In Irish mythology, ravens were associated above all with the fearsome triple goddesses of war and destruction, the Morrigna (singular Morrigan) and the Badbh.49 These Insular ravens represented the bloodshed of the battlefield and the pitiless destruction of man by man. That ravens were linked with warfare in Iron Age Europe is indicated by the presence of such objects as the helmet from Romania, with its movable raven crest (figure 4.17) (see chapters 4, 6).

In Romano-Celtic iconography, ravens were presented not as birds of destruction but as peaceful attributes of beneficent divinities. This may have been due partly to their supposed oracular powers, for which they were apparently used by Irish Druids in divination.50 The Graeco-Roman Apollo was associated both with prophecy and with healing, and the occurrence of raven images at some of these Celtic therapeutic sanctuaries may derive from a similar association. The god who presided over the Burgundian healing spring shrine at Mavilly was depicted in company with a large raven51 and a sick pilgrim who apparently suffered from an eye affliction. It is even possible that the raven's bright eyes represented clear vision. Many of the goddesses are portrayed with ravens as attributes: Nantosuelta is one of the few for whom we have a name. She appears on images at Sarrebourg near Metz and at Speier in Germany, accompanied by a raven.52 Nantosuelta's name means 'Winding Stream', but this gives little clue as to her identity or function. She is normally depicted with her consort Sucellus, The Good Striker, a god whose main attribute was a long-shafted hammer or mallet. The couple seem to have been venerated as bringers of prosperity and domestic well-being:

Nantosuelta's other motifs include a house symbol and a hive; Sucellus often carries a small pot or goblet, perhaps filled with wine. The goddess may have been perceived as a kind of mother-goddess, and it is interesting that in Luxembourg a distinctive type of goddess was worshipped, a deity whose image consisted of a lady seated within a house-shaped shrine and accompanied by a raven. Here again then, the house and bird symbols are associated.53 It is well established that the Celtic mother-goddesses had an association with death and the Otherworld as well as with fertility and florescence. This is why small images of the Mothers are sometimes found in graves and at the bottom of wells.54 So it may be that where ravens are associated with goddesses, they represent the underworld aspect of their cult: it is interesting that one representation of Epona55 depicts her with a dog and a raven; the connection between the horse-goddess and the Otherworld has already been examined.

Other deities appear with dogs and ravens. A sculpture found at Moux in Burgundy56 depicts a peaceful, bearded god dressed in Gaulish breeches and a cloak fastened at the shoulder (figure 7.10). He carries a billhook and three fruits in the crook of one arm and rests his other hand on a knotted club or stick; by his side sits a dog with pricked-up ears. On each of the god's shoulders perches a raven, its long sharp beak pointing towards his head. The inanimate attributes of the god proclaim him as a lord of nature, a pruner of foliage and a gatherer of fruit. His dog may simply be a companion, a guardian in the wild countryside, but the ravens present a symbolism which may reflect the underworld and thus the dog, in this context, may also be a chthonic motif.

Sequana and the water-birds

In 1963, investigations at a waterlogged site north-west of Dijon brought to light an important healing sanctuary, Fontes Sequanae, a spring shrine at the source of the river Seine. The site was particularly rich in votive objects, not only of metal and stone but also of wood, the oak heartwood of the Chatillon plateau. Dedications made by grateful or hopeful pilgrims show that the deity venerated here was called Sequana, goddess of the Seine; her bronze cult-image, recovered from the mud, depicts a serene deity wearing long robes and a diadem, her hands outstretched to welcome her suppliants (figure 8.10). The interesting point here is that she stands in a boat in the form of a duck, the prow fashioned as its beaked head and its tail forming the stern.57 The duck is present here as a simple water symbol, indicative of Sequana's aquatic identity and of the healing powers of the spring-water. Of the many representations of pilgrims in stone or wood, some are shown bearing gifts to Sequana (figure 8.4), gifts that sometimes took the form of birds.

Figure 8.10 Bronze figurine of Sequana in her duck-prowed boat, first century AD, Fontes Sequanae, near Dijon. Paul Jenkins.

Other representations of ducks are recorded from free Celtic and Romano-Celtic Europe58 but most of these occur as isolated figurines, there being no clue to their religious identity. An exception is the combined iconography of the water-bird and the sun, which was a tradition whose origins lay in the later European Bronze Age. In this period, solar symbols ride in boats with water-bird head terminals, on sheet bronze vessels and on jewellery, and sun-wheels and ducks appear together on armour. The association of the solar and water-bird symbols continued into the Celtic Iron Age, with duck-boats carrying suns on bronze pendants, and torcs decorated with wheels flanked by ducklike birds (figure 6.15).59 In this context, the water-bird appears to be an attribute of a celestial deity. We know that, in the Celtic period, the sun-and sky-gods were complicated beings who were linked not only with the heavens but also with water and the underworld. Perhaps the water-bird was perceived as a suitable solar emblem because it was able both to fly and to swim, thus bringing together the elements of sky and water, both of which belonged to the celestial powers. To the pagan Celts, the sun and water were both related to healing, and this perception of the water-bird as a link between the two elements may have resulted in the making of the image of Sequana, the curative goddess of Fontes Sequanae, riding in a duck-adorned boat.

