It might have been Hopewell, or it might have been a larger regional phenomenon, but one cannot escape the fact that the Native American population from southern Canada to Florida began to display a Hopewell-styled culture of grand ceremonialism in which large earthwork projects were made, all of which formed an astonishingly complex and widespread social and religious continuum. This occurred before the arrival of corn around 800 ce.31 Ceremonialism even went as far as South Dakota, where between 500 and 800 ce a mound-building culture set up its ancestor mounds around the watershed of the Big Sioux River and Big Stone Lake, although other sites have also been excavated throughout eastern South Dakota.

The most impressive sites are in the south. A site in Tennessee, for example, Pinson Mounds, rose to the level of a ceremonial center, perhaps because of its proximity to a mining site for mica in North Carolina. Mica, because of its shiny surface, was sacred to shamanistic rituals and was used, where found, in many parts of the Americas, even among the Olmecs in Mexico. Pinson Mounds, located about 16 kilometers south of today’s city of Jackson, overlooked the south bank of the Forked Deer River. It had at least twelve mounds, several earthworks, and a large circular enclosure that was built up from 200 bce to 475 ce. Among its larger mounds is one that is 22 meters in height and rectangular in plan with the rounded corners aligned toward the cardinal directions. The mounds were originally surfaced with yellow sand.

Similarly impressive was the site known as Marksville in Louisiana. It consisted of at least two earthen embankments enclosing seven mounds, all built between 1 and 400 ce. The huge 40-acre site was defined by a 3-meter-high, 1-kilometer-long, C-shaped embankment that opens onto a large flood marsh on the western side of the Mississippi River. The northernmost mound was 100 meters in diameter and 4 meters high. Built in a single act of construction, it served as a staging area for events. Nearby was an ancestor mound where at least thirty-six men, women, and children were buried. At its core was a large square burial platform. The other mounds have unknown purposes. It is clear that Marksville was a ceremonial center where people from nearby villages gathered for important social and religious events. Dozens of small enclosures and mounds dot the area around the enclosure.

And if we go even farther south to southern Florida, we see ancestor mounds there as well. Leslie Mound in the Suwannee Valley was built and used in the following manner. First a circular area of ground, 26 meters in diameter, was cleaned of grass and a 10-centimeter-high layer of clean soil was laid down. On top of that a low 10-meter-long platform mound was constructed. Bundled bones and crania removed from a charnel house where the body had decomposed were then placed on the mound surface, where they were then covered with a second mound about a meter high.32

Ceremonial roads were also built. One such road connected the St. Johns River to the Keys and was described and drawn in 1853.33 The author noted that the roads, in typical fashion, tended to connect a mound with a body of water like a lake or lagoon. The Calusa made them in the form of canals, 10 meters in width and in some cases more than 10 kilometers long.34 There are—or were—so many impressive sites in Florida that it must have constituted a regional phenomenon on par with the Hopewell, even though it came about much later, beginning around 200 ce and reaching its height around 1400. Particularly enigmatic is Fort Center in the savanna west of Lake Okeechobee. It had a large circular mound directly tangent on Fisheating Creek. To the east of that was a mortuary complex with what seems to have been a burial pond, and farther east were three ceremonial roads ending in mounds. A large wooden ceremonial bird was found intact in the pond.

