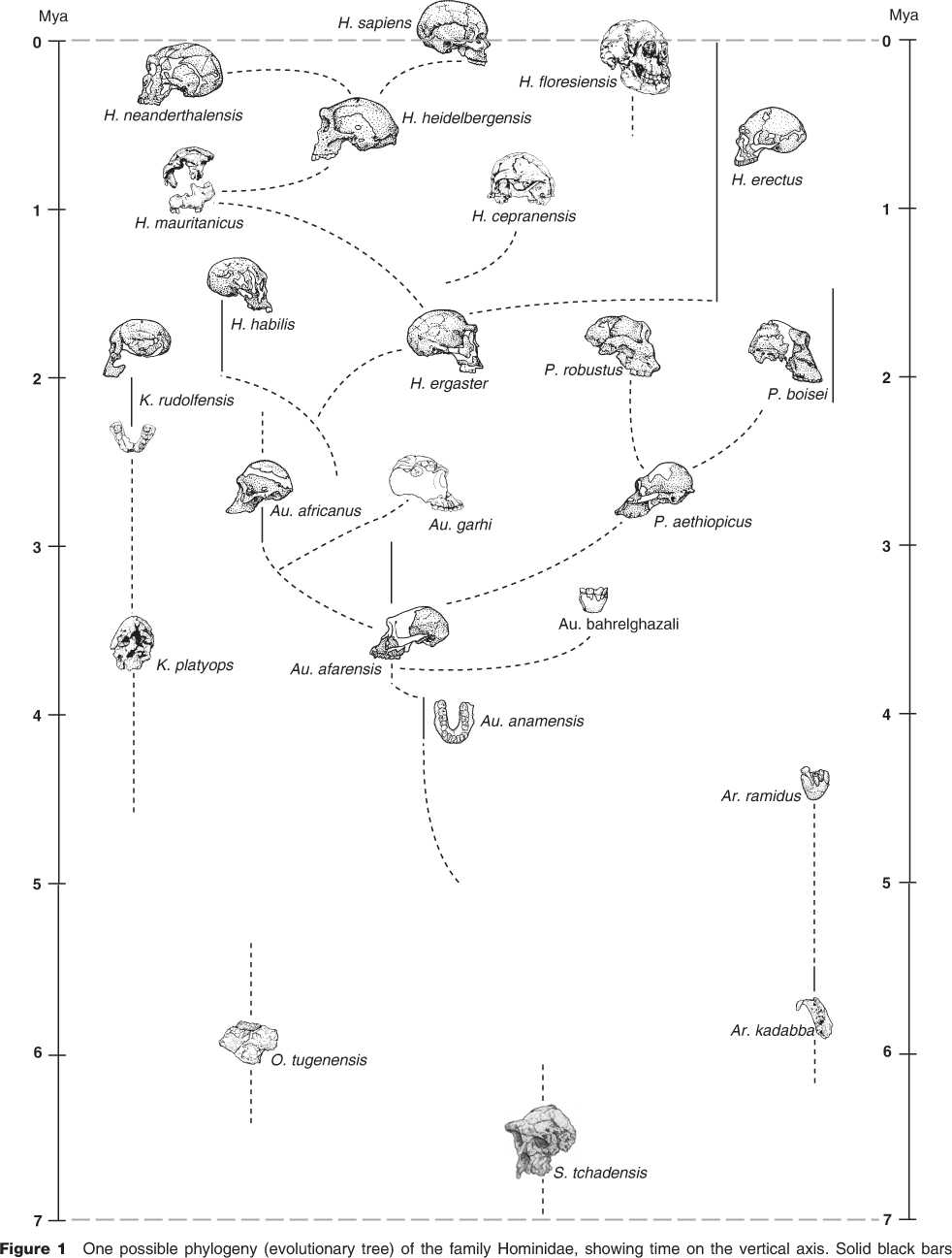

H. sapiens is today the only hominid on Earth (see Modern Humans, Emergence of). In the past this selfevident fact encouraged the view that our species is the culmination of a single progressively evolving lineage. However, extensive additions to the hominid fossil record over the past half-century or so have made it increasingly clear that, in contrast, the homi-nid story was one of evolutionary diversity from the very start (see Figure 1). Both the fossil record and molecular genetic analyses of human beings and their closest living relatives point to an origin of the homi-nid family in the period between about 7 and 8 million years (Myr) ago. This was a time in which climatic and topographic changes in Africa (where Hominidae originated) were beginning to fragment that continent’s formerly monolithic forests and to create new woodland and eventually grassland environments. There are many variants on the precise scenario, but it is generally agreed that the arboreal hominid precursor, a member of the hominoid group that also included the ancestor of today’s great apes, was forced to take up at least a semi-terrestrial existence by the shrinking of its ancestral habitat. Once on the ground this ancestor, unlike the precursor of today’s quadrupedal ‘knuckle-walking’ apes, adopted a bipedal style of locomotion. There has been extensive debate over what the ‘critical advantage’ of twolegged locomotion might have been to the hominid ancestor. Among many other suggestions are more efficient terrestrial locomotion, better shedding of the sun’s heat in the open away from the trees, freeing up the hands to carry and manipulate objects, and seeing dangers farther away over tall grass. Most plausibly, though, the hominid ancestor was most comfortable walking upright over the ground because it already favored holding its trunk erect when moving in the trees. Once it had adopted this way of getting around in the open, all of the associated advantages - and disadvantages - followed.

The notion that terrestrial uprightness was the key to hominid identity has been strengthened by fossil discoveries in eastern Africa that date to between about 7 and 4 Myr ago. Three genera of early homi-nids - Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, and Ardipithecus - have been described from this period. All of them are pretty fragmentary, but each has been described as a biped, even if on less-than-ideal