A great deal of archaeological research has been done on the sites and sequences in the various segments of the Ganga plain. This section provides a broad overview of the geographical distribution of the sites, dates, and associated artifacts from the Palaeolithic till the early historic period.

Upper Ganga Valley: Palaeolithic Presence

The Gangetic alluvium is fringed by hills and plateaux where Palaeolithic sites and long stratigraphic sequences are fairly common. The Ganga valley, however, has only one documented Palaeolithic site. This is Kalpi which lies on the right bank of the Yamuna river, in the southern segment of the upper Ganga plain.

There is nothing specifically noteworthy about the flora or fauna of Kalpi. Its importance is locational; the town of Kalpi guarded a main crossing of the Yamuna and was the starting point for expeditions from the valley section towards the north into central India and the Deccan. The lithological succession recorded in the Kalpi section of the Yamuna river is composed of three units or events which reveal a changing Palaeo-environment. Event I (76 + 11 ka to 69 +13 ka) was marked by a moderate to dry climate. It does not contain any humanly modified material, although the calcrete conglomerate at the contact of Events I and II contains quartzite pebbles with broken faces and worked-bone artifacts. The sediments of Event II (mid-point dated to 45 + 9 ka) underline humid conditions. They have yielded rich vertebrate fossils - an elephant tusk and its shoulder blade, molars of Equus, Bovids, Bos, elephant, hippopotamus, and skeletal remains of crocodiles and turtles. Several specimens of human femur have been retrieved and humanly modified bone pieces - with flake scars and sickle-shaped edges, and a bone splinter with black patina and three parallel lines - which are Event III sediments (basal section date 43 + 7ka) reveal that, towards the upper part, the climate had become increasingly dry. The Event II lithic and bone industry seems to be Middle Palaeolithic; pebble tools comprise 79.4 percent of the total lithic assemblage.

Similar fossil-rich horizons have also been recorded at Phaphamau in the Allahabad area, in the cliff section of the Ganga river near Banaras, and in a well section of a bridge near Bhagalpur in Bihar. These horizons, however, did not yield human artifacts. Kalpi, for the first time, has revealed Palaeolithic artifacts in association with such fossils, and has added a new dimension to the distribution of Palaeolithic sites in northern India.

Specialized Mesolithic Hunter-Gatherers

Mesolithic clusters in and around the Ganga plains are mainly in the Allahabad-Banaras zone. There are a large number of contemporaneous open air and rock shelter occurrences on the eastern fringe of the Kaimurs/Vindhyas, but since these are not in the valley itself, they cannot be treated as part of the Ganga sequence. In the Ganga alluvium, there are around 200 open-air sites, generally small and marked by a handful of microliths. There are, however, some larger settlements - Damdama, Mahadaha, and Sarai Nahar Rai - which have provided extensive evidence of a deep-rooted Mesolithic occupation of the central Ganga alluvium. These are not temporary camp sites but settlements that were continuously inhabited.

Three separate areas have been demarcated at Mahadaha: a burial-cum-settlement area occupying the central position within the settlement, a butchering area between the settlement and the western margins of the lake where it was situated, and a lake area where excavations have revealed a significant amount of occupational debris in what was once the bottom of the lake. Several circular and oval hearths were found inside the burial-cum-settlement section; the excavated hearth yielded charred bones. The butchering area was used for butchering animals like cattle, hippopotamus, pig, turtle, and most frequently, deer. It was also used for making bone tools and ornaments. That the lake area yielded thousands of bones suggests that the debris was pushed deliberately into the lake. Damdama is located at the confluence of two branches of a drainage line called the Tambura Nala. Like Mahadaha, it has yielded various species of animals, with as many as six varieties of deer. There are plant remains from the site as well, mostly of different wild varieties, with a recent analysis also suggesting the presence of domesticated rice. Hearths, in addition to their use for cooking, were also connected with the manufacture of stone and bone tools.