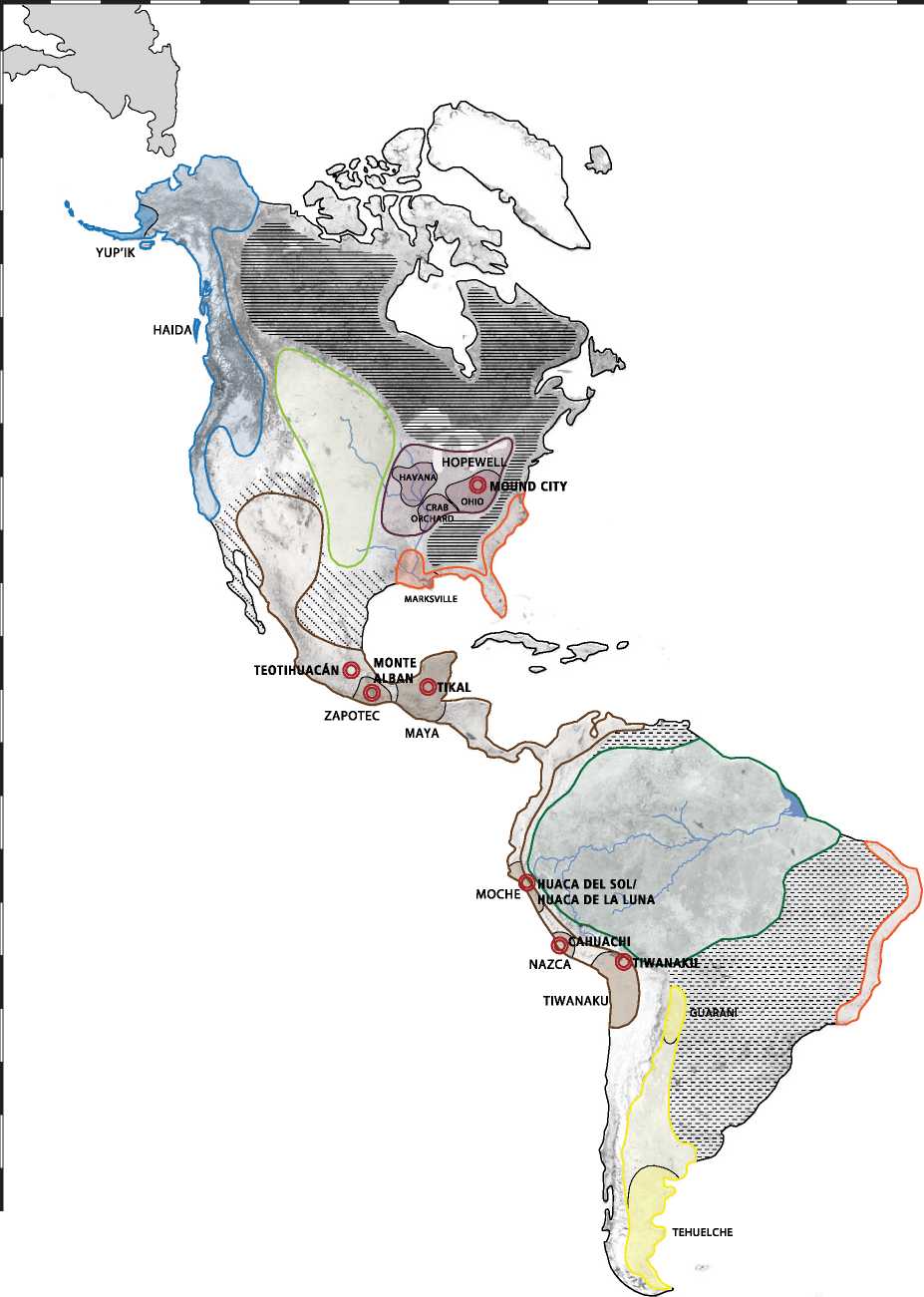

Except for Florida, the Hopewell ceremonial culture, along with the social, economic, and religious relationships it embodied, came to a gradual end about 400 ce. The elaborate trade network dissipated and was replaced by more regionally focused and for a time much simpler social arrangements. The reasons for this are much debated, but there is no indication of large-scale warfare. Though mound construction waned, the associated rituals and their tribal and clan meanings did not perish. They would soon be revived, in fact, and reach even greater heights, but under difierent auspices that can be summarized in the word “agriculture” (Figure 6.27).

