Until around 35 000 BP, traditional lithic industries continue to be present in areas where cultural manifestations were well developed. After this point in time, a number of new lithic technologies (including blade technique, bifacial technique, microblade technique, as well as wide-employment of bone tools) appeared to blend together to create the Late Palaeolithic cultures. This technological diversity resulted from cultural interactions when waves of human migrations from Western Europe spread out across Eurasian. The impacts this had on Chinese Late Palaeolithic cultures were enormous. Diversified technologies clearly replaced the conventional homogeneity in most parts of China during this period; the results may be regarded as a southward intrusion of cultural manifestations from the North and Northwest. Similar technological diversity is also observed in the northwestern coast of North America as a result of the peopling of America around 20000-11500 BP (see New World, Peopling of; Siberia, Peopling of).

Small-flake-tool Technology

During this period, flake tools from northern Late Palaeolithic sites tend to be small in size but delicately made mostly on fine quality cherts. Small flake industries of northern China were well represented by the Shiyu site in Shanxi province, the Xian-rendong cave site of Liaoning province, and the Xiaonanhai cave site of Henan province. Compared to previous flake-tool technology, these lithic assemblages produced flake tools that show better designed and standardized forms. Toolkits included scrapers, burins, small projectile points, drills, notches and den-ticulates, which were made from various raw materials and by different techniques including hard-hammer and soft-hammer percussion. Pressure technique was also developed for making tools that required intensive surface retouching such as bifaces and projectile points. Standardizing toolkits were clearly adapted to northern hunting strategy that mobilized human societies.

Shiyu, identified and excavated in 1963, yielded thousands of flake tools predominated by various shapes of scrapers: most of them were between 20 and 30 mm in length. Their working edges were finely retouched, probably by soft-hammers. Most flake blanks were also observed to be of regular size.

A large quantity of faunal remains was recovered from the site, animal teeth alone counting for roughly 5000 pieces. Faunal analysis suggests most animal species are adapted to a prairie environment - there were at least 200 individuals of wild horses and wild donkeys. It seems that the Shiyu occupants, who lived around 29 000 BP, were wild horse hunters.

Flake-tool industries became more frequent in southern China; but typologically and technologically these flake tools were distinctive from these in northern China, suggesting a local technological innovation. The development of this trend is well documented from the Three Gorge assemblages, through the Ziyang Locality B assemblage, to the Tongliang lithic assemblages. The best examples of the southern flake-tool industry are from the Hanyuan Fuling site of Sichuan province, as well as two cave sites, Maomao-dong and Baiyandong. Flake-tool blanks were made from large pebble/cobble raw materials by anvilchipping or throwing techniques, and then altered along the working edge by retouching in order to make them into suitable tools. However, flake-tool modification was not as extensive as those in northern China, and the toolkits there were not as diverse.

Blade Technology

Blades were occasionally reported or cataloged from the lithic assemblages of early sites, but they were likely a by-product of flake production. During this period, blades as primary products of a special reduction technique appeared in northern China, but archaeological sites with blade production were very limited in numbers so far. The origin of blade technology in China is difficult to trace to local flake-tool technology, thus it is probably derived from western influences. There are nearly two dozen sites where blades have been reported, all of them situated in northwest and north-central China. However, true presentations of blade technology are from only two sites, Shuidonggou and Youfang.

