During the reign of the legendary Chinese emperor Yao, ten suns shone in the sky at the same time, causing rivers to dry up and the earth to become barren. By dint of blind perseverance and determination, the hapless people of this drought-stricken land managed to eke out a meager livelihood—but just as they were beginning to prosper, a great flood swept over the world and reduced them again to misery.

So begins an account dating from several hundred years BC of the beginnings of Chinese civilization. But the story goes on to tell how, with divine help, the destructive forces of nature were eventually tamed, and order and control were brought to the land. A god named Gun took pity on the suffering people and, using a piece of soil with magical properties, built a dam to hold back the floodwaters. Gun was killed by the angry god of fire, and again the waters covered the land. But Gun's spirit refused to die, and after three years, a son, Yu, emerged from his corpse. Yu was able to obtain the services of a winged dragon and also a new supply of the magical soil, which he used to stop up the 233,599 springs from which the water was emerging.

Yu next turned his attention to the floods that still covered the landscape. For thirteen years, he traveled by boat on water, by sleigh over marsh, and by cart on land; he did not stop to enter his own house even though he passed by the gate. In this manner, he surveyed the land and marked off the boundaries of nine provinces; he also cut deep channels that became the great rivers of China, made passes through the mountains, and built dikes in the low-lying plains. Yu also fathered a son, Qi, who became the founder of the first hereditary dynasty in China.

Floods and drought have repeatedly punctuated the course of Chinese history, and Yu's efforts to bring order and stability to this troubled land speak for the experience of countless generations of ordinary Chinese people. Their successes have always been precarious: Famine has so often canceled out the labor of hundreds of thousands of families that for most Chinese, for most of the time, bare subsistence has been the only realistic goal. But their achievement, however hard won, is undoubted. The Chinese now have a life expectancy—sixty-eight years at birth for males and seventy-one years for females in 1988—that is higher than that of the U. S.S. R., India, and any nation in Africa, and comparable to that of the richer nations of the Western world, which are themselves less subject to natural calamities.

In coping with the natural disasters that beset their land and also with the economic problems of feeding an enormous population, the Chinese and other peoples of eastern and southern Asia have resorted to methods of agriculture very different from those characteristic of the West. From at least the beginning of the nineteenth century, America and Europe have fed their own citizens by the evermore intense application of industrial technology. In China and India, other strategies—determined by the land itself and by cultural attitudes toward it—have prevailed. The effects have been most

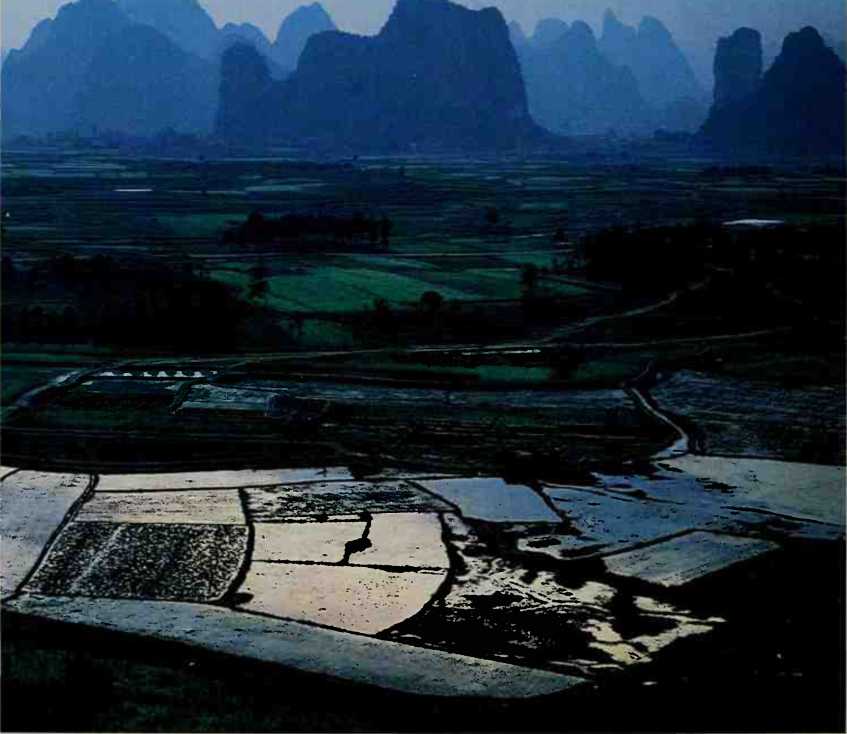

The hand of the farmer has transformed this landscape near Yangshao in southern China into a patchwork of fields interlaced with irrigation canals. Because of the pressure of supporting an enormous population, every cultivable piece of land up to the edge of the sheerrising mountains is used to produce crops: rice in the flooded paddies, and wheat, beans, vegetables, and tobacco in the dry fields.

Apparent in the biological sphere: the introduction of new varieties of crops, many of them developed for growing on inferior land, and of labor-intensive systems of agriculture that have made efficient and economical use of natural resources. China and the Orient have prospered not so much by mastering nature as by the patient expenditure of infinite amounts of human energy and minute attention to detail.

Present-day China is the third-largest nation in the world and home to more than one billion people, one-fourth of the earth's population. But such impressive statistics conceal an immense variety of terrains, of peoples, and of cultural traditions. If China

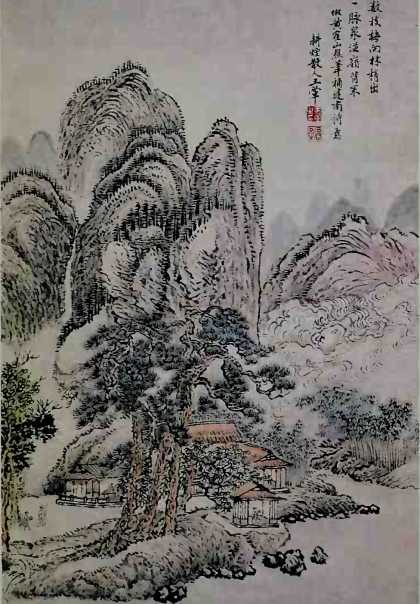

Simple human habitations nestle by a lakeshore in this scene from a scroll painted in ink by the seventeenth-century Chinese artist Wang Hui. Rejecting realism, traditional Chinese painting favored harmonious, idealized compositions in which the pulse of nature was expressed in the forms of lofty peaks, surging waterfalls, and branching trees. Such works embodied reverential attitudes toward the natural world that coexisted with its necessary and increasing exploitation.

Exists at all as a unified entity, in the minds of both outsiders and the Chinese themselves, it is only because of a long historical process that involved the development and implementation of complex and resilient forms of political control; an eclectic but unifying culture; and methods of working the land that rely above all on cooperation and shared endeavor.

Astronauts orbiting the earth have reported that the only construction visible from space is the Great Wall of China, the barrier erected along the northern frontier to protect the settled Chinese from their nomadic, aggressive neighbors. As they tumbled toward the earth and the surface of the globe came into sharper focus, the astronauts might have noticed that China comprises two distinct geographical regions. Inner China, forming a rough square bordered to the south and east by the sea, is a land of alluvial plains and river valleys, a patchwork of tiny fragments of every shade of green and brown. The historical core of the Chinese empire until the seventeenth century, this terrain is home to about 95 percent of the population. On its northern and western sides, it is wrapped around by outer China, a region of greatly contrasting topography. Outer China includes the world's highest mountain— Mount Everest, towering 29,028 feet above sea level—and the second lowest point on the earth's surface, the Turfan depression, 426 feet below sea level. It encompasses the burning deserts of the Gobi and Takla Makan; the rolling, grass-covered steppes of Mongolia; and vast tracts of swamp and virgin forest. Not surprisingly, large areas are uninhabited, and the overall population density does not exceed 2.6 people per square mile. Recent centuries have seen the migration of substantial numbers of people from inner China into parts of outer China, notably Manchuria, but these peripheral regions are still primarily the homelands of the Mongols, Tibetans, and other peoples who make up fifty-four of the fifty-five ethnic nationalities recognized by the People's Republic of China.

