From a global perspective, biological, archaeomet-ric, and genetic evidence together appear to support the ‘out-of-Africa’ model for the origin of anatomically modern human. This model suggests African-evolved modern humans arrived in East Asia and replaced Asian hominids around 40 thousand years ago. However, the last decade of investigations revealed New data from southern China that continues to encourage some scholars to advocate a model of independent modern human evolution in China, namely the ‘multiregional model.’ Clearly, no matter which origin theory one ascribes to, the Upper Pleistocene fossil remains recovered in China are of critical importance.

At present, there are up to nearly 40 archaeological sites in China where fossil remains of anatomically modern humans have been recovered, among which fossils from the Zhoukoudian Upper Cave, Ziyang, and Liujiang are the most important. Conventionally, modern humans from the Upper Cave at Zhoukoudian were once believed to be continuously evolved from the Zhoukoudian Locality 1 Homo erectus. Although this notion has been long discarded, some scholars still insist that Asian modern humans shared some biological features of their precedent Homo erectus, such as mandibular torus, shoveling upper incisors, and nasal breadth, which are usually considered to be part of the physical identity of today’s Asian Mongoloid race. Liujiang fossils present more features that can be related to Homo erectus, while fossils from both the Upper Cave and Ziyang are regarded as the best examples of Homo sapiens sapiens in China. The new discovery of modern human fossils including a lower jaw was made at Tianyuandong cave about 6 km southwest of the Zhoukoudian Locality 1, and the Uranium-series dating gave the age of cave deposit at 25 thousand years ago contemporary with that of the Upper Cave. However, the problem is that so far most of these fossils are incomplete causing difficulties in statistical comparisons. As almost all of these well-known fossils under study are younger than 50 thousand years ago, the lack of fossil samples dated to between 100-50 thousand years ago in China is a critical weakness in the indigenous development theory. In other words, current fossil data point to discontinuity of local human evolution (see Paleoanthropology).