Extensive evidence of burials containing skeletons of males, females, and children has been revealed from within settlements. Those at Sarai Nahar Rai are in the form of shallow, oblong pits with tapering sides, with microliths as grave goods. A microlithic arrowhead was also found inside the rib bones of a skeleton, indicating in this case, the cause of death of the individual. Osteoarthritis was the major pathological feature of these skeletons; stress markers indicate activities like spear-throwing, stone-throwing, and using sling shots. The Mahadaha graves are shallow and elliptical and the grave goods fairly extensive. These comprise arrowheads, animal bones, pieces of hematite, necklaces, ear ornaments, and bone rings. There are two double burials, a male and female together, and a young adult male and an adult male in another. There are many more double burials at Damdama, as many as six, of which five contained a male and female together. The sixth grave provided skeletal remains of two males and a female.

Incidentally, year-long burial and habitation has been assumed on the basis of the occurrence of bandicoot rats at Mahadaha and Damdama, and on the basis of the study of the orientations of these graves in relation to azimuth.

The Ganga Mesolithic, as has been pointed out, is geographically concentrated around meander lakes and streams which were formed around 8000 and 6000 BP. It is likely that large-scale Mesolithic habitations coincided with the formation of these lakes. The C-14 date from Mahadaha and the TL date from Damdama of the sixth and fifth millennium BC support this hypothesis. At the same time, the beginnings of the Mesolithic can go as far back as the beginning of the Holocene. Damdama, for instance, is situated on a rivulet which must have been a flowing channel at the time of occupation. Such channels are known to have ceased by 8000 BP. If this is correct, then Damdama had to be occupied much before this date.

The dates from the central Ganga plain have important implications in relation to the early evidence of agriculture from the same geographical zone. This evidence will be discussed in detail below. At this point, it may be underlined that there are indications that it is not a stagewise evolution that is witnessed here with incipient agriculturists replacing hunter-gatherers. On the contrary, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and the first agricultural communities were coexisting in this tract, with the former marked by a degree of sedentism and an intensive exploitation of plants that is usually associated with groups practicing agriculture.

Early Agriculture

An early transition from food gathering to food production has recently been established in the middle Ganga plains, around the Sarayu valley of Uttar Pradesh. This concerns the early cultivation of rice but before spelling out the nature of the evidence, related issues concerning the beginning of food production in the subcontinent in general and the Vindhyan edge of the Sarayu and its contiguous alluvial plains in particular, need to be clarified.

South Asia saw the emergence and evolution of agriculture and animal domestication in multiple zones. The earliest center for the cultivation of wheat and barley (and the independent domestication of the latter) from c. eighth millennium BC onwards, is at Mehrgarh in Baluchistan (see Asia, South: Baluchistan and the Borderlands). The possibility of an early transition from hunting-gathering cultures to agriculture and pastoralism in certain other areas may also be considered, although the evidence is ambiguous. For instance, in the Ladakh region, the Neolithic site of Giak is as early as the sixth millennium BC (calibrated radiocarbon date), although another site of the same cultural complex has yielded a c. 1000 BC date. Another such case is that of Rajasthan, where several salt lakes have yielded a ‘cerelia’ type of pollen in a c. 7000 BC context, along with comminuted charcoal pieces. This is apparently indicative of forest clearance and the beginning of some sort of agriculture. However, to archaeologically confirm the lake evidence, food-producing cultures of similar antiquity will have to be discovered in Rajasthan.

In the case of the Ganga valley, it was the peninsular edge of the central plains, marked by the sites of Koldihwa and Kunjhun which showed early-Neolithic stratums representing rice-producing communities. There were problems, though, concerning the chronology of cultivation since, of the nine radiocarbon dates of Koldihwa, only three go back to the seventh and sixth millennia BC. However, there is now much clearer evidence from recent excavations at Lahuradeva (Sant Nagar district) in Uttar Pradesh which, importantly, suggests that such early rice cultivation was not confined to the Vindhyan hills but extended into the Gangetic alluvium.