evidence. They make up a rather heterogeneous assemblage, but if they were all upright hominids - rather than indicating, for example, that a variety of different hominoids experimented with bipedalism on the ground in response to similar environmental pressures - they provide eloquent support for the idea that, from the very beginning, Hominidae has typically shown an evolutionary pattern involving experimentation with the many ways that there evidently are to be a hominid.

The genus Australopithecus - first represented in northern Kenya by a species (A. anamensis) that shows definitive signs of upright bipedalism at over

Indicate documented time ranges; dotted lines indicate possible relationships, many of them highly speculative. ©2008 Dr. Ian Tattersall. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

4 Myr ago - is the best known of the early hominids. Its most famous representative is the fossil popularly known as Lucy, a partial skeleton of the species A. afarensis from 3.2-Myr-old deposits at Hadar in Ethiopia. Lucy and similar fossils are short-statured (females were not much over 3 ft tall, males not much over 4 ft), and retained many features that would have aided climbing in the trees (narrow shoulders, long arms relative to legs, long and somewhat curved hands) but show structures of the pelvis and leg that clearly indicate upright posture and locomotion. Although their dentitions have features, such as reduced canine teeth, that recall later hominids rather than apes, their skulls are very ape-like in structure, with large, protruding faces in front of tiny braincases that contained ape-sized brains with volumes no more than about a third of the modern human average. Indeed, many palaeoanthropologists like to refer to these archaic hominids as functionally ‘bipedal apes’. Fossils usually allocated to Australopithecus species are found in eastern and southern African sites (and one in Chad, in central-west Africa) that are dated to beween about 4 and 2 Myr ago. Most sediments containing them appear to have been laid down in forest-edge or woodland contexts, to which such creatures appear to have been largely confined, though occasionally there is evidence of conditions ranging from closed forest to grassland. By about 2 Myr ago, hominids of this kind had largely disappeared, with the exception of a ‘robust’ group, allocated to the genus Paranthropus, which lingered until about 1.4 Myr ago.

World History

World History