Both North and South American archaeology have long shown an interest in comparing Pleistocene and Holocene social and economic strategies. Traditionally, archaeologists have treated the Late Pleistocene period as a separate historical and cultural phenomenon, not paying much attention to the fact that this was the epoch that planted the initial seeds for the social and cultural foundations of subsequent Holocene societies. Studies have contrasted mobile, nonterritorial Late Pleistocene groups who primarily hunted territorial grazers (e. g., mammoth, mastoon, bison, and paleocamelids) with more semisedentary or territorial Holocene communities whose subsistence needs were met from a combination of plants, shellfish, and large and small game. Recent studies suggest that the importance of plant foods in Late Pleistocene subsistence has been underplayed. Supporting empirical evidence for the importance of plants comes from the well-preserved site of Monte Verde (Figures 9 and 10) in the forests of southern Chile, as well as from the wide range of plant food remains known from several sites in the Eastern United States and in Brazil, Peru, and Colombia. Exploitation of plant foods may have been facilitated by the innovation of new technologies, such as digging-sticks to extract edible roots and tubers. Grinding stones for processing hard foods such as nuts and some fruits also are more commonly excavated in early sites, especially in the forested United States (Thunderbird, Gault, Dust Cave) and the forested lowlands of South America (Pena Roja, Monte Alegre, Santana do Riacho, Lapa Verhelma IV).

Figure 9 View of the wood foundations of a long tent-like structure at Monte Verde.

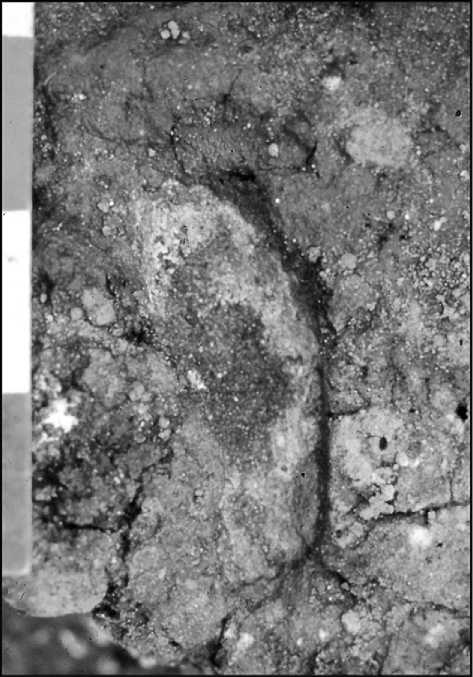

Figure 10 Human footprint preserved near the tent-like structure at Monte Verde.

In recent years, more archaeologists are beginning to examine the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene periods from a different perspective; they are considering how later social developments were predicated on the cultural diversity (mainly technology) and broad-spectrum economies of earlier hunters and gatherers. The rapid efficient adaptation of regional Late Pleistocene and subsequent Early Holocene populations to diverse environments may partially explain why some forms of incipient social and economic complexity appeared earlier in parts of Mexico and South America than in North America. For instance, squash and possibly other cultigens may have appeared as early as 10 000 to 9000 years ago at sites in Ecuador and Peru, while pottery production was established by at least 5500 years ago in parts of Colombia, Brazil, and Ecuador, human mummification by 7000 years ago in northern Chile, monumental architecture by 6500 years ago in the Lower Mississippi Valley, and by 5500 years ago in Ecuador and Peru, and so forth. What triggered these early cultural developments in diverse environments is not well understood. It might relate to advanced hunter and gatherer societies intensifying broad-spectrum diets in lush environments such as patchy forests and low coastal wetlands, in highly compacted ecotones along the flanks of the central highlands of Mexico and the Andes farther south, and in the confluences of large river systems such as the Mississippi and Amazon. In each of these areas there is growing archaeological evidence to suggest that different social and historical processes were acting in terminal Pleistocene and Early Holocene times to form early food producing and more territorial, if not permanently settled, groups in some areas.

Social and economic intensification are seen to be causally interlinked in parts of the Eastern United States, Mexico, and South America. Increased manipulation or control of the environment, combined with improvements in technologies designed to extract more food resources, probably led to increases in human population size and density and to the formation of new territorial and alliance systems between different groups, especially along the interior rivers of the eastern forests of the United States and along the desert coasts and adjacent western slopes of the Andes in Peru and north Chile where culturally complex societies developed in the Early to Middle Holocene period (9000-7000 years ago). The appearance of new technologies (facilities for storing and preserving food, grinding stones, permanent domestic structures) during this period in these regions suggests increased food productivity and more localized territorialism.

America north of Mexico and high-latitude regions of the extreme Southern Hemisphere presently do not show the same early complexity of plant domestication, technological diversity, and population density that characterizes many highland and lowland areas in Central and South America. (An exception is early mound cultures dating as far back as 7000 to 6000 years ago along parts of the lower Mississippi River, albeit cultivars are absent.) The reason is surely not that northern and extreme southern populations were cognitively unable to undertake the kinds of developments observed in the archeological records of more complex intervening populations, but that they chose to deploy them rarely or infrequently. The former populations may not have been, as the anthropologist Martin Wobst has noted for Europe and other regions of the world where less complex hunters and gatherers existed in Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene times, ‘situationally appropriate’, in part because environmental conditions did not demand such high-cost responses, or, it might be that they had narrower, single-species-focused hunting strategies, like the Clovis mammoth hunters in the

American southwest. More conservative, but arguably more stable, adaptations such as those on the north coast of Peru and in parts of the southeastern United States and of the tropical lowlands of South America, for instance, could thus maintain themselves. Until scientists carry out more research on these and other topics, we will not better understand the uneven early cultural developments that took place across the Americas and the lingering influences that they had on later cultures.

One aspect of early cultures that is poorly understood is social organization. Several archaeologists believe that the shift from hunters and gatherers to agriculturalists and herders in many parts of the world was sparked not only by new technological innovations and the exploitation of new plant foods but also by major changes in the social organization of families and household groups. For early mobile or semisedentary hunters and gatherers, the band model of social organization, with its sharing of resources among members, was probably the most viable way to survive as groups moved and settled into unknown territories. The mobility of bands across unpopulated terrain allowed them to adapt to environmental challenges and to social conflicts. What mobility could not provide in the way of resources, exchange with neighbors could. But eventually some groups settled down, became more socially and culturally complex, and developed into agriculturalists and/or herders. Not until the onset of a sedentary lifeway in parts of the Americas during the Early to Middle Holocene period, can we observe a dramatic reorganization of social and economic relations between neighboring groups. These changes must have been accompanied by changes in the nuclear family and the aggregation of new and larger communities made up of different types of families and social groups that served as the primary units of production and reproduction. These are the transformations archaeologists must begin to identify in order to better understand the ways that laid the foundations for subsequent developments.

World History

World History