Why were wild animals hunted in the Celtic Iron Age? The faunal evidence from bone assemblages indicates that wild species formed an extremely small part of the diet of these communities, so food was not a primary reason (chapter 2). There is some evidence for butchery, so at least some of the herbivores were eaten. Other reasons for hunting included the desire for fur, the need to protect farmland from the destructive activities of such animals as deer, and finally - and this is likely to have been the primary reason - for sport.

The hunting of the larger animals - like stags and boars - may well have been a sporting pastime for the aristocratic elite, who would have seen hunting as a simulation of and practice for warfare. This may partly account for the small number of such beasts represented in the faunal assemblages of Iron Age settlement sites and the absence of butchery marks on boar bones.67 Barry Cunliffe says that if hunting took place at all at Danebury, it must have been merely for sport, since wild-animal bones are so rare.68 Arrian, writing in the second century AD, speaks of hunting as a sport for

Figure 3.7 Bronze figurine of crow or raven from the Romano-Celtic sanctuary of Woodeaton, Oxfordshire. Betty Naggar.

The wealthy69 and refers to hunting among the Celts as a noble pleasure rather than a livelihood, though he says that for the Celts hunting was not just a noble pastime but a daily exercise of skill and courage, involving several levels of society.70 The idea of hunting as an activity of the elite would fit in well with the hunting methods employed by the Celts, which involved horses (expensive creatures to maintain) and specialized hunting-dogs. Weapons of war could indeed be used with equal effect in hunting: Strabo remarks that the Celts used a spear-like stick both for hunting birds and in war.71

There is evidence both from classical writers and from archaeology that wild animals were hunted for their skins (see also chapter 2). Diodorus Siculus72 speaks of the use of wild beasts' pelts by the Celts for bedding and of wolfskins for covering house floors. The young late Iron Age chieftain whose remains were interred in a rich grave at Welwyn (Herts.) was laid on a bearskin.73 The earlier Iron Age Hallstatt prince buried in the fantastically rich barrow at Hochdorf in Germany was laid to rest on a bronze couch covered in a badgerskin.74 Wild animals are poorly represented in the skinning debris (tail and paw bones) of Gaulish sites, but there is some evidence for wolf, badger, fox, polecat and stoat. Though bears were plentiful during this period, their skeletons are not generally

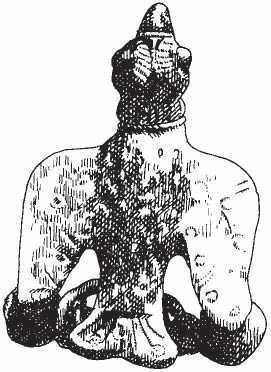

Figure 3.8 Stone image of a man (rear view shown) possibly wearing an animal pelt, Cirencester, Gloucestershire. Betty Naggar.

Found in the faunal assemblages: their skins must therefore have been removed away from the settlements, if they were used at all.75 We have seen (pp. 44-5) that occasionally the teeth of bear and wolf were used as ornaments and it is possible that such creatures were hunted specifically to provide decoration for the dead. Foxes may have been hunted for their pelts, as is shown by Lindow Man's fox-fur bracelet. But the fox remains at the sanctuaries of Mirebeau and Ribemont indicate from butchery marks on the bones76 that foxes were sometimes consumed. The strange deposit of red deer and twelve foxes in a pit at Winklebury in Hampshire77 must surely indicate the hunting of these creatures for a primarily ritual purpose (see chapter 5). At Danebury, there is evidence that both badgers and foxes were trapped for their fur.78 Interestingly, at the settlement of Villeneuve-Saint-Germain, the tail and paw bones of animals (indicative of skinning) were found on a part of the site which was kept separate from the areas of food preparation.79 The small numbers of fur-bearing animals represented on Celtic sites probably does not reflect reality. Wolves, bears, badgers, foxes must all have been hunted with some frequency, but the skeletal evidence is rare, implying that there must have been many instances where skinning took place away from the settlements themselves, presumably at the kill-sites.