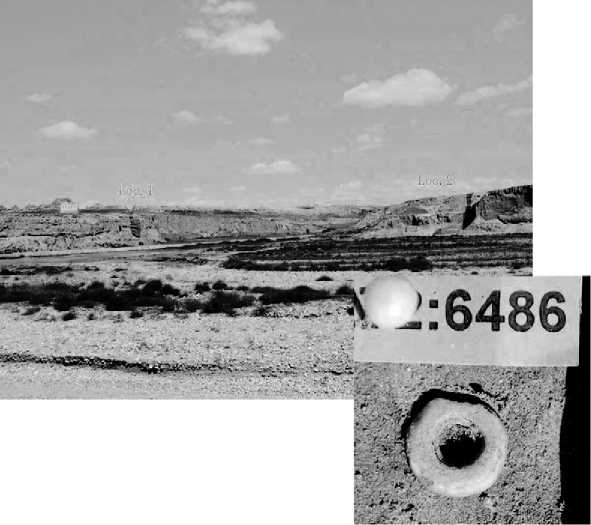

Shuidonggou, located at southwestern part of the Ordos area about 18 km east to the Yellow River, was the first Palaeolithic site excavated in China by French palaeontologists E. Licent and P. Teihard de Chardin. They reported five locations at the site and excavated the Locality 1 in 1923. Because of classical blade production, the findings from Shuidonggou made an immediate connection between remote Chinese cultures to the western ones; thus, the site has been a focus of study and most of the collection is now housed in western institutes and museums. Follow-up excavations at the site took place in 1960, 1963, and 1980, and produced a large quantity of lithic artifacts and faunal remains. Unfortunately, like many of other sites investigated prior to 1990, this site was not systematically studied with a multidisciplinary approach until 2002. Recent surveys reported that the site complex consisted of 20 localities. Excavations during 2003-2004 were concentrated at Localities 2, 7, and 8 (Figure 22). Besides lithic artifacts and faunal remains, the site also yielded

Figure 22 The landscape of the Shuidonggou Site and ornaments (insert) recovered from the 2003-2004 excavations.

Fired clay floors and ash deposit indicative of purposeful fire use. Most importantly, dozens of finely polished ostrich shell ornaments (rings) were recovered from Localities 2 and 8. A skull fragment, found at Locality 4, was identified as Homo sapiens sapiens.

The Shuidonggou lithic assemblage is dominated by blade cores and blades, made on local cherts and quartzite. Core platforms were well prepared before blade removal indicating standard reduction procedures. Notably, 21.9% of cores recovered from the 1980 excavation session were classified as Levallois cores, which were also found from other excavation sessions. Although Levallois-like products were reported from the Panxian Dadong cave, the true Levallois technique seems to be only from Shuidonggou. Unfortunately, there is no detailed study on these Levallois cores and flakes yet, but their appearance at the Shuidonggou site is a clear indicator of western influences. Most of the retouched tools, represented by side-scrapers, were made on long narrow blade blanks. Samples of Uranium-series dating and conventional 14C dating indicate the age of Shuidonggou fall in between 38 000 and 15 000 BP, but recent AMS 14C dating suggests a narrower range of between 29 000 and 24 000 BP. According to faunal analysis, pollen, and sediment studies, Shuidonggou was a part of cool and dry semi-steppe and prairie environment during this time, thus the site might have served as a base camp for a group of specialized hunters.

Shuidonggou blade technology seemed to remain the sole manifestation in China until the middle of the 1980s, when the Youfang site was excavated. The site is located in the east side of the Nihewan Basin, and slightly later in age than Shuidonggou. Youfang blade technology coexisted with microblade technology; however, most of the flake tools were made on classic blade blanks. Single platform cores display parallel long and narrow blade flaking scars, some with evidences of direct percussion. The discovery of the Youfang lithic industry suggests that such blade technology continued to spread eastwards in northern China at the end of Pleistocene.

However, the lack of detailed study on Chinese blade technology keeps scholars from understanding statistical data that might be able to assist in a comparative study with western assemblages. Until then, how blade technology was developed and why its distribution was so limited remains unknown.

Microblade Technology

The Youfang lithic assemblage is to date the only example in China, where both blade and microblade technology were employed within a given hunter-gatherer society. Archaeological evidence suggests that early microblade industries were found in the southern Shanxi province, about 500 km south of Shuidonggou, suggesting an independent emergence from the blade technology. Both Dingcun 77:01 and Xiachuan sites were regarded as the earliest examples of microblade technology, dated to around 26 000 BP and 24 000-16 000 BP, respectively. The later microblade industries are represented by the Shizhitan site in Shanxi province and Hutongliang site in Hebei province.