Inner China in turn can be divided into two distinct areas. From the mountainous region to the west, the Qinling and Daba ranges of the Kunlun Mountains extend like a finger and thumb to grab the trailing line of the Han, a tributary of the Yangtze River. This river and the mountains it threads into define the boundary between very different climatic and geographical zones.

South China—as also the whole of Southeast Asia— ranges from the temperate to the subtropical in climate. In the Sichuan basin and toward the South China Sea, temperatures and rainfall are high, and the growing season lasts nearly year-round. In ancient times, the land was covered by dense forests of pine and bamboo, home to creatures such as elephants and giant lizards; the human inhabitants occupied the coastal lowlands and valleys and supplemented their simple agriculture with hunting and fishing. Farther north, in the Yangtze Valley, rainfall is lower, and there is a tendency toward dry winters. Summers are hot and long, and the growing season lasts nine to ten months. The first-century historian

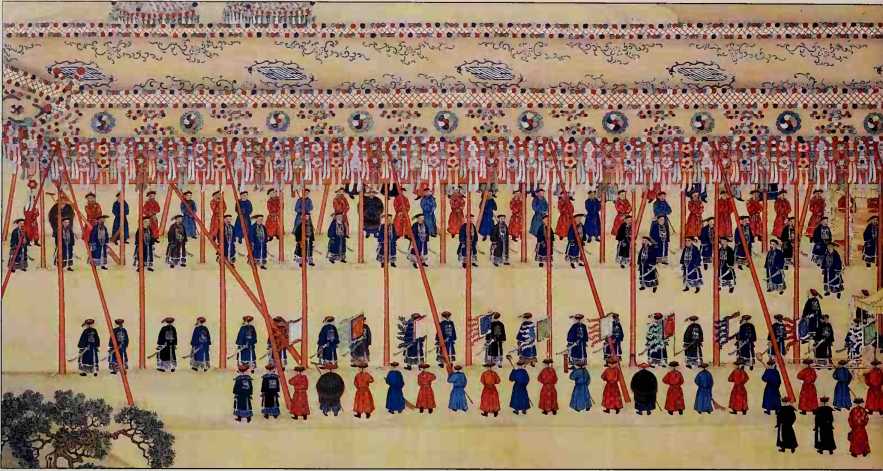

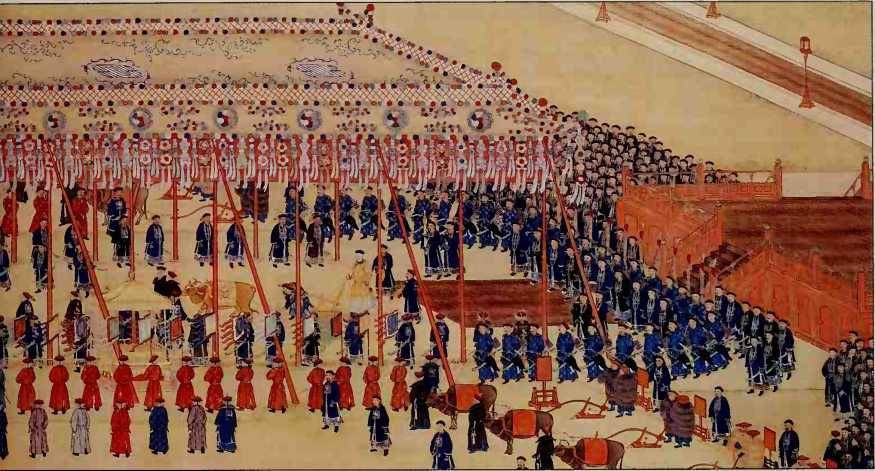

An eighteenth-century silk scroll shows ranks of courtiers under a lavish canopy attending the emperor— descending from the dais on the far right—who is about to plow the first furrow of the year. Parallel with the emperor and awaiting his lead, high ministers stand behind their own plows. In addition to performing this ceremony, intended to ensure a successful growing season, Chinese emperors since the earliest dynasty were expected to offer a sacrifice each spring and autumn at the altar of the spirit of the soil. These customs suited imperial interests: Good harvests lessened the likelihood of rebellion, and most of the emperors' revenue derived from taxes on land and produce.

Ban Gu wrote an observant if subjective description of the lifestyle enjoyed by the denizens of this region during the fourth century BC:

The people live on fish and rice. Hunting, fishing, and wood gathering are their principal activities. Because there is always enough to eat, they are a lazy and improvident folk, laying up no stores for the future, so confident are they that the supply of food and drink will always be replenished. They have no fear of cold and hunger; on the other hand, there are no rich households among them. They believe in the power of shamans and spirits and are much addicted to lewd religious rites.

To the north of the Yangtze lie wide plains through which the Yellow River, the second of China's two great arteries, passes. The plains are covered by a fine, yellow loess that was picked up by winds from the deserts of central Asia during the end of the glacial period and deposited over the northwest of China, sometimes to a depth of several hundred yards. Loessial soil is easily worked and fertile, and about 500,000 years ago, it would have been pierced by outcrops of forest-covered rock, a source of both timber and water. Here, where the Yellow River emerges from the mountains but is still protected by hills, the first Chinese people lived.

As early as 5000 BC, communities of farmers were living in villages in what are now Shaanxi and Henan provinces in northern China and in the settlement of Long-shan, farther to the east in modern-day Shandong province. Their houses had walls of wattle and daub and floors of beaten earth. They had domesticated dogs and pigs and had developed sophisticated techniques of making and decorating pottery. Using

Implements of stone and wood, they cultivated millet, wheat, beans, rice, hemp, cabbage, and melons. Gradually, agricultural prosperity led to the development of cities, the first of which were probably established by clans headed by warrior-leaders whose dominance was ensured by their possession of bronze weapons and horse-drawn chariots. The Shang kings of the seventeenth to the twelfth centuries BC indulged in great hunting expeditions as training for their endless forays against other cities and against less-developed peoples occupying the surrounding countryside; the remains of elephants, rhinoceroses, bears, tigers, leopards, deer, monkeys, foxes, and badgers have been found on their hunting grounds. The staple crops of wheat and millet supported a growing population, and the kings were able to call on the services of scribes and other officials who were not involved in the production of food.

As the use of bronze technology expanded, peripheral regions were settled and brought under cultivation, and the increasing grain production supported larger armies. One by one, smaller and weaker states were subsumed until, in 221 BC, the state of Qin commanded a unified Chinese empire for the first time. The Qin state sought to establish its authority with systematic vigor: Texts deemed subversive were proscribed; weights and measures were standardized; travel was allowed only with a permit; and armies of corvee labor were drafted to undertake massive irrigation and road-building works. But the death of the first emperor was soon followed by rebellion, and in 206 BC, a new dynasty, the Han, was established. The next 400 years of the Han dynasty saw the expansion of Chinese culture to a large part of inner China.

Great numbers of people had already migrated south, fleeing wars or natural disasters that threatened the stability of life in the Yellow River homelands. Around the fourth century BC, more than one-third of the registered population of North

China, approximately two million people, had moved south of the Yangtze; and in the wake of mass migration to well-endowed regions such as the Sichuan basin, people were further displaced to the south and southwest. The Han rulers encouraged such population movements: Seeking to maintain control of the trade routes to the West and to central Asia, they established self-sufficient colonies of farmer-soldiers in the fertile river valleys and settled as many as 700,000 colonists in the Gansu corridor in the northwest at the end of the second century BC. Those peoples who did not submit to Chinese rule were pushed out of the cultivable lands and forced to adopt a pastoral, nomadic way of life on the steppes beyond.

Trade filled the Han coffers to overflowing: The Roman Empire's insatiable demand for silk and Chinese spices ensured a continuous stream of merchants along the caravan route through central Asia known as the Silk Road, the balance sheet being very much in favor of the East. Agriculture, too, brought a new measure of stability. Zhao Guo, an official at the Han court during the first century BC, recommended plowing wide and deep furrows; when the seedlings sprouted, the soil from the ridges was piled around them, until the field was level. Such methods made harvests more secure and were put into practice throughout the empire.

