Edmund Leach pointed out three food categories: edible, edible but not eaten/tabooed food, and edible but not recognized as food. These categories are culturally constructed and in some ways are physiologically arbitrary. There are a range of poisonous things that are considered delicacies. In addition, there are many edible substances in environment that people do not consume. Further, people can transgress their own rules of edibility if situations change. During low levels of food production situations, less desirable foods grown and collected are consumed. An extreme example is seen in emergency settings with the threat of starvation in the acts of cannibalism.

Food preferences have a genetic bias. Sweet is the earliest and most innate taste desire that humans share with other primates. This has been linked to a desire for ripened fruit and mother’s milk. While all people might begin their lives desiring sweet tastes. This desire for sweetness can and has been modulated culturally, as seen in the overpowering need for sugar products in the English and American diets while in France and the Middle East, sugar is less desired. Over the past 500 years sugar has become a powerful force in the creation of modern European economic (and moral) decisions. Desire for sweetness has escalated in the capitalistic commodity trade. During the development of international trade, first with sea traders and the spice trade, sugar, like pungent spices, evolved from a rare exotic into an essential commodity through the manipulation of an ‘objective’ taste, reorienting not only dietary esthetics but also state economies and political positions. Such a broad potential in food preferences invites us to think critically about the ways food reflects past societies, both in stasis and in change.

Chemistry is part of the interest in sweetness. People gravitate to some distinctive flavors to enhance their eating pleasure. In foraging societies, the most preferred tastes are fatty and sweet. These flavors are associated with well-being and confer superiority to the consumer. Strong tastes or flavors are often linked to life stages and initiation rites, where youth consume especially strong-flavored foods (chili peppers, meat, alcohol, tobacco), and either don’t have food or have too much food to imprint the initiate during the ritual. Piquant foods should be identifiable in the archaeological record, if we add characteristics like taste to our food descriptions.

Like food preferences, most taste aversions are learned. Eating something that swiftly creates nausea can strongly encode distaste for the substance that instills a food aversion throughout a lifetime. Visceral reflexes direct these aversions to specific foods, even if the foods are edible, clean, and do not generate an allergic reaction. Powerful emotive events can also participate in converting an aversion to a liking, as they reform the person into a new social position within society.

Food prohibitions are the mirror image of food selection. Most taboos (food prohibitions) are group specific. Although there are rules for what is to be eaten, by whom and when, these are less common than prohibitions of consumption by social position. Certain foods are deemed appropriate for some people but not for others, based on political, religious, moral, or social constructs. This is the basis for food taboos. Most taboos tend to be linked to conditions (like pregnancy) or activity (like planting a field) or they are dictated by religious dicta, active for the whole community. There are also food selection models that are similar to taboos, but these are oriented toward the food item themselves. These types of taboos are based on the physical qualities of the plants and animals. It is believed that, if consumed, the plant’s or animal’s physical characteristics will be transferred to the consumer and will enhance or harm the individuals.

Another important food preference and selection model revolves around scarcity, value, restricted access, and hierarchy (social or political ranking). Strong food preferences are usually applied to expensive, scarce, or highly valued foods. Rare or expensive foods are often associated with festive occasions, consumed at special occasions, like meat in the Andes or champagne in Europe. These types of foods play a part in creating varied forms of social, political, and economic differences.

Food preferences are built upon historical traditions. They are based not only on taste and texture but also on processing and cooking methods. The speed of adopting new foods is based upon accessible food processing technologies. If a new plant or animal fits into an ongoing culinary tradition, storage, cooking, or processing practices, acceptance will be rapid. When there is no precedent for processing or cooking a new foodstuff, the ingredient is less often or more slowly adopted. Historically, we have this displayed in staple crop adoption. Adding maize to a grain cuisine is an easy adoption, because the same storing, cooking, and meal activities are applied. Adding a tuber crop into a grain diet requires new storing, processing, and cooking strategies that will need to be imported or developed. This slows acceptance, as these additions are hurdles to the psyche and the daily practice of the consumer. This model is testable archaeologically, useful in the study of agricultural and cooking techniques, as well as in contact and cuisine.

Social difference is perhaps one of the most common active principles of cuisine. Foods can be desirable in one group yet abhorred in others, thus setting up a central feature in defining group boundaries. Identity differences based on differing cuisines operate between every group. Self-identity situates the individual with respect to their place in the world, creating values, beliefs, and ways to act that are acceptable and comfortable. Identity contributes to how individuals and groups perceive and construct society. Being a person within that society is reaffirmed through shared core foods, dishes, and flavors. People have strong feelings about their own cuisine and often aversions to foods of other cuisines. Cuisine boundaries have been identified in several archaeological examples where neighboring groups regularly have different plant and animal frequencies. Different flavors and dishes were probably identified with these different groups, maintaining their different identities through their foodways.

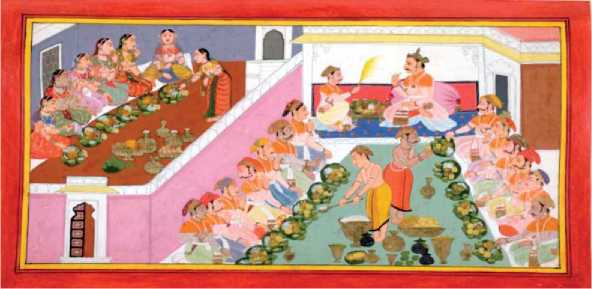

Figure 1 The gastro-politics of the feast.

There are a series of terms that are used within the sub-discipline of food archaeology: food, foodways, commensal, and gastro-politics. Food is, of course, the things that are procured and consumed, but the term can also be used in lieu of cuisines, referring to styles of cooking and eating (Figure 1). Foodways is the system of food procurement, distribution, preservation, preparation, presentation, and consumption. Many have begun to use the word commensal to mean communal eating, especially at feasts, after Dietler’s use of it in his 1996 commensal politics article. In these situations, commensality infers group eating, that is not eating alone. Originally, the word ‘commensal’ means ‘sharing a meal’ in Middle English, from Medieval Latin commnslis (com meaning ‘with’ and mnsa ‘table’). But since there are also ecological uses of this word, it causes confusion for some readers. Appadurai introduced a different term for the more political side of communal meals. He uses the term ‘gastro-politics’, a useful concept as it stresses the charged innuendoes and ulterior motives that underlie supra-family meals. This dynamic can occur at family meals as well. These political dimensions of meals indicate and construct social relations of equality, intimacy, and solidarity. They also sustain relations characterized by rank, distance, or difference.

World History

World History