Three routes from Subarctic Canada to the American Southwest have been proposed. The Intermountain one is the least promising because the Hare, Bear Lake, Dogrib, Yellowknife and Chipewyan are not mountain Dene and there is little supporting data. A Foothills route has been suggested because some arrowheads are supposedly similar along Alberta’s foothill sites, but others disagree on their specific traits. Furthermore, notched quartzite cobble axes

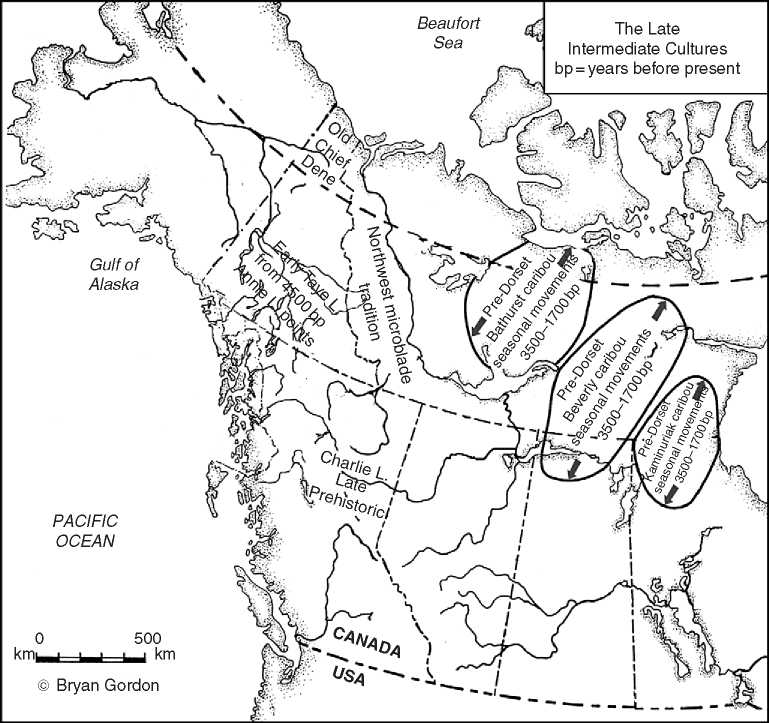

Figure 9 The late intermediate cultures, including seasonal movements of Barrenland hunters and caribou herds. © 2008 Bryan Gordon. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

And adzes like those of the northern Yukon Dene are present in Saskatchewan sites, but are absent in Alberta. These and unproven arrowhead similarities mitigate against a Foothills route. The most plausible route for southern Navajo-Apache migration is via the open Plains (Figure 4).

Evidence of a Plains route south appears in Late Taltheilei times, as indicated in Plains Side-Notched arrowheads mixed with Taltheilei side-notched arrowheads and other artifacts at Black Lake near Lake Athabasca. The Plains path crosses the Churchill and Saskatchewan Rivers via an archaeologically unknown area west of AD 500-1000 Laurel and AD 1250 Selkirk peoples of Manitoba, and it remains unknown if the Dene contacted them. Crude quartzite Late Taltheilei side-notched arrowheads (Figure 2b) merge into fine chert Plains Side-Notched arrowheads across Saskatchewan. This is the first suggestion of Late Taltheilei fading into the dominant Plains culture, as Taltheilei knappers honed their skills using superior Plains chert. On the North Saskatchewan River, Taltheilei is inferred to be present by Middle Plains Period ovoid and notched knives and gouges and pushplane-shaped endscrapers very like those of Late Taltheilei.

Over a millenium ago, at the northern edge of the Saskatchewan parkland and prairie, some Late Taltheilei or ancestral Chipewyan bands became more dependent on bison and less on caribou. Gradually being drawn to the seasonal movements of the bison going south to the short grass prairie of southern Saskatchewan, some bands adjusted fully to the bison’s ‘spoke-and-rim’ migrations, often ending in winter far from where they started in spring. Bison move into the short grass prairie in summer and out to the aspen parklands to the north, the foothills to the west, or the woodlands to the east in autumn. Hunters beginning their seasonal hunts may move into the short grass prairie from one direction and out another, especially after a drought. In the process, and likely being driven by drought effects on moving bison, several Chipewyan bands kept moving south, rather than north, west or east. The stable AD 9001200 Neo-Atlantic Episode grassland may have first attracted ancestral Chipewyan to the Plains, while the AD 1200-1550 Pacific Episode climatic deterioration may have hastened their move south (see Americas, North: Plains).

Supporting this hypothesis of a southern Chipew-yan movement via the archaeological record is their speech, which most clearly resembles Navajo. Navajo has the greatest retention of Chipewyan words. Minimal Chipewyan linguistic divergence puts the Navajo within the AD 800-1200 date range of Taltheilei side-notched arrowheads (Table 1). The relationship between Chipewyan and Navajo is also supported by three skeletons excavated near Colorado’s Trinidad Reservoir. They have Dene-specific first molars, suggesting the Navajo or ancestral Chipewyan were there from AD 750-1000. If so, they arrived in the southwest well after the Avonlea phase of the Northern Plains, and well before the Dismal River phase of the Central Plains, the previously accepted indicators of Dene or Athapaskan presence. They arrived well before Coronado’s 1541 notations of Apache in his journal.

The Apache, diverging similarly to Navajo from Chipewyan, moved south as a unit. The Navajo and Apache split in eastern Colorado, the Apache retaining a Plains orientation while the Navajo evolved into a new Southwest-adapted culture. Some linguists say the split was farther north based on the Chipewyan ‘t’ and ‘d’ sounds diverging and reappearing later and separately in Navaho and Apache.

Ancestral Chipewyan may be found in the American Southwest using a testable Preceramic Dene phase. To do this, one must ignore the earliest pottery of the Navajo and their five-pole hogans and ubiquitous triangular arrowheads. Instead, one should consider side-notched arrowheads and look for the remains of simple brush shelters or tipis, arrowshaft smoothers, hide abraders, bone fleshers and beamers, large retouched flakes and knives, dog transport, and the sinew-backed double-curved bow released horizontally. Drawn to the chest, this archery technique reduced accuracy, pull and range by two-thirds, but favored a hidden approach and gave the Apache-Navajo distinct military advantages when entering new areas.

There are many gaps in the prehistory of the Subarctic Dene. The Dene west and east of the Continental Divide and north and south of the 49th Parallel appear on first impression to be so different. Yet there is an underlying similarity, not just in their language and social structure, but in the fact that they were inveterate borrowers from other cultures. This has presented immense challenges to archaeologists, but, hopefully, we can make them more visible by examining their whole culture area, the largest in North America.

See also: Americas, North: American Southwest, Four Corners Region; Arctic and Circumpolar Regions; Eastern Woodlands; Plains; Rocky Mountains; New World, Peopling of.

World History

World History