At the same time, a diverse range of intellectual and religious influences was shaping distinctive cultural attitudes toward the natural world. Among these influences were the ancient concepts of yin and yang—complementary but opposing forces that represent darkness and light, female and male, weakness and strength. Yin and yang were believed to rise and fall cyclically, a theory that was used to explain the pattern of birth, death, and rebirth in the natural world as well as the progression of the seasons. All human and animal activity was believed to have its optimum point in the cycle, and to carry out an activity outside the appropriate time spelled disaster. The influence of yin and yang could be channeled by judicious human intervention, however. In his account of his travels in China during the ninth century, the Japanese monk Ennin reported the following traditional method of controlling the climate: "When, seeking good weather, you block the north road, yin is obstructed and yang then pervades and the skies should clear. When, asking for rain, you block the south, yang is obstructed and yin then pervades and rain should fall."

The teachings of the philosopher Confucius, who lived in the sixth century BC, provided justification for the exercise of authority both in the state and in the family by concentrating on form and ritual. Ideal standards of conduct for everyone from rulers of state to children were defined, and exemplary individuals were held up as models. From a Confucian point of view, natural disasters and political downfall were both seen as the result of a failure to observe the correct rites.

A very different way of understanding the world counterbalanced the somewhat conformist doctrines of Confucius and his followers. Laozi, who was believed to have lived during the same era as Confucius, and his successor Zhuangzi were interested in attaining freedom from man-made restrictions and rules, hoping thereby to achieve enlightenment—that is, an understanding of the Dao, or Way, the principle underlying the universe and all creation. Those in search of the Dao were often inspired to become hermits, finding a solitary life in a mountain retreat more conducive to contemplation on such matters than the hurly-burly of society. Such a life was portrayed by generations of Chinese painters in their pictures of mist-shrouded mountains on which the tiny figure of a white-haired scholar gazes from the shelter of his rustic pavilion. The fifth-century writer Rung Zhigui described the ideal toward which

Daoist recluses should aspire: "A man who, incorruptible, holds himself aloof from the vulgar; untrammeled, avoids earthly concerns; and vies in purity with the white snow, ascends straight to the blue clouds."

Later Daoists claimed to have received revelations of sacred texts, and Daoist cults devoted to religious healing achieved a popular following. Seeking to escape the penalities of mortality, some Daoists put their interest in natural phenomena to use in the quest for the elixir of life—although for those whose chemical experiments made use of poisonous materials such as cinnabar, this search sometimes brought about the exact opposite of the desired result. Daoist priests, based in temples set in remote parts of the countryside, collected and categorized herbs and medicinal plants, compiling important pharmaceutical natural histories. Often, they noted surprising—and unproved—associations between natural phenomena: "When in the mountains there is the x/a plant, a kind of shallot," according to a Daoist treatise written about AD 800, "then below gold will be found. When in the mountains there is the ginger plant, then below copper and tin will be found. If the mountain has precious jade, the branches of the trees all around will be drooping."

Daoist priests became practiced in the art of geomancy—known in Chinese as fengshui, or "wind and water"—which ensured that tombs and buildings were not sited in locations that disrupted the powerful forces believed to run through the landscape. Despite offical disapproval, geomancers still operate in rural China.

A third body of thought to make a lasting contribution to Chinese attitudes toward their world was of foreign origin. Buddhism was introduced to China in the first century AD by Indian missionaries following the traders on the Silk Road. It was first adopted by the upper echelons of Chinese society and underwent substantial transformation as the belief became more popular. In China, for example, the Buddhist

Both blessing and curse, China's waterways nourish agriculture and—by flooding adjacent plains at irregular intervals—threaten mass devastation. Since at least the third century BC, armies of laborers have toiled to construct irrigation canals and flood-proof dikes; their largest project was the building in the seventh century of the Grand Canal, shown overleaf, whose main function was to transport grain over a distance of about 620 miles from the south to the north. A detail on the right from a seventeenth-century scroll shows workers bringing a tied bundle of reeds to repair a dike while others hurry by carrying mattocks and baskets of earth. Some overseers offered prizes of meat, wine, or clothes to the fastest workers.

Concept of the transmigration of souls was developed into ideas of paradise and the underworld that were quite alien to Buddha's original teachings. But the promise of peace and plenty after death had a widespread appeal to a population whose earthly lives were both exhausting and perilous. An ancient adage neatly summed up the pragmatic attitudes of the Chinese toward their eclectic cultural traditions: "Confu-cian in office, Daoist in retirement, Buddhist as death draws near."

The first Chinese census was conducted in the year AD 2 and numbered the population of the Han empire at around 60 million. The borders were still insecure, and the people within the empire followed many different ways of life, but the very fact that the census could be taken indicated that a strong central authority had been established over a vast area. A major contribution to this unity was the degree of communal effort required to bring the land under human control and make it bear sufficient produce for a growing population.

The first imperative was to harness the potentially destructive torrents of the major rivers. Vast armies of laborers were mobilized to erect dikes to confine the waters of flooding rivers and to dig ditches to divert this resource for soil irrigation. All the major rivers of China, the Yellow River in particular, pick up large amounts of soil as they cut through the hills and mountains in their upper reaches. This load is carried downstream until, as the flow of the river slows upon reaching the plains, it is deposited on the riverbed, thus raising its level and causing the water to burst its banks. The Yellow River, known as China's Sorrow, carries some 1.6 billion tons of silt annually and has changed its course dramatically during the past 2,000 years—

From following a path almost due north, to debouching south of the Shandong Peninsula, and then moving back again to emerge where it does today in the Bo Hai gulf. In some parts of the alluvial plain, centuries of dike building have resulted in the river's being raised many feet above the surrounding landscape.

A complex system of irrigation canals in the low-lying delta both evenly distributed water over the land and, by means of reservoirs, enabled water to be stored for times when rainfall was scanty. The building of irrigation channels and dikes had a further effect on the soil of the delta region: The silt dredged from the canals during periodic clearing was deposited on the fields, creating a layer of topsoil that sometimes reached depths of more than three feet.

The most ambitious project designed to put water to productive use was the construction of the Grand Canal at the beginning of the seventh century AD. The canal's primary purpose was to enable the rice grown in the Yangtze Delta region to be transported quickly and cheaply to the capital in the north and to the soldiers stationed on the northern frontiers; because of the absence of a good road network, especially in the southern part of the country, it was also used for many other kinds of traffic. The canal began in the fertile fields of the Yangtze Delta and then crossed the low-lying Huai River valley, incorporating conveniently placed tributaries in its path; a northeastern arm reaching as far as present-day Beijing served the garrisons there. It was built by a conscript force of 5.5 million laborers supervised by 50,000 guards, and in the ensuing centuries, workers were drafted by the hundreds of thousands for periodic repairs.