At present, there are over 50 sites reported to be associated with microblade technology. They were distributed over three microregions: the north-central plain, the northeast and northern steppe, and the southeastern plateau, but the majority of the microblade sites were located in north-central China. Current knowledge of Chinese microblade technology is derived only from a few well-known sites such as Xiachuan, Xueguan, and Hutouliang. Hutouliang is an archaeological complex consisting of a number of the Upper Palaeolithic sites, located in the east side of the Nihewan Basin, about 35 km west to the Early Pleistocene site Donggutuo (see above). Nine localities were excavated between 1972 and 1974, and yielded a large quantity of lithic artifacts. Based on a series of 14C dates the sites were dated to around 11000 BP. Analyses of these microblades identified four microblade techniques at the site, which have corresponding Japanese counterparts known as Yangyuan (or Togeshita), Sanggan (or Oshorakko), Hetao (or Yubetsu), and Xiachuan (Saikai). A recent study indicates that two types of wedge-shaped core technology existed as by-products of the modes of production at the Hutouliang site.

Studies on microblades from both Xiachuan and Xueguan in southern Shanxi province were based on limited excavated and surveyed materials, and suggested technological differences existed in the manufacture of microblade between Xiachuan and Xueguan. The Xiachuan industry is represented by conical microblade cores while the Xueguan microblade industry is dominated by boat-shaped and wedge-shaped cores. It is proposed that microblade technologies at both Xueguan and Hutouliang were developed directly from the Xiachuan technology, implying that Xiachuan may be responsible for the origin of Chinese microblade technology. Data from other excavated sites like Shizitan, Dingcun 77:01, Youfang, Jiqitan, and especially Qingfengqing and Fenghuangling in Shandong province would have merits that may challenge traditional views on microblade technological development. For instance, microblades from the East Coast like Shandong

Peninsula display distinct technological characters so that it may be possible to recognize regional microblade variation. Unfortunately, materials from these sites have not been systematically studied yet.

Microblade technology in China is still poorly understood in terms of its origins and spread throughout northeastern Asian. Most Chinese scholars tend to favor a ‘north China origin’ model. Data from the region clearly indicate technological similarities between northern China industry to those from Eastern Siberia, Japan, and Korea. A recent study suggests an eastward spread of microblade technology that originated at Xiachuan, through northern and southern routes, but the hypothesis is not yet tested. It is worth noting that some scholars have started to hypothesize that wedge-shaped core microblade technology might have first emerged in Siberia and spread southward into northern China.

Bifacial Technology

Bifacial technology appeared in northern China as a result of cultural interactions with northern hunter-gatherer societies during the peopling of the Americas. Northern China lithic assemblages produced tools that were made through bifacial-thinning techniques; but again, this technological catalog unfortunately has not yet been recognized in Chinese Palaeolithic studies. Bifaces and projectile points, a major component of stone toolkits in the North American assemblage around 11 500-10 000 BP, also appeared in the Xiachuan, Xueguan, and Hutouliang sites, but their significance has not been yet given much attention. A recent study on Upper Palaeolithic sites in Shandong Peninsula shows that biface products have high frequency in lithic assemblages at the Fenghuangling, Qingfengling, and Wanghailou sites, suggesting bifacial techniques existed as a technological innovation at the end of Pleistocene.

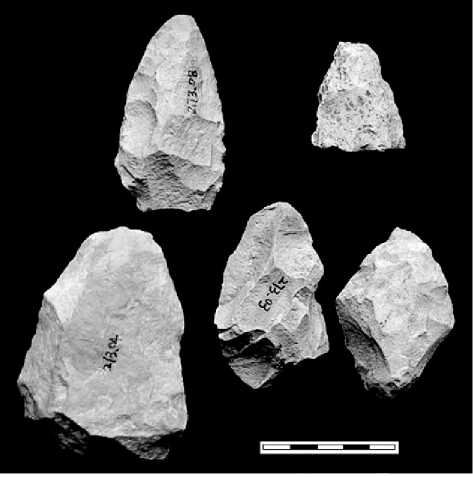

These three sites (Fenghuangling, Qingfengling, and Wanghailou) are located in southern Shandong province, near the Yi-Shu Rivers valley. Both Fenghuangling and Qingfengling were floodplain sites and were excavated in 1984. The Wanghailou site, located in the hilltop about 68 km south of Fenghuangling, was surveyed in 1984, and excavated in 2001 by a Sino-Canada collaborative team. The three assemblages belong to two Shandong microblade industries. Lithic analyses of the assemblages suggest that bifacial thinning flakes from Fenghuangling, Qingfengling, and Wanghailou may serve as a kind of index-fossil of by-products of bifacial techniques, and account for 30.3%, 20.3%, and 14.7% of all lithic artifacts recovered, respectively. Bifaces and biface performs as types in the toolkits comprise

Figure 23 Bifaces from the Wanghailou site in Shandong Peninsula (scale in mm).