The microcharcoal recovered from the 2.8 m thick sediment succession of the lake on the edge of which Lohuradeva’s mound is situated, suggests fire caused by slash-and-burn cultivation in the area from 10 000 BP. The lowest archaeological deposits of the site have yielded domesticated rice a little later; these are dated to 8259 BP (calibrated). This occurs in the lowest level in association with both wild rice (Oryza rupifogon) and foxtail millet (Setaria sp.). Husk marks of rice are also embedded in the core of a number of potsherds in this earliest phase of cultural occupation there - IA-which is marked by coarse red ware and black-and-red ware, with cord impressions on its exterior.

The beginning of food production in the Indian subcontinent is a multihued tapestry in which the early presence of rice in the central Ganga plains forms an important strand, underlining that this zone was part of an early nuclear center of agriculture.

Advanced Agriculturists

The first stage of sustained village growth in and across the Ganga valley is chronologically later than the beginning of agriculture witnessed in its central segment. Generally speaking, there is widespread growth of agricultural communities in the upper and central Ganga plains from the late third millennium-early second millennium BC, while in the lower Ganga valley, the radiocarbon dates are squarely in the second millennium BC. The term used to describe these cultures is ‘Neolithic - Chalcolithic’. This is not a particularly logical classificatory label but has been extensively used in Indian archaeological literature to describe early village cultures in areas that are outside the geographical ambit of the Harappan civilization (see Asia, South: Indus Civilization). The term includes pure Neolithic communities with a predominantly stone technological component and those groups that are ‘Chalcolithic’ , in the sense that they use both stone and copper.

Additionally, early iron-using advanced agricultural communities and groups are also discussed here. In many instances, the use of iron entered into the productive system without producing any major changes in those early contexts. In eastern India, for example, the Chalcolithic black-and-red ware culture became iron-using towards the end of the second millennium BC. Bahiri, Mangalkot, and Pandu Rajar Dhibi in Bengal are examples of this and, as we know, the birth of cities in that zone was several centuries later. Moreover, there is remarkable continuity in terms of crop patterns and settlement locales. Therefore, it is logical to discuss Neolithic - Chalcolithic and ironusing agricultural societies as part of the same protohistoric agricultural horizon. The impact of the use of iron on the Gangetic valley was slow and steady; it does not seem to have had consequences that are visible in the archaeological record. On the contrary, there is a gap of more than a thousand years between the appearance of iron in this region and the emergence of urban horizons.

Multiple regionally distinctive archaeological cultures dominate the Ganga valley; their presence can only be mentioned in passing here. In Bengal, a primarily rice-cultivating horizon of black-and-red ware sites - roughly 70 Chalcolithic and iron age black-and-red ware sites - spread across valleys west of the Bhagirathi. The river valleys are several, from Dwaraka to the Kasai as one moves north to south, where the rivers flow from the west to the east into the Bhagirathi. Moving along the Ganga into Bihar, in its southern segment which is known to have a long prehistoric segment, no early Neolithic or farming community is known. On the other hand, in the alluvial plains of northern Bihar there are several such sites - Chirand, Chechar-Kutubpur, Senuar, Maner, and Taradih are some of the important ones. These are riverbank sites with Chirand, Maner, and Chechar-Kutubpur on the Ganga itself. Their cultural deposits indicate a secure, long presence. Chirand is an example of this; its Neolithic stratum (Period 1) is 3.5 m thick. It is marked by Neolithic axes, bone and antler implements, along with a rich microlithic industry. The ornaments are equally diverse - in bone, ivory, agate, carnelian, jasper, steatite, and faience. The farming pattern is a broad-based one with the remains of crops like rice, wheat, barley, and lentil while the animal remains include domesticated cattle as also wild animals like elephant and rhinoceros. Most importantly, this represents pre-metallic agricultural villages that largely thrived in the late third millennium BC, possibly continuing into the first century of the second millennium BC. Subsequently, they were to become metal-using cultures marked by black-and-red pottery.