Raising water from canals to irrigate the fields required the use of pumps, powered

By the wind, animals, or more usually, people. Simple devices such

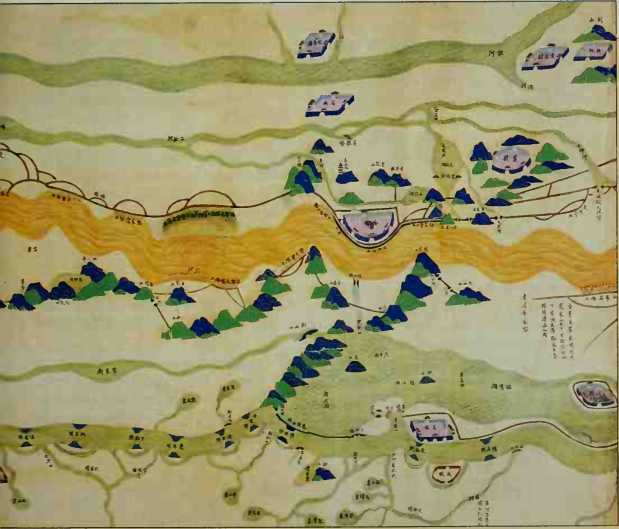

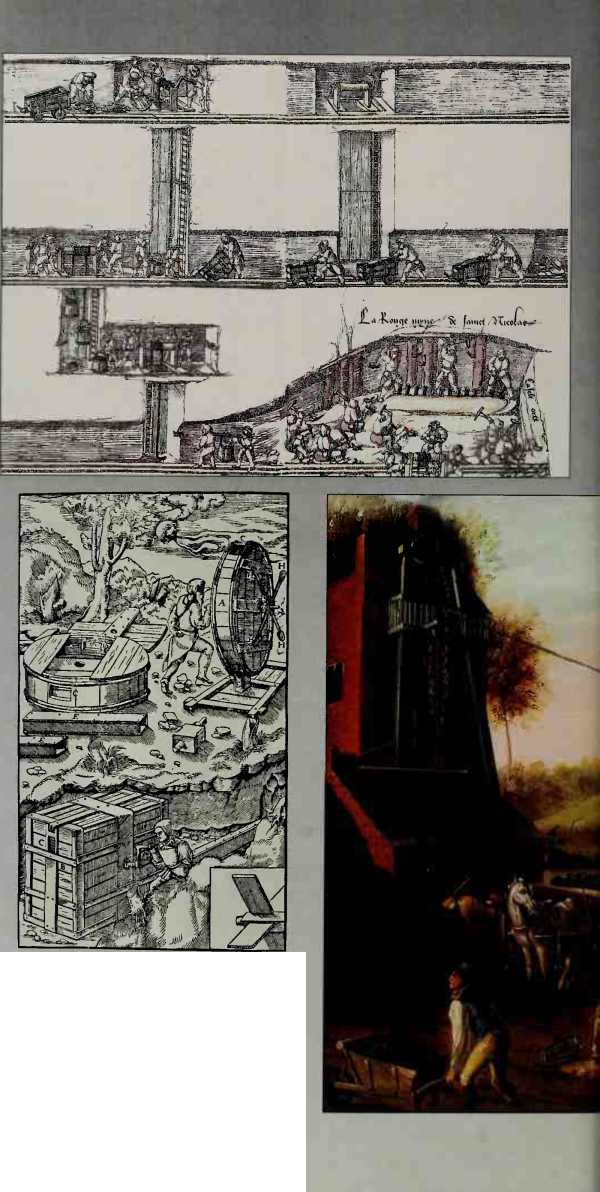

A section from a forly-six-foot-long scroll map of the Grand Canal (left) drawn in the eighteenth century depicts the junction of the canal with Lake Luoma and the Yellow River and the beginning of its southward course to the Yangtze River. That the canal is shown here to run parallel to the Yellow River (colored yellow) is the result of a distortion of directional values that allows the map to include an abundance of information of benefit to contemporary administrators. The boxed details above show symbols representing (1) dikes to prevent flooding; (2) the placement of gabions, the stone-filled bamboo cages used to repair dikes; and (3) locks in the canal. Also recorded here are mountains, springs, towns, and bridges. The passages of writing are lists of villages and families responsible for the maintenance of specific dikes.

As the well sweep, a counterbalanced bucket, and treadmills, which consist of a chain of buckets or paddles that carry or push before them a supply of water, are still in use in many parts of China. A more sophisticated device introduced in the tenth century is the noria, a form of giant waterwheel whose highest scoops spill water into a pipe that is carried on props over the adjacent fields. Where a fast-flowing river is the source of power, the noria can be self-propelling. A twelfth-century poet considered these devices worthy of praise in verse:

Ten tubes upon each wheel both drain and irrigate,

Rising and falling in a circle without cease.

Rich lands have been opened up in the surrounding hills,

Along ten thousand acres wind rice-sprouts like green clouds,

Clouds that before your eyes turn from green to gold.

And fill all stomachs with the year's rich harvest.

The crop celebrated by the poet was grown mainly in the south, where rainfall conditions were ideal, and as this region became more populated, rice gradually supplanted wheat and millet, the more ancient staples of northern China. Indeed, it was to become the most plentiful crop of the entire world: Approximately one in twenty-five of the earth's arable acres is now used for cultivating rice, which provides more than 650 calories per day for every man, woman, and child.

The highly efficient system of air passages leading from the leaves to the root of the rice plant enables it to grow in waterlogged conditions that would drown most other crops. Some varieties of rice can survive under floods up to sixteen feet deep, growing almost ten inches a day to keep their leaves above the rising waters. And far from being a handicap that the plant has had to overcome, water in fact promotes its growth: Controlled flooding both prevents nutrients from escaping into the atmosphere or the subsoil and makes for a highly efficient supply of nitrogen and phosphorus, the two most important plant minerals. Without the aid of artificial fertilizers, well-tended rice fields can produce two or three harvests each year for centuries from the same area of land.

Rice growing was and remains a highly labor-intensive activity. There are no mechanical devices that can perform the tasks of sowing the seeds in prepared beds, transplanting them to paddies after about one month's growth, and then weeding and harvesting them with the same efficiency as human hands. When traditional methods of cultivation are employed, every few acres of land require between 1,000 and

2,000 hours of labor to produce just one harvest. In addition, a high degree of human organization is needed to control the use of water in the rice paddies and on the terraces that have been cut into hillsides: Because the land must be dry when the rice is harvested and remain so for a short time afterward, growing cycles must be staggered in order to ensure continuous productivity. The amount of labor and coordination required, however, have themselves contributed to the stability and enduring success of this form of agriculture.

Where conditions determined their need, further sophistications were built into the system. If the growing season was not long enough to allow successive harvests, intercropping was practiced, in which a second planting of seedlings was set out in alternate rows a few weeks after the first. And where land suitable for cultivation was in short supply, different types of plants that could be harvested without mutual

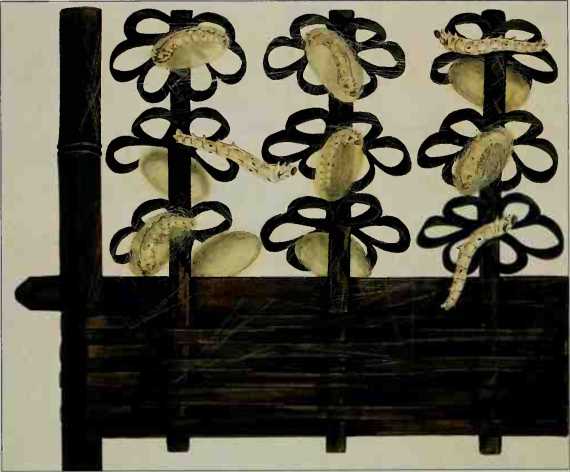

On a bamboo lattice, silkworms that have been fed on mulberry leaves spin the fine silk fiber secreted by their glands into shell-like cocoons. The candor of this painting, produced for export in the nineteenth century in a style designed to appeal to European tastes, contrasts with the jealousy with which China guarded its monopoly on silk production for more than 2,000 years. By the eleventh century, sericulture—the art of raising silkworms—had spread to Japan and, via India and the Arabian Peninsula, to Europe.

Interference were interwoven in rows. A Han dynasty text recommended growing scallions under melon vines, and other works suggested combining onions and coriander, and turnips and hemp.

To ensure that the yields generated by such intensive farming stayed high year after year, the Chinese peasantry developed elaborate methods of maintaining the fertility of the soil. Organic material dug into the soil to improve its nitrogen content included leguminous plants such as green beans, mud taken from rivers and canals during dredging operations, animal dung, and night soil—that is, human excrement. Farmers augmented their own family's production of this vital resource by building latrines at the side of the road for the use of passers-by, to mutual benefit. In cities, night soil was collected each morning and transported out to the countryside either to be applied directly to the fields or to be dried for later use. The sight of euphemistically named "honey wagons" being pulled along city streets by horse or by people is still a common one. The cumulative effect of the nurturing of the soil over generations is evident in the high humus and nitrogen levels of the zones around cities.