Between 5-20% of shaped tools. It is possible that Shandong microblade cores were primarily produced through bifacial techniques - the wedge-shaped cores were made on small bifacial splits that also occurred in the assemblages. Large-sized projectile points, finely made on quartzite were distinct at the Wanghailou site (Figure 23), while bifaces and projectile points were relatively small at the other two sites. During an investigation in 2004, a special point (one where a channelled flake was purposefully removed from the bottom so as to be called as ‘fluted point’) was identified from the Qingfengling site. Fluted points had never been identified previously in China; however, fluted Clovis points are well known as an early industry in North America. The fluted point industry was clearly associated with wedge-shaped microblade core industries in British Columbia, Canada, at the end of the Ice Age. If a true fluted bifacial technology is proven to have existed in northern China, the technological connection between the Old World and the New World can be explored in addition to the microblade technology.

Bone Tool-making Technology

Another technological innovation in the Late Palaeolithic cultures is bone tool-making. In fact, bone tools must have appeared during the Middle Pleistocene, or much earlier, as they were seen in Jingliushan, Zhoukoudian Locality 1, and Xujiayao sites. However, only at the end of the Pleistocene did using animal bones (including antlers) as raw materials for manuacturing various tool types appeared widely and bone tools became one of the major components of hunting-gathering toolkits. The bone tool industries were well represented by following sites: Shiyu in Shanxi province, Xianrendong Cave in Liaoning province, Lingjing in Henan province, and Dongfang Plaza in Beijing.

The Dongfang Plaza site was identified in 1996 when the Plaza complex was under construction in downtown Beijing, and excavated in the following year. The site is approximately 2000 m2, and yielded thousands of artifacts including bone tools. According to the excavators, 411 bone tools were cataloged and classified into various manufacturing stages. Shaped types, indicated by retouched working edges, included scrapers, point, burins, and spades. Most of the tools were made from the long bones of large mammals. The stone and bone tools were associated with floors with evidence of fire-use. Some bone tools and by-products displayed burnt marks, indicating that the site might have served as a homebase camp for late Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers. Carbon-14 dates suggest that the site was occupied for two phases between 25 000 and 24 000BP.

Recent excavation at the Lingjing site near Zhengzhou city yielded significant bone-tool assemblages that previously have been rarely seen. The Lingjing site was first identified in 1965 during local water-storage construction, and the survey collection included an assemblage of wedge-shaped microblade cores. As a result, the site was referred to as the ‘Mesolithic’ period in northern China in many publications, but full-scale investigations were not able to be carried out due to underwater inundation until 2005. The 2005 field session recovered 2452 lithic artifacts and over 3000 faunal remains. However, no microblade products were recovered from excavated layers; most lithic artifacts were typical of the flake tools from northern China, and made from quartzite and quartz. At present, according to the excavator’s observation, this site represents a Late Palaeolithic occupation.

Some bones display clear secondary retouch for modification. Samples were taken for use-wear examination, and the preliminary study suggested a number of possible use-wear features that may be differentiated from natural abrasion. Similar to use traces of stone tools, the use-wear on Lingjing bones were likely that of cutting, scraping, and penetrating. The use-wear also shows traces of soft, moderate, and hard-worked materials. Mostly importantly, 3 of 11 samples were determined to have hafting wear, suggesting that these objects had been used as composite tools. However, study of Palaeolithic bone tools in

China is still very poor, and caution needs to be taken in understanding how to distinguish purposeful use-wears from fracture/abrasion marks caused by natural agencies at sites. The fact that bone tool-making technology existed in Upper Palaeolithic assemblages has merits to provide new directions of research in the future (see Bone Tool Analysis).

World History

World History