the Clovis-first theory still hold to the notion that the first Americans were mainly big-game hunters who entered the Americas from Siberia no earlier than 11 500 years ago. This theory has been dismissed and replaced by a pre-Clovis model in recent years, which believes that multiple migrations occurred long before 12 000 years ago by different populations equipped with a wide variety of technologies and subsisting on a broad spectrum of plants and animals and that pre-Clovis people gave birth to Clovis people. Yet Clovis proponents believe that notions of a pre-Clovis are based on questionable radiocarbon dates, human-made artifacts, geological context of sites, and interpretations of the evidence. Although these criticisms are often constructive and encourage a more rigorous scientific approach to the study of the first Americans, they are often based on anecdotal tales and little scientific evidence.

Despite continuing debates over the first peopling of the Americas and the ambiguity and paucity of some evidence, three issues are becoming clearer. Although the Clovis culture is the most widely distributed early record in North America and accounts for a major portion of the first chapter of human history in the north, it fails to explain early cultural and biological diversity in all of the Western Hemisphere, especially in South America. Second, Northern Hemisphere agendas about the peopling of the New World, which were developed in the historically better investigated regions of North America, have created unrealistic expectations or preconceptions about the significance of cultural developments in Central and South America. Despite the likely migration of early people from the north to the south, the archeological records of each continent must be viewed in their own terms and not be judged by preconceived notions often based on meager evidence or over-extended interpretations. Third, regardless of the quality of evidence, the first American populations seemed to have been a melting pot for a long time and possibly had their physical, genetic, and cultural roots in different areas at different times.

It is certain that the first migrants into the Americas adapted to many different environments quickly, creating a mosaic of contemporary different types of hunters and gatherers (such as big-game hunters, general foragers who hunted and gathered plant foods, coastal fishermen) immediately after they entered new environments. Further, a key issue is not so much rapid migration but rapid social and economic change and a steep ‘learning curve’ across newly encountered environments - that is, the adaptation of technological, socioeconomic, and cognitive processes from one generation to another. As the different archaeological records of South America and parts of the eastern United States suggest, this was not a single unitary process, but many. While hunter and gatherer groups were settling into one new environment, others were probably just moving into neighboring ones for the first time. Others probably stayed for longer periods in more economically productive environments. All of these processes must have begun sometime before 12 000 years ago in order to produce the types of technological and economic diversity reflected in the archeological record by 11000 years ago. The record left behind by these processes is characterized by variable site sizes, locations, functions, occupations, and artifacts that clearly reflect different adaptations to different environments.

World History

World History