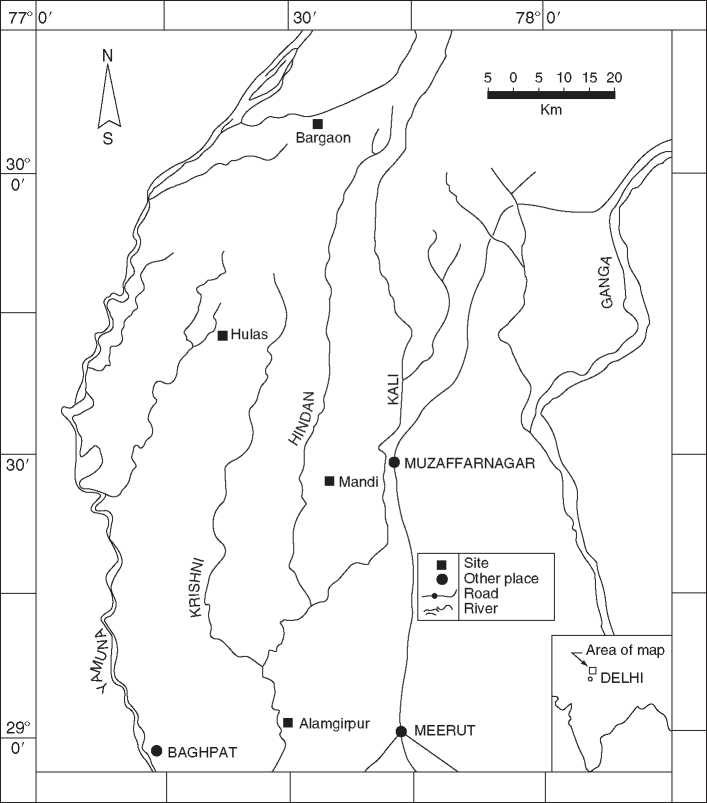

Towards Uttar Pradesh, in its eastern segment, Lohuradeva which marked, as we saw, a very early rice-cultivating site, in this phase (Period 1B, late 3rd and early 2nd millennia BC) saw a profuse occurrence of black-slipped ware, which has been described as the hallmark of the developed farming phase of the central Ganga plains. In the middle of the second millennium BC, the southern segment of this region saw the emergence of a long archaeological sequence at places like Imlidih, Narhan, and Sohgaura marked by pre-Narhan, Narhan, and black-and-red ware horizons. Basically, what one witnesses is the consolidation of a broad-based plant regime which includes rice, barley, varieties of wheat and millet, and also other cultivars like lentil and gram. Further west, in the upper Ganga valley and the Yamuna-Ganga doab, it is again late third millennium BC cultures which mark the beginning of long archaeological sequences that eventually evolved into a phase marked by urban centers (Figure 4). These cultures are: the late Harappan culture, ochre-colored pottery culture, black-and-red ware culture and the painted gray ware culture (the last two are iron-bearing horizons). The ochre-colored pottery culture is possibly a late manifestation of the same complex in the Rajasthan plain.

A clarification about the plethora of cultures that are mentioned here is necessary. These are cultures that have been named in a number of ways: the designation of ‘late Harappan’ suggests successor groups that devolved from the mature urban Harappan tradition; others are designated on the basis of the sites where they were first discovered (Narhan is an example), while a few are named after the pottery that is typical of the said culture (painted gray ware and ochre-colored pottery are some such cultures). In the case of cultures that are named after a pottery type, this does not mean that this was the only type of pottery that was used and manufactured by such a society. For example, painted gray ware that gives its name to first millennium BC Iron Age culture of the upper Gangetic plain, in most cases, constituted less than 15% of the total ceramic assemblage and coexisted with plain gray, black-and-red, black-slipped, fine red-slipped and unslipped and coarse red wares. But the reason why it has been used to designate this cultural phase is because it is its archetypal pottery. On the question of pottery cultures, a clarification about one of them - the black-and-red ware

Figure 4 Important late Harappan and ochre-colored pottery ware sites in the Yamuna-Ganga doab (after Tewari 2004).

Culture - is necessary. On the one hand, black-and-red ware gives its name to a specific culture of the upper Gangetic plains, as also to a culture in the middle and lower Gangetic plains. This does not mean that the protohistoric farming cultures that used this pottery were a homogeneous cultural entity. The shapes and designs are different as is the time range. For instance, the black-and-red ware culture of the upper Gangetic plains is an early second millennium BC phenomenon while the black-and-red ware culture of Bengal is a second-first millennia BC phenomenon.