In addition to the staple cereal grains of wheat and rice, the Chinese peasantry grew a range of other crops. A guide for the improvement of rural life written in the sixth century AD gave advice on the cultivation of vegetables, fruit, fiber crops, and trees for timber; it also included recipes for food, medicines, and wines as well as instructions on how to make such daily necessities as soap, glue, and dyes. The treatise stressed the importance of being guided by the weather and the type of soil available: "Following the appropriateness of the season, consider well the nature and conditions of the soil; then and only then, least labor will bring success. Rely on one's own idea and not on the orders of nature, then every effort will be futile."

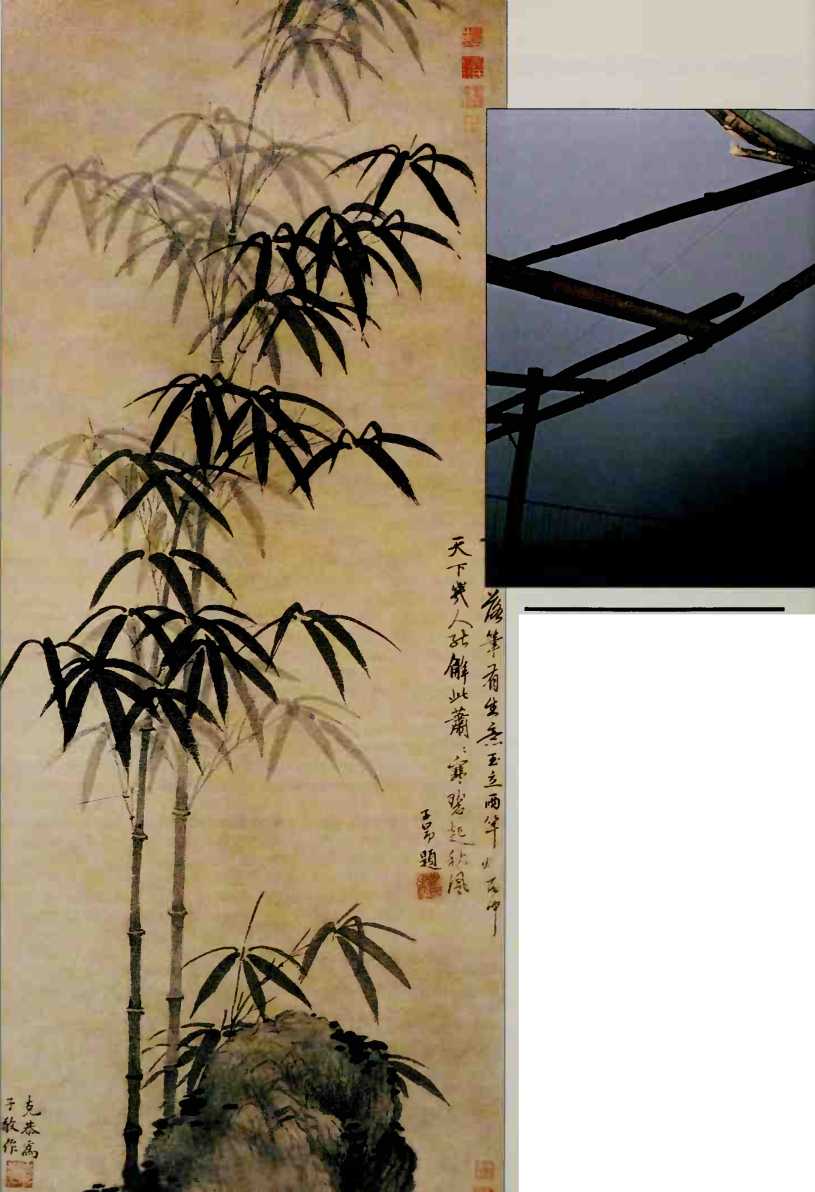

The tensile grace of bamboo stems—celebrated in the poem inscribed on this thirteenth-century ink drawing—is just one of the plant's virtues. Ubiquitous in China and widely grown in Southeast Asia and on the islands of the Indian and Pacific oceans, bamboo grows faster than any other plant, up to three feet a day. Cooked young shoots are eaten as vegetables; the pulp and fiber are processed to make paper; and the chemical compounds contained in some species are used in medicine. Bamboo is also used to make a vast range of domestic artifacts as well as to construct houses and build ships. Shown above, for example, is a section of a 755-foot-long bridge over the Min River in Sichuan province that is made entirely of bamboo.

Subsidiary crops have included corn, sweet potatoes, kaoliang—a type of sorghum—and peanuts. Tea bushes were grown on hillsides throughout South China, where variations in soil and climate in different districts produced distinctive flavors. Soybeans proved a rich source of protein and were also important in crop rotation to improve the soil. Hemp and ramie, a type of nettle, were the plants from which the clothes worn by most Chinese were made until the fourteenth century, when cotton was introduced from India and Southeast Asia.

For centuries, China's most profitable export was silk, which also—as a woven fabric or as wadding for padded garments—clothed the Chinese upper classes. Silk is derived from the silkworm moth larvae, which feed on the leaves of mulberry trees; the worms were domesticated at least 3,000 years ago, and China enjoyed a monopoly on the production of silk until the middle of the sixth century AD, when two Persian monks returning from China smuggled some moth eggs and mulberry seeds into Byzantium. Although modern instruments such as humidity gauges have made it easier to control the environment in which silkworms are raised, the process has remained largely unchanged. The eggs of the silkworm moths are either exposed to harsh weather or dipped in brine to kill off the weaker specimens. Upon hatching, the larvae are fed constantly for about one month on mulberry leaves; during this time, they surround themselves with cocoons of a delicate fiber, itself produced by liquid secretions that harden on contact with the air. When the larvae finish spinning their cocoons, they are plunged into boiling water, which kills the new moth and loosens the fiber. Almost 3,000 feet of thread can be reeled from each cocoon.

Because of the reliance on land for cultivation, only marginal terrain was devoted to grazing, and very little grain was expended on animal feed. Animals that could be fed on household scraps, or that could scavenge for themselves, such as pigs and poultry, were the livestock most commonly raised for food. Water buffalo proved ideal for pulling plows in the warm, damp conditions of the south, but their ownership was beyond the means of most farmers. Limited numbers of horses and mules were used for transport; usually, it was cheaper for humans to haul or carry goods.

A similar situation prevailed in India, where a vegetarian diet was the norm for the vast majority of the population. Indeed, for adherents of Buddhism and Jainism in India, vegetarianism was not just a necessity but an expression of virtue; According to the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, even an insect might harbor what had been and could again become a human soul and should, therefore, not be killed. In India, however, more use was made of dairy products, especially ghee—boiled and clarified butter—which became an essential cooking medium. Vegetables or lentils were cooked in ghee, flavored with spices, and then diluted with coconut milk to make a curry sauce that turned a bowl of rice into a substantial meal.

The scarcity of meat did not restrict the potential variety of the Chinese diet. A poem written in the second century BC celebrated a banquet that included pigeon, goose, chicken, oriole, roast crane, magpie, bream, turtle, pickled pork, dog cooked in bitter herbs, five varieties of grain, and four kinds of wine. This was hardly everyday fare, but for centuries, the filling staples eaten by the ordinary Chinese have been enlivened by a combination of less copious dishes based on vegetables, eggs, or meat. The greater the profusion of the latter, the more luxurious the meal.

Traditions of local cuisine were established that closely reflected the geography and consequently the produce of each region. In the grasslands of Mongolia, wheat bread is staple, and meat, particularly lamb and mutton, is plentiful; dairy produce is also popular. In the time of the Tang dynasty, from the seventh to the tenth century, the taste for milk was widespread, but most Chinese today find it repulsive. The northern Chinese eat quantities of steamed bread, wheat noodles, and stuffed dumplings. Sichuanese cooking is characterized by the liberal use of chilies, which were introduced from Central America in the sixteenth century; in the Yangtze Delta, fish is important, and sweet flavors are popular. Ingredients are often cut into matchstick-size shreds and are usually cooked quickly at high temperatures—probably because of the shortage of firewood for fuel.