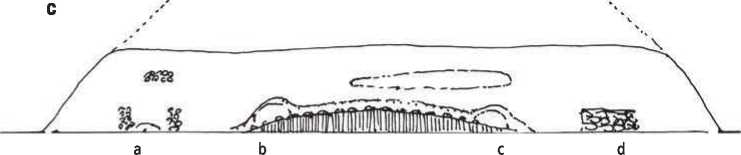

Figure 6.26a, b, c: North Benton Mound, North Benton, Ohio: (a) map; (b) plan; (c) section. Source: Mark Jarzombek/WiHis H. Magrath, “The North Benton Mound: A Hopewell Site in Ohio,” American Antiquity 11 (July 1945): 41

Figure 6.27: The Americas. Source: Michael Kubo

1. See Kenneth E. Sassaman, “Poverty Point as Structure, Event, Process,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 12, no. 4 (December 2005): 335-364.

2. Vernon James Knight, Jr., “Symbolism of Mississippian Mounds,” in Powhatan’s Mantle, Indians in the Colonial Southeast, eds. Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, and Tom Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006): 421-434.

3. James A. Goss, “Traditional Cosmology, Ecology and Language of the Ute Indians,” Ute Indian Arts and Culture: From Prehistory to the New Millennium, Edited by William Wroth (Colorado Springs: Taylor Museum of the Colorado Fine Arts Center, 2000): 47-49.

4. John Thomas Scharf, History of Saint Louis City and County: From the Earliest Periods to the Present. Volume 1. (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883): 98.

5. Henry M. Brackenridge, Views of Louisiana (Baltimore: Schaffer and Maund, 1817): 172-174. Brackenridge (1786-1871) was a writer, lawyer, judge, and Congressman from Pennsylvania.

6. Elsa M. Redmon, “In War and Peace, Alternative Paths to Centralized Leadership,” Chiefdoms and Chieftancy in the Americas. Edited by Elsa M. Redmond (Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 1998): 83-84.

7. Sam D. Gill, Songs of Life: An Introduction to Navajo Religious Culture (Leiden: Brill, 1979): 3.

8. Quoted in Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton, Native American Architecture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989): 109.

9. Amelia Bell Walker, “Tribal Towns, Stomp Grounds and Land: Oklahoma Creeks After Removal,” Chicago Anthropological Exchange 14 (1981): 50-69.

10. Joe W. Saunders et al., “Watson Brake, A Middle Archaic Mound Complex in Northeast Louisiana,” American Antiquity 70, no. 4 (October 2005): 631-668.

11. Bruce D. Smith, “The Archaeology of the Southeastern United States: From Dalton to de Soto, 10,500-500 BP,” in Advances in World Archaeology. Volume 5, eds. Fred Wendorf and Angela E. Close (London: Academic Press, 1986): 32. 16. Vernon James Knight, Jr., “Symbolism of Mississippian Mounds,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, eds. Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, and Tom Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006): 421-434.

12. Vernon James Knight, Jr., “Symbolism of Mississippian Mounds,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, eds. Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, and Tom Hatley (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006): 421-434.

13. Rebecca Saunders and Michael Russ, “The Fig Island Ring Complex (38CH42): Coastal Adaptation and the Question of Ring Function in the Late Archaic” (Report prepared for the South Carolina Department of Archives and History under grant #45-01-16441, August 5, 2002). Available online at Www. nps. gov/seac/shellrings/fig_web. pdf (accessed August 19, 2011).

14. Victor D. Thompson, “Questioning Complexity: The Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of Sapelo Island, Georgia” (PhD Dissertation, University of Kentucky, 2006). V. D. Thompson and C. F. T. Andrus, “Evaluating Mobility, Monumentality, and Feasting at the Sapelo Island Shell Ring Complex,” American Antiquity 76, no. 2 (April 1, 2011): 315-344.