The picture is one of great diversity made up of Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and iron-bearing farming cultures. This is a diversity which has important implications for understanding the evolution of the agricultural geography of the Ganga valley. It clearly underlines that that no one culture or one society can claim to be the harbinger or pioneer in the creation of a strong agricultural base there. The situation in the doab is qualitatively different from that in eastern

Uttar Pradesh. Again, the communities in the latter region, in their trajectory of cultural development are qualitatively different from the manner in which village cultures in Bihar evolved.

What is common to them is that, in more ways than one, they represent a kind of watershed for the advent of stable agricultural societies in their respective tracts. It is from this period onwards that long columns of archaeological cultures become visible and the fact that there are few gaps in the sequence also means that we are looking at fairly continuous occupations. One aspect that emerges clearly from the archaeology and geography of the Neolithic-Chalcolithic and Iron Age farming communities is the growth in population and the evolution of a complex settlement pattern. In the Kanpur district (Uttar Pradesh), for instance, whereas there were only nine black-and-red ware sites, the number of sites of the succeeding painted gray ware culture is 46. Moreover, there is a clear hierarchy in the settlement sizes. While as many as 38 of them can be considered as small villages, four seem to be large villages while four of them would be considered as regional centers. Generally speaking, this kind of multi-tiered settlement hierarchy with settlements that range below one hectare to a few that are around five hectares or so is considered as a reliable index of the evolution of a complex society. From this base, eventually cities and state structures would emerge.

Another key variable that one sees emerging in this period is an organized articulation of trade networks which brought various kinds of resources to the Gangetic plain. This can be clearly seen in the painted gray ware phase. The painted gray ware phase, incidentally, provided the base for the emergence of urban centers in the upper Gangetic plains. An important site which reveals the kind of raw materials that were used in this period is Atranji-khera. Here, there are agate, carnelian, quartz, and marble beads; also objects of ordinary stone like pestles and whetstones of red sandstone and limestone; a shell fragment; almost two dozen copper objects; as many as 135 iron objects including iron slag (which shows local metalcrafting/smelting); and chir pine (Pinus Roxburghii) . None of these - stone, metals, pinewood - is locally available. It is likely that there was already a class of traders that was procuring such raw materials so that local manufacture could be sustained.

Territorial States and Urban Centers

Till now, this essay has used modern geographical and political designations to describe the different units and subunits that make up the Gangetic valley. What, though, were the ancient names of the geopolitical orbits in this vast tract, and how can they be delineated? This is essential for understanding the political geography of the Ganga valley.

Ancient territorial designations are mentioned in Indian literary sources ranging from later Vedic to Buddhist literature. Their presence coincides with the process of early historic growth which can be dated from c. 700 BC onwards. In the archaeological record, the marker of the advent of the historical period in the Gangetic plains is the Northern Black Polished Ware which appears after the painted gray ware in the upper Ganga valley and after the black-and-red ware in the middle Ganga valley. Early historic city sites have been identified across the valley as have been the communication lines and networks that connected them with each other and the valley as a whole.

In the first phase of state formation in India (c. sixth century BC), multiple states called ‘janapadas’ can be identified in this valley. As many as 16 early states are mentioned in Buddhist sources, an overwhelming number of these situated in the Ganga plain. These are: Kasi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajj'i/Vrij'j'i, Malla, Vamsa/Vatsa, Kuru, and Panchala. While sacred geography cannot be explored here, it is worth remembering that this is also where religions like Buddhism and Jainism established early roots and in the same time period, under their founders Gautama Buddha and Vardhamana Mahavira respectively. Substantial support for them came from the urban centers of the Ganga valley and the mercantile prosperity that marked them.