Wild and hunted food animals are relatively rare on Iron Age sites, such species being often represented by less than 5 per cent of all animal bones. We have seen that boars are not commonly found in the faunal material and that, if they do occur, the lack of cut-marks suggests they were not butchered and consumed on settlement sites. Of all the hunted animals, the hare seems to have been most popular, even though Caesar says that hares were not eaten in Britain.80 At Epiais-Rhus (Val d'Oise), the animals hunted for food were mainly hare, followed by roebuck, red deer, stag and boar. In the villages of Compiegne and in the settlements of the Somme region, again the hare was the wild animal most frequently consumed. Patrice Meniel81 makes the point that, although wild animals are few on northern Gaulish sites, they are none the less consistently present in small quantities on all the sites investigated. In Britain, at the Meare lake village (Som.),82 a wide range of wild resources was utilized, including boar and deer, marsh-birds and such fish as pike and eel. Wild game birds, like geese, swans and ducks, were also snared at Danebury.83 Generally speaking, there is little evidence that fish were commonly eaten in the Iron Age, though the rock art of Camonica Valley depicts the occasional fish being netted or harpooned.84 However, fish bones are fragile and are not readily preserved on archaeological sites. The unequivocal message conveyed by the archaeological evidence is that hunting was peripheral to the Iron Age economy and, in terms of food, served only to supplement and add variety to a meat diet whose requirements were generally met by farming.85 Interestingly, whilst there is a great deal of evidence of culinary sacrifices and ritual feasting which involved meat, evidence from many of the Celtic shrines - such as Gournay, Hayling Island and many others - suggests that wild beasts were not used at all.86

HUNTING METHODS The hunter's companions

Both classical commentators and iconography throw light on the way game was hunted by the Celts. There were different kinds of hunting: the peasant wishing to rid himself of pests threatening his crops would perhaps use dogs, traps and snares. The knight-hunter, maybe practising the art of war, would use swift horses and sometimes specially bred and trained dogs. The main method employed in the pursuit of large and fast game certainly involved horses and big, aggressive dogs. The best type of horse for long-distance endurance would be lean and tough.87 Thus the hunter could follow his prey on horseback over long distances. The use of horses in hunting is reflected iconographically: the seventh-century BC Strettweg cult-wagon carries bronze figurines of horsemen and foot-soldiers in the company of two stags, in a ritual hunting scene.88 The Iron Age rock art of the Camonica Valley includes scenes of mounted hunters in pursuit of or surrounding stags; other game, such as wild goats, were followed in a similar manner.89 A pot dated seventh to sixth-century BC from the Hungarian site of Sopron depicts a stag hunted by mounted spearsmen. The Camonica hunters are shown armed with spears and shields, just like warriors,90 and they often hunted in pairs. One representation is of a horseman, led by an armed servant, hunting with a long curved stick, rather like a hockey stick.91 This is especially interesting since Strabo alludes to the use the Celts made, when they were hunting birds, of a spear-like stick 'with a range greater than an arrow'.92 Strabo also comments on the use of bows and slings. The spear or lance was a weapon commonly used by huntsmen, especially on horseback. The second - or first-century BC bronze wagon-model from Merida in Spain depicts a spearman on horseback chasing a boar. He wears greaves like a soldier.93 According to Camonican iconography, the lance was the favourite weapon for despatching animals once they had been snared.94 If he was a rider, the hunter would probably have belonged to the upper echelons of society. So too, perhaps, would the falconers; there is a hint that falconry may have been employed in hunting during the La Tene Iron Age: bronze brooches from the Durrnberg hillfort in Austria (figure 3.10) depict birds of prey wearing collars.95 Certainly hawks were familiar to the Celts of the early vernacular legends; gifts exchanged between Pwyll, lord of Arberth, and Arawn, king of the Otherworld, in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, include horses, greyhounds and hawks.96

Dogs played an important part in hunting: Strabo97 refers to the export of British hunting-dogs to Rome. He describes them as small, rough-haired, strong, swift and keen-scented. The continued fame of British dogs is demonstrated by a later writer, a Roman poet of Carthaginian origin, Marcus Aurelius Olympius Nemesianus, who wrote a poem called the 'Cynegetica' (The Hunt') in about AD 283-84. He includes these lines in the poem: 'Besides the dogs bred in Sparta and Molossus, you should also raise the breed which comes from Britain, because this dog is fast and good for our hunting.'98 Claudian describes British dogs as strong enough to break the necks of great

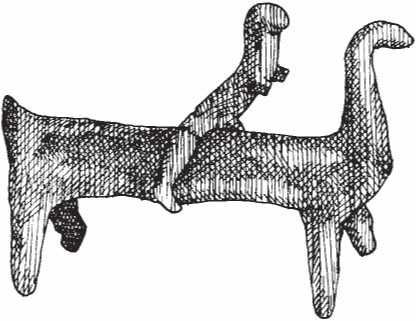

Figure 3.9 Clay figurine of horseman, sixth century BC, Speikern, Germany. Length of horse: 8.7cm. Paul Jenkins.