Geese and cranes

In Celtic iconography, geese are most commonly associated with war: thus, because of their watchful and aggressive nature, these birds were perceived as appropriate emblems or companions for warrior-gods. The great freestanding stone goose, gazing alertly from the lintel of the Iron Age cliff-top temple of Roquepertuse in Provence guarded a shrine in which war-deities were venerated.60 The bronze figurine of a Celtic war-goddess from Dineault in Brittany61 depicts a young female wearing a helmet, the crest of which is in the form of a goose which thrusts its neck forward in such a threatening manner that one can almost hear it hissing. In Iron Age Czechoslovakia, warriors were sometimes buried accompanied by geese,62 as if the birds were considered lucky emblems of bravery and aggression which would enhance the image of the soldier in the next world.

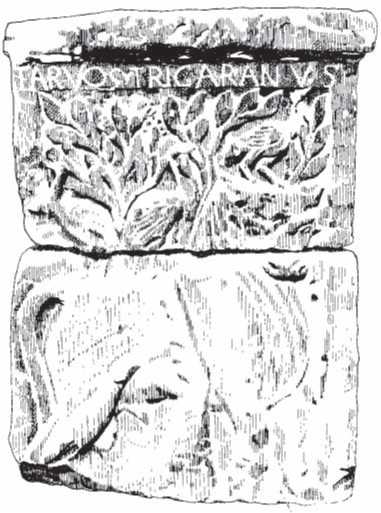

Marsh-birds - egrets or cranes - had a close affinity with the supernatural world, as described in the Insular vernacular sources (see chapter 7). In iconography, the most important crane symbolism occurs on two monuments in the early first century AD, one from Paris, the second from Trier.63 The two stones possess remarkably similar imagery, consisting of the association of a bull with three egrets. The Parisian monument (figure 8.11), dedicated to Jupiter in the reign of Tiberius by a guild of sailors, is made up of several stone blocks: on one a large bull stands in front of a willow-tree, two birds on his back and a third perched on his head; on an adjacent panel, a woodcutter hacks at the branch of a willow.64 The inscription above the bull reads 'Tarvostrigaranus' (the Bull with Three Cranes); that above the man reads 'Esus' (Lord). The Treveran sculpture is virtually identical, in terms of the content of its imagery: here, on a single stone surface, a woodcutter chops at a willow-tree in which are a bull's head and three cranes or egrets. The motifs of tree, birds and bull are all related in life: cranes or egrets and willows both have water associations, and the birds love willows. In addition, egrets and cattle are symbiotically linked in that the birds feed on tics and other pests which infest the hides of the cattle. The whole symbolism of woodcutter, tree, birds and bull reflects a complex mythology of which we can know little but a possibility is that the Tree of Life is depicted, its destruction reflecting the seasonal 'death' of winter and the departure of the tree's spirit in the form of birds. The bull may represent new life and virility, the regenerating strength of spring and the awakening of the earth. The water element could equally reflect the life-force and fertility generated

Figure 8.11 'Tarvostrigaranus', the Bull with Three Cranes, on a stone monument from Paris, early first century AD. Paul Jenkins.

By rivers and lakes. Tarvostrigaranus has no precise parallel outside Trier and Paris, but it is possible that a curious image from Britain may reflect similar symbolism. This is a small bronze figurine of a bull, once covered in silver-wash, from a fourth-century AD shrine at Maiden Castle, Dorset.65 The bull originally had three horns (see pp. 222-3) and has the remains of three female figures on its back. In Irish vernacular legend, women on occasions metamorphosed into cranes (chapter 7), and it may be that, on this figure, women are substitutes for the marsh-birds associated on the Continent with Tarvostrigaranus, thus presenting iconographically a tradition well documented in the early Insular literature.

Doves of peace and healing

Like ravens, doves were perceived as oracular birds, perhaps on account of their distinctive call. In classical iconography and mythology, doves were the attribute of Venus, goddess of love, presumably because of the intimate behaviour of courting doves; the birds came to represent peace and harmony as well as sexual love. In the ancient world, the concept of

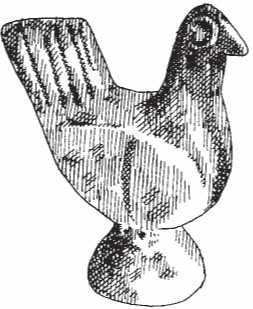

Figure 8.12 Romano-Celtic clay figurine of a dove, Nijmegen, Netherlands.

Paul Jenkins.

Harmony was close to healing: bodily health and peace of mind were perceived to be related. It was perhaps partly for this reason that images of doves were offered to the Celtic healer-deities of thermal springs, particularly in Burgundy. Pilgrims offered multiple stone figures of doves, in groups of two, four or six, to the curative spirits presiding over shrines at Nuits Saint Georges, Beire-le-Chatel and Alesia.66 At Foret d'Halatte (Oise), at Essarois and Fontes Sequanae, pilgrims dedicated images of themselves carrying doves as gifts to the healing forces who resided in the springs.67 At the great therapeutic cult establishment of Mars Lenus at Trier, images of young children held doves as presents for the healer-god, who was especially fond of children.68 Apart from the association between doves and harmony, another reason for the presence of dove images at curative shrines could be that prophecy and healing were linked: the classical Apollo was both a healer and a prophetic god and, indeed, the Celtic Apollo was venerated at both Essarois and Beire-le-Chatel. Oracles, visions and dreams were all perhaps related to the healing process, which was brought about not simply by the treatment of physical symptoms but by methods which depended on holistic concepts whereby mind and body were inextricably bound together and needed to be treated together. Certainly there is evidence that priests at these shrines were also sometimes doctors, who performed surgery in addition to providing the link between the worlds of the profane and the spiritual.

World History

World History