Far from being the parochial customs of isolated provinces, local traditions of agriculture and cuisine had by the fourteenth century become distinctive strands woven into a huge and productive society. Following the introduction of the fastmaturing Champa strain of rice from Vietnam in the eleventh century, which ripened in one-third less time than the native plant, the land could be made to yield two or three harvests each year. Yields were also improved by the careful preparation and conservation of soil. Transportation benefited from paved roads and the use of locks in a spreading network of canals, and a nationwide system of customs houses levied tariffs on goods as they were moved around. The growth of markets stimulated trade both within and among China's three main economic regions—the north, the lower Yangtze Valley, and the Sichuan basin—and opened up a number of specialized occupations to the rural peasantry, including forestry, papermaking, and weaving.

In other fields also, China's technological achievements during the period known in Europe as the Middle Ages were vastly superior to those developed in the West. Machines for reeling silk and spinning hemp speeded the manufacture of clothing. Doctors learned to diagnose diseases with a new accuracy. Coal was used in the smelting of iron ore; gunpowder revolutionized warfare; and mathematics and astronomy flourished. While visiting China at the end of the thirteenth century, the Venetian traveler Marco Polo was filled with awe at the bustling, teeming cities and the productive countryside. "Indeed it is scarcely possible to set down in writing the magnificence of this province," he declared; and of the city of Hangzhou, he wrote that "anyone seeing such a multitude would believe it a stark impossibility that food could be found to fill so many mouths."

For all governments of eastern and southern Asia, the problems of balancing the food supply with a growing population have been a pressing concern—not the least because a hungry populace can quickly become an army of rebellion. The shelves of the Han imperial library were filled with scrolls on agriculture and medicine as well as on astronomy, mathematics, and military matters. Very soon after the invention of printing in China in the ninth century AD, treatises containing advice on husbandry began to circulate widely. But only a tiny proportion of the population was able to read, and the spread of information could have only a limited effect. The most direct means of controlling production, as rulers soon realized, was through control of the land itself and the people who worked it.

Many forms of control were attempted. In northern China in the fourth century, for example, land was allotted to individuals for use during their lifetime, with provision for officials to receive larger portions according to their rank. But this system proved incompatible with the wet-field farming of the Yangtze Valley, as it failed to ensure that those who made the great investment of collaborative labor needed for irrigated farming to succeed were the ones who reaped the benefits. Other systems of land

In Papua New Guinea, the heads of butchered pigs are impaled above stones that are being heated to cook their flesh. For certain peoples in New Guinea and the islands of the South Pacific, Ihe pig is a holy animal that must be sacrificed to their ancestors, and once or twice in a generation, these peoples slaughter and eat the majority of their herds in a ritual feast. The roots of the practice may lie in Ihe need to regulate Ihe numbers of livestock so that they do not encroach on growing crops.

Tenure varied from region to region. In some places, such as the mountainous regions of today's province of Zhejiang, peasants were usually independent; in others, they were virtually slaves, working under the close supervision of an overseer; in areas ravaged by warfare or underpopulated for other reasons, the government often took direct control. In general, the more productive the land, the more likely it was to be owned by landlords and worked by tenants.

Landlords clearly exercised immense control over the lives and fortunes of others, and the Song dynasty that ruled from AD 960 to 1279 developed a system of coopting members of this ruling class into the administration of the state. The wealthiest people in a village were required in turn to perform such duties as the collection of taxes, supervision of waterworks, arbitration of disputes, road maintenance, and when necessary, the distribution of famine relief. But even this system did not solve the perennial problems of government—for whenever the state devolved responsibilities upon local elites, they would build on their position of power to challenge imperial authority. Many took advantage of their status to evade their taxes, passing the burden on, through their managers and agents, to those in their sway.

From the fifteenth century onward, the administration of China was carried out in large measure by a class of educated scholar-gentry who owed their position to success in the civil service examination system rather than to hereditary wealth. The growth of this meritocracy, coupled with the development of a market economy in the countryside, led to a decline in the power of wealthy landowners— and the responsibilities of working the land increasingly fell to those most directly concerned, the peasant families who made up by far the majority of the population.

In some societies, animals deemed sacred are eaten; in others, their flesh is forbidden for the same reason. As the examples shown here and overleaf illustrate, attitudes toward food obey no universal pattern, often because they have evolved in response to very specific local conditions.

When early farmers discovered that a particular meat caused illness, they avoided it. When the raising of a certain animal conflicted with their essential way of life— pigs, for example, which yield no milk, are less vital to pastoralists than sheep or goats—they learned to do without its meat, however delicious. Over time, these customary habits frequently developed into religious prescriptions, which were themselves reinforced by other factors—the need to standardize behavior to maintain the social order, or to give expression to a people's sense of their unique identity.

OF DIET

The rural family household was the essential building block of the edifice that was the Chinese imperial state. The family was seen as reaching both backward and forward in time, encompassing both ancestors and unborn descendants; it was also linked by a network of kin groups, lineages and clans to other family units occupying a wide geographical area. In general, households were large, as the prosperity of each family depended on the number of able-bodied members it could put to work. On the other hand, because land was not inherited by the firstborn exclusively, farms were divided into increasingly smaller parcels, and most were less than five acres.

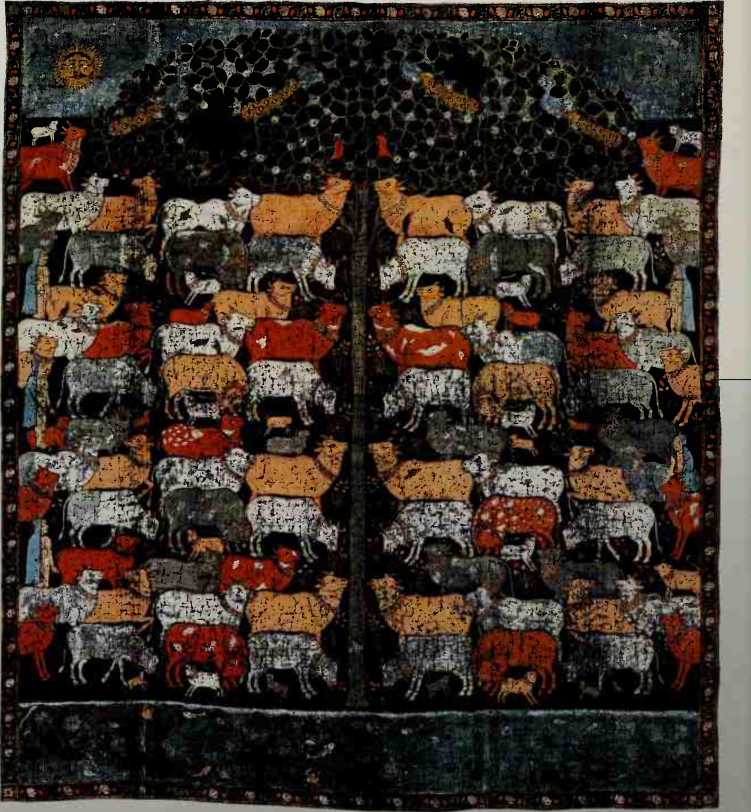

An eighteenth-century cotton wall hanging from northwest India depicts cows grazing and calves suckling in a paradisiacal landscape. The sacred status of cattle in Hinduism and the ban on eating their flesh probably derived from the value placed on living animals in agriculture. Cattle are still used for drawing plows in most of India, while their dung is used as a fertilizer and is the only cooking fuel for nine out of len rural households.