In all these polities, urban centers have been identified, several of which were also political capitals of their respective states. Kuru and Panchala were firmly entrenched in the upper Ganga plain marked by cities like Indraprastha, Hastinapura, and Ahichchatra. The city of Kasi is identified with the area of modern Varanasi on the left bank of the Ganga and would have been situated between the Varuna and Asi streams. The Kasi region extended from the Ganga towards the east up to the Ghaghra, and on the north up to Jaunpur and (part of) Sultanpur. Kosala’s successive capital cities were Ayodhya/Saketa and Sravasti., while the state covered both banks of the Ghaghra/Saryu river. Malla janapada lay to the west of the Gandak river, with its capital in Kusinara, and included the modern Padrauna and Deoria areas as well. The territory of Vatsa was focused around cities like its capital Kausambi on the right bank of the Yamuna, ancient Prayag or Jhusi on the left bank of the Ganga, and Bhita and Kara on the banks of the Yamuna and Ganga respectively. Magadha radiated in a linear fashion between the Kiul and Karamanasa rivers which separate modern Bihar from Uttar Pradesh as far as the point where the Hazaribagh area begins. Its earlier capital was Rajagriha and later Pataliputra. Anga janapada lay spread between Rajmahal in the south and Kiul/ Lakhisarai in the north with Champa on the northern outskirts of Bhagalpur as its capital. Finally, a conglomeration of republican janapadas, known as the Vajji or Lichchhavi confederacy, dominated the modern plain of north Bihar with its capital at Vaisali.

From a geopolitical perspective, the primary focus of early state formation was the middle Gangetic valley. It was a middle Gangetic state, that of Magadha, which eventually become the nucleus of an empire under the Nanda dynasty. Its first king Mahapadmananda (c. 355 BC) ruled virtually all of north India up to the Yamuna-Ganga doab on the one hand, and the Deccan on the other (see Asia, South: India, Deccan and Central Plateau). Again, under the Mauryan dynasty (c. 324-187BC), with their base in Magadha, a pan-Indian empire extending from south Afghanistan to the Chittagong coast and from Kashmir to peninsular India was established. The subcontinental domination of an empire with a Gangetic valley power base did not survive the end of the Mauryan dynasty. Subsequently, the Sunga dynastic orbit shrank back to the earlier orbit, from Magadha to central India. In the early centuries AD, the Gangetic valley was brought within the empire of the Kushanas, as they extended their Oxus-Indus base. By the beginning of the fourth century AD, the focus shifted back to a middle Gangetic power base, with the advent of the Gupta dynasty that was based in Magadha (Figure 5 ).

Political units and urban centers also extended beyond the upper and middle Ganga valley. The ancient geographical units there ranged from Samatata and Pundravarddhana in the trans-Meghna area of Bangladesh and the Barind northern tracts respectively to Vanga and Suhma in the deltaic coastal tracts of Bangladesh and Bengal. In the estuarine and coastal belt, there were around ten urban sites; their general configuration was largely riverine. Chandraketugarh appears to be the largest among them, a fortified settlement measuring one mile square, with occupational remains outside it as well. Going back to the Mauryan period, the most spectacular antiquities from this city are its thousands of terracottas marked by erotic, religious, and narrative themes. Chandraketugarh’s location in relation to a river is not obvious, although the general area itself is crisscrossed by numerous drainage channels. Among the drainage lines, it was along the old channel of the Ganga, known as Adi Ganga or the original Ganga, that settlements dating to the Mauryan period were clustered (Figure 6). The sites are mainly riverine. Boral, near the Adi Ganga in the southern section of the Calcutta area, yielded antiquities from the late centuries BC till the end of the first millennium AD.

It is at Gangasagar that the Ganga pours into the sea, with such force that her muddy waters are distinguishable for six hundred kilometers into the Bay of Bengal. Naturally, this area has an ancient and modern significance. Where the original Ganga joined the sea, is Mandirtala (on the Sagar island) which has yielded antiquities that go back to early centuries AD. Again, there is a modern temple at or near the spot where the Ganga was supposed to have entered the sea where, annually on the day of winter solstice, pilgrims from all over India gather to worship. This temple has had to be shifted from time to time in response to the encroachment by the sea but the sanctity attached to this place of confluence is abiding.

World History

World History