15. Michael Russo, Gregory Heide, and Vicki Rolland, “The Guana Shell Ring,” (Report submitted to The Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources, July 2002): 1-22. Available online at Www. nps. gov/seac/shellrings/Guana_pp1-22.pdf (accessed August 19, 2011).

16. Robin C. Brown, Florida’s First People, 12,000 Years of Human History (Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 1994): 115.

17. W John and H. Hann, Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003): 35-36.

18. Henry R. Schoolcraft, Sacred Origin of Tobacco (Philadelphia: 1851). See also Arthur P. Rose, An Illustrated History of the Counties of Rock and Pipestone, Minnesota (Luverne, MN: Northern History Publishing Co., 1911): 248.

19. Jimmy Railey, “Woodland Settlement Trends and Symbolic Architecture in the Kentucky Bluegrass,” in The Human Landscape in Kentucky’s Past, eds. Charles Stout and Christine Hensley (Frankfort: Kentucky Heritage Council, 1991): 30-39.

20. Don W. Dragoo, Mounds for the Dead: An Analysis of the Adena Culture (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 1989); Michael Striker, “Ancestor Veneration as a Component of House Identity Formation in the Early Woodland Period,” paper presented at the 6th World Archaeological Congress, Dublin, June 2008. Available online at Www. nku. edu/~strikerm/Ancestors. pdf (accessed August 17, 2011).

21. Nicole I. Stump et al., “A Preliminary GIS Analysis of Hocking Valley Archaic and Woodland Settlement Trends,” in The Emergence of the Moundbuilders: The Archaeology of Tribal Societies in Southeastern Ohio, eds. Elliot M. Abrams and AnnCorinne Freter (Athens, OH: University of Ohio Press, 2005): 125-138.

22. William S. Webb and Charles E. Snow, The Adena People (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1974). William A. Ritchie and Don W Dragoo, “The Eastern Dispersal of Adena,” American Antiquity 25, no. 1 (July 1959): 43-50.

23. A quote from H. M. Brackenridge cited in John Thomas Scharf, History of Saint Louis City and County: From the Earliest Periods to the Present. Volume 1. (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883): 98.

24. John Haywood, The Natural and Aboriginal History of Tennessee: Up to the First Settlements There by the White People, in the Year 1768 (Nashville: George Wilson, 1823): 397.

25. James Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees (Kessinger Publications, 2006), 396. Originally published as Myths of the Cherokee (1900).

26. See the study by William F. Romain, Mysteries of the Hopewell: Astronomers, Geometers, and Magicians of the Eastern Woodlands (Akron: The University of Akron Press, 2000): 65-100.

27. Jane E. Buikstra, Douglas K. Charles, and Gordon F. M. Rakita, Staging Ritual: Hopewell Ceremonialism at the Mound House Site (Kampsville, IL: Center for American Archaeology, 1998): 84-90.

28. Ake Hultzkrantz, The Religions of the American Indians, trans. Monica Setterwall (Berkeley: Berkeley University Press, 1979): 135.

29. Charles Hudson, The Southeastern Indians (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1976): 122.

30. Willis H. Magrath, “The North Benton Mound: A Hopewell Site in Ohio,” American Antiquity 11, no. 1 (July 1945): 40-46.

31. The archaeological term “Mississippi Culture” usually refers to those places built after the arrival of corn around 800. This period is discussed in the literature as the “Middle Woodland Period” (1-500 ce). I would prefer to think of the period as the Ceremonialist Period, divided into its precorn and post-corn phases. The term “Woodland,” coined in the 1930s, favors the arrival of corn and its associated agricultural requirements. This tendency to elevate the agricultural societies over the “hunter/gatherer” societies is in this case quite obsolete.

32. Jerald T. Milanich, The Timucua (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996): 36.

33. William Bartram, Travels and Other Writings (New York: Library of America, 1996).

34. Randolph J. Widmer, The Evolution of the Calusa: A Nonagricultural Chiefdom on the Southwest Florida Coast (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988): 6.

World History

World History