The life of rural families was far from comfortable. In the sixteenth century, a local historian in Tancheng county in the province of Shandong, northeastern China, reported that although in a normal twelve-year cycle there were equal periods of abundance and scarcity, his own district was stricken by famine every year. When a new magistrate arrived in the county in 1670, the local residents reported that their land had long been “destitute and ravaged. For thirty years now, our fields have lain under floodwater or weeds; we still cannot bear to speak of the devastation." Floods and locust plagues had repeatedly destroyed their harvests, and thousands had been killed by gangs of bandits. "On top of all this came the famine of 1665; and after the earthquake of 1668, not a single ear of grain was harvested, over half the people were dying of starvation, their homes were all destroyed, and ten thousand men and women were crushed to death in the ruins."

In better times, the land yielded sufficient food, but not without continuous work. As soon as the winter snows had melted, the fields in Tancheng county in which winter wheat was not growing were turned and spread with animal and human fertilizer. In early May, this land was plowed and sown with millet and kaoliang; the earth was leveled with a wooden harrow and compacted either with a roller or by treading feet. As the crops grew, the fields were repeatedly weeded and the soil tamped down around the shoots. The winter wheat was harvested in June, and the land where it had grown was plowed and sown with soybeans. In August, the millet and kaoliang were harvested and carried to the threshing ground, and in October, the winter wheat was planted. Besides these staple crops, the farmers also grew vegetables such as turnips, cabbage, onions, celery, eggplant, and garlic.

From the sale of their produce, the farmers had to pay taxes to both the local and central governments. In addition to taxes on land and agricultural production, there were levies on sales of a range of items including salt, livestock, wine, and cotton goods, and the government could buy produce from farmers at below-cost prices. All adult males were liable to be drafted for corvee labor—to build dikes, irrigation

A fifleenIh-cenlurY Italian illustration (rom a Hebrew law code shows the ritual slaughter of fowl and oxen. while many of the Jewish dietary laws laid down in the book of Leviticus may have evolved because they were hygienically beneficial, others have more complex origins. The pig, for example, was seen by early Middle Easlern pastoralisis as a very different kind of animal from the sheep, goats, cattle, and camels that constituted their herds; and it was possibly because the pig did not fit the perceived norm that its flesh was outlawed.

Canals, and other public works—or else had to pay an extra tax in lieu of labor. Many households were required to furnish a militiaman in times of emergency.

Unsophisticated though it may seem in comparison with modern Western agriculture, which made increasing use of technology and modern science from the eighteenth century onward, it was this labor-intensive system based on the tilling of small plots by family units that enabled China to support its growing population into the twentieth century. The very size of the work force was one factor that encouraged such conservatism: Where labor was cheap and plentiful, the introduction of machinery that saved on man power was unnecessary, and indeed would have created new social problems by throwing thousands if not millions out of work.

Nevertheless, the growing population did place increasing pressure on agricultural resources. In 1740, the emperor noted that "the population is constantly increasing, while the land does not become any more extensive," and he urged his subjects to cultivate every available plot of ground "at the tops of the mountains or at the corners of the land." At the end of the first millennium, China's population was around 100 million; by 1850, this number had risen to 450 million. In the twentieth century, it became apparent that the needs of the population could no longer be met without radical social reforms and technological development.

These became the urgent priorities of the Communist government after the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, and they were acted upon with a speed and ruthlessness that turned Chinese society upside down. Land reforms completed in 1952 confiscated the holdings of landlords—two million of whom were killed in the process—and redistributed their land to poor peasants. There then began a program of collectivization, modeled on the experience of the Soviet Union in the 1920s, which involved the elimination of private ownership of land. By 1957, it is estimated that 96 percent of the rural population was incorporated into agricultural cooperatives in which all equipment, animals, and labor were pooled for the common good. The cooperatives were in turn organized into self-sufficient administrative units known as communes, each comprising an average of 5,000 households.

Such drastic changes could never have taken place had not the Chinese been accustomed for centuries to a hierarchical society in which obedience to one's elders and those in authority was not just a social virtue but a way of life. But in their attempts to substitute the state for the family as the focus of loyalty for all Chinese, the government created unexpected disturbances. Reverence for the past had for centuries been a mainstay of social stability: Evident in the chronicles of past dynasties painstakingly compiled by court historians and in the works of artists and writers who adhered to ancient traditions, this reverence's most basic expression was the ancestor worship of individual families. By seeking to eradicate all past models, the Communist leaders ensured that the birth of the new order was accompanied by confusion and disorientation.

In addition, the government's policies were often based on information that did not accord with reality. Following the establishment of the rural communes, the government came to believe, in line with inflated production figures supplied by ambitious commune leaders, that China had a massive surplus of grain, and it ordered a reduction in the area of land given over to rice growing. In fact, during the years between 1958 and 1961, China was suffering probably the worst famine in its history, causing the deaths of as many as 30 million people.

Subsequent reforms, based more on a realistic assessment of China's needs than on

In this sixteenth-century Japanese garden—a frozen encounter between resistant nature and the human urge to arrange and transform—the forms of mountains and rivers are tamed and reflected in a cultural mirror. Introduced from China in the seventh century, the art of creating these austere and compressed landscapes accorded well with the nature veneration of the ancient Japanese Shinto religion. After Zen Buddhism came to Japan in the early thirteenth century, again from China, such gardens were created for Buddhist temples as ideal settings to foster meditation.

Ideological rigor, improved the lot of the long-suffering peasantry. Between 1965 and 1975, it is claimed that the area of irrigated farmland was increased by one-third. In the 1980s, individual peasant households again became the basic unit of production, and they were permitted to sell surplus produce at rural markets. Overall, the food supply per person rose after the Communists came to power.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the government instituted a program designed to reduce population growth. Families were officially forbidden to have more than one child and lost welfare benefits if they exceeded this limit. Although the program represented a degree of state interference in private life that would have been unacceptable in the Western world, it was the logical response to the inescapable fact that China's arable land—only 11 percent of its total territory—could not support an ever-growing population.

Other countries around the world looked to China with keen interest, for in the 1980s there was a growing awareness that the problems of food supply were present

On a global scale. In 1990, it was estimated that 700 million people in the Southern Hemisphere were without adequate food—or in other words, for every affluent person in the north, another was close to starvation in the south.

Apart from limiting the size of families—and in most countries of Asia and Africa as well as in rural districts of China itself, effective birth-control programs have so far proved almost impossible to implement—only the application of advanced scientific procedures to crop growing could alleviate the scale of world hunger. In the nineteenth century, the Western world solved its own food crisis by the mechanization of agriculture and the development of refrigeration, canning, and improved transportation. In the late twentieth century, biotechnology—the range of disciplines associated with the genetic manipulation of living organisms—appeared to offer hope of similar success. For example, crops that have built-in resistance to pests—and therefore do not require the use of chemical pesticides—could greatly reduce the loss in production caused by weeds and disease, which at present destroy as much as 40 percent of the world's crops. But all such developments are vulnerable to political and economic pressures. One variety of hybrid rice now grown in over one-third of China's approximately 80 million acres of rice paddies has increased harvests by 25 percent—but, determined to profit from this advance, China sold rights for the exclusive sale of the seed to two American companies, thereby limiting the number of poorer countries that could benefit.

Some Chinese hybrid seeds have proved unsuitable for cultivation in Western countries because they require so much labor. The plants made few seeds, and without a large and cheap work force to fertilize them by hand, they offered scant profits. But this very obstacle demonstrates that the agriculture of China and other Asian countries, often viewed by outsiders in the past as backward and inefficient, has become a model of increasing relevance to other countries whose massive and growing populations appear to handicap all plans for a sustainable future. Laborintensive, sparing of natural resources, and with a strong emphasis on grains and vegetables, the agriculture of Asia is greatly productive in terms of yield per unit of land. Not the least of its exemplary characteristics has been the degree of communal effort necessary for survival. _

In Africa, India, and North America, there are gold mines that extend so deep into the earth's crust their walls are hot. Without air conditioning, the miners would die. When they return to the surface, in elevators that travel slowly so that their ears do not pop, their faces are unnaturally pale.

RICHES

Humans are not built to burrow under the surface of the planet, but from the time they first began to fashion sharp tools and bright ornaments, they have devised methods of extracting the riches embedded in the earth. Flint was quarried to make blades beginning around 40,000 BC. Copper was mined by the ancient Egyptians, and by Roman times, the metal ores extracted from both surface and underground sources included iron, gold, silver, lead, tin, and zinc. The Industrial Revolution accelerated demand for coal and, later, for other fossil fuels such as petroleum and natural gas, all formed by the decomposition of prehistoric organisms.

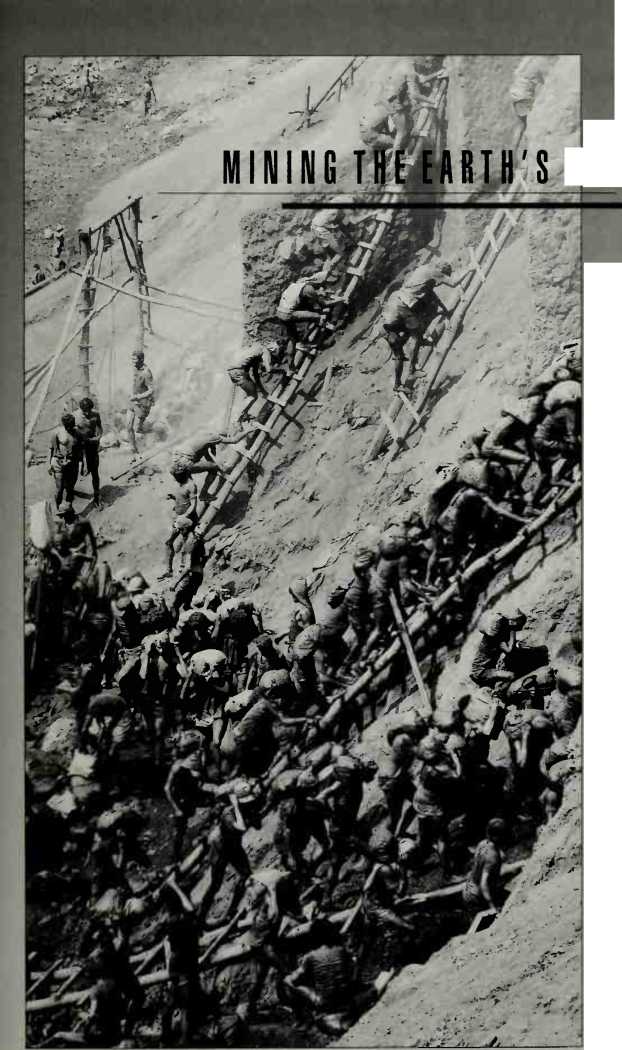

The rate of material progress generated by the earth's minerals has been matched by the increasing impact of mining on the environment. The most conspicuous effects are those of surface mines—both those worked by manual labor, as shown in the photograph on the left of a gold mine in Brazil in the 19B0s, and those exploited by mechanical excavators, the largest of which can remove 6.3 million cubic feet of coal per day. But the impact of underground mines is no less severe: They can cause subsidence, contaminate water sources, and despoil the surrounding land. The furnaces for smelting silver ore from Roman mines in Spain, for example, consumed 500 million trees, clearing an area of almost 7,000 square miles. The safe disposal of radioactive waste from the mining and processing of uranium and plutonium for nuclear power now challenges the technology that, as shown on the following pages, has enabled humans to penetrate ever farther from their given habitat.

A day tablet of the sixth century 8C (right) depicts Creek miners quarrying for clay. A ladder is propped against the side of the pit; the hanging amphora probably contained refreshment. On the far right, a fifteenth-century German woodcut shows a natural seepage of petroleum being collected in a jug. Oil was believed to cure many ailments: ''He who pants with a cold or cough of long standing, let him rub the chest with it, and it helps," declared a contemporary pamphlet.

In tunnels dug beneath the lapanese island of Sado, where gold was discovered around 1600, miners in a nineteenth-century woodcut by Hiroshige work by the light of burning wicks in vessels of oil.

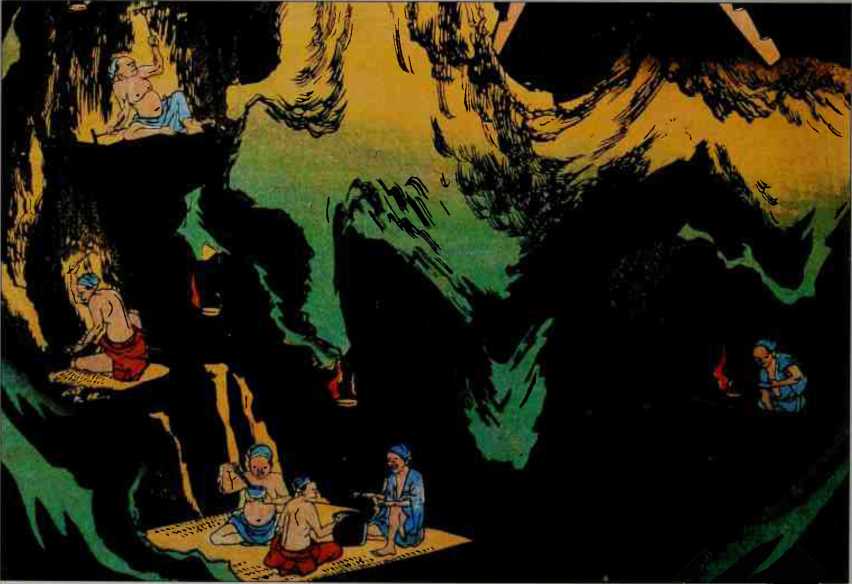

Although most mines were dug and worked by muscle power until the nineteenth century, the impact of picks and shovels was by no means negligible. In Austria during the second millennium BC, there were as many as 500 copper mines with timber-lined underground tunnels in the region around present-day Salzburg, while flint was mined in England from galleries supported by pillars of unworked rock.

In addition to human and animal muscles, the most long-established and enduring source of energy harnessed for surface mines was water, which was employed by the Romans to break up banks of loose soil. Beginning in 1853, the use of high-pressure waterjets during the California gold rush altered the contours of the land, shaving soil from the hillsides and building up new hills out of the debris.

A German walercolor dal-ing from 1480 depicts an underground mayhem of pick-wielding miners. Because of the value of Ihe iron ore they exiracled, German miners were among Ihe most privileged of medieval workers: Many were exempt from taxes and military service.

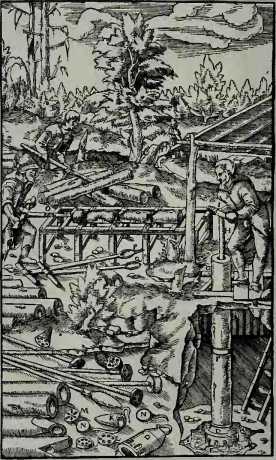

Sixteenth-century woodcuts from a treatise by German mineralogist Georgius Agricola show drainage and ventilation: Above, a man works the piston of a suction pump to raise water; above right, two men turn cranks to send air underground.

Tn this sliver mine in Lorraine, depicted in a sixteenth-century German engraving, picks, hammers, and wedges remain the miners' essential tools, but the removal of mined ore has been streamlined by the use of manual winches and wheeled carts in vertical shafts and level, horizontal tunnels.

A steam engine (right) at an early-nineteenth-century pithead in England, feeding off the hemispherical boiler under the smokestack, powers the gear that raised and lowered both miners and coal. On the right, a loaded cart stands on a weighbridge.

In medieval Europe, machines powered by humans, animals, or streams were devised to bail water from flooded shafts and raise minerals from ever-lengthening tunnels. To mine iron ore—used for tools, weapons, and armor—hammers and wedges were supplemented by gunpowder and by fires set to fracture a rockface. Dwindling supplies of wood for the smelting of ores led to an increased use of coal, especially in England and Wales, whose output by 1700 amounted to five times that of the rest of the world. The development of steam power by the Scottish engineer James Watt around 1765 provided a new source of energy with which to pump out floodwater, and after the introduction of steam-driven rotary and piston drills in the early nineteenth century, to dig ever deeper.

World History

World History