Bulls.99 Representations at Camonica Valley depict captured wild animals surrounded by packs of dogs. Here there is evidence that the Camunians trained their dogs to drive beasts into snares.100 Arrian discusses the use of horses and hounds in hunting:101 he alludes to the employment of both these creatures in wearing down prey until it was too tired to run further, when the hounds would flush small game out of cover. Arrian comments upon Gaulish dogs called vertragi, whose name, he says, derived from the Celtic word for 'speed'. He describes them as being muscular, with lean flanks, broad chests, long necks, big ears and long muzzles. Strabo102 remarks that horses and dogs each enjoyed privileged status among the Celts because of their usefulness in the hunt.

There is some archaeological evidence for the presence of large, perhaps specially bred hunting-dogs. Some of the Danebury dogs were sufficiently large and robust to have been used for hunting quite large prey. The dogs found in the subterranean shrine of second - or third-century AD date in Cambridge103 were probably hunting-dogs; they were sacrificed along with a horse and a bull. The later Romano-Celtic shrine at Lydney (Glos.) was dedicated to a British god Nodens: many images of dogs were found on the site (chapter 8) including a superb bronze deer-hound (figure 8.2).104 It is very likely that some dogs were specially bred and trained for their aggressive temperaments. The close association between horses and dogs is reflected in some Iron Age bone assemblages, where their remains are found together in what may be ritual deposits, perhaps associated with a hunting cult. This occurred at Danebury often enough to be statistically significant,105 as also in

Figure 3.10 Bronze brooch in the form of a bird of prey wearing a collar, fourth century BC, from a grave at the Durrnburg, Hallein, Austria. Length: 3.2cm.

Paul Jenkins.

Cemeteries in the Compiegne region of northern Gaul and elsewhere. A grave in the cemetery at Tartigny (Oise) may have been a hunter's tomb: here, remains of a dog, horse and hare were found, carefully selected for deposition in the grave. The dog was about a year old and, in a rather gruesome ritual act, it had been skinned and eviscerated. The horse was represented only symbolically, by the placing of its mandible in the tomb.106

Traps and snares

Traps, pits, snares and lassos were all employed in the hunt. Caesar, speaking of German hunting methods, alludes to the capture of the wild aurochs by digging pits into which the animals fell and were trapped.107 Martial refers to the use of boar-traps, which lessened the danger to hunters.108 Modest hunting, perhaps undertaken by peasants rather than the aristocracy, both for food and to protect the crops, seems to have been particularly dependent upon snares, lassos and traps.109 All these methods are depicted on the rock art of the Iron Age Camunians. Some scenes show aquatic or marsh-birds caught by snares and then dispatched with a spear or axe. The Camunians set snares for small animals, like fox and hare, and the dogs would often do the rest.110 The negative evidence of archaeology is reflected in the rock art, in that fishing is rarely depicted by the

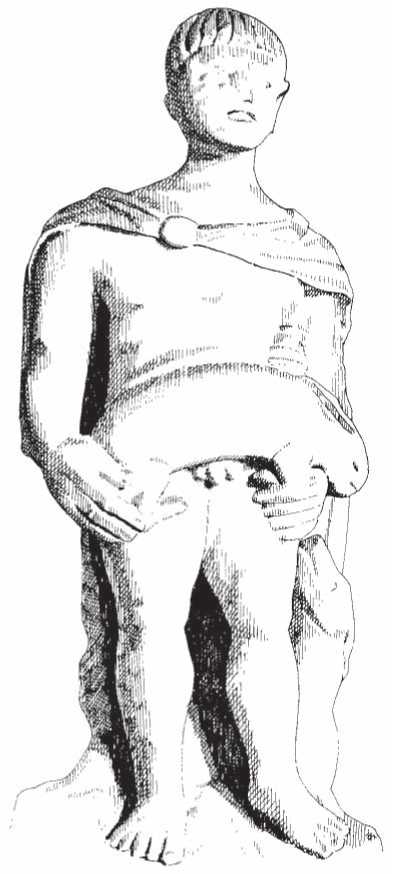

Figure 3.11 Stone statue of a hunter-god with knife, hound and hare, Romano-Celtic date, Touget, Gers, France. Height: 75cm. Paul Jenkins

Camunian communities. But there are a few carvings which record the catching of fish using harpoons or traps.111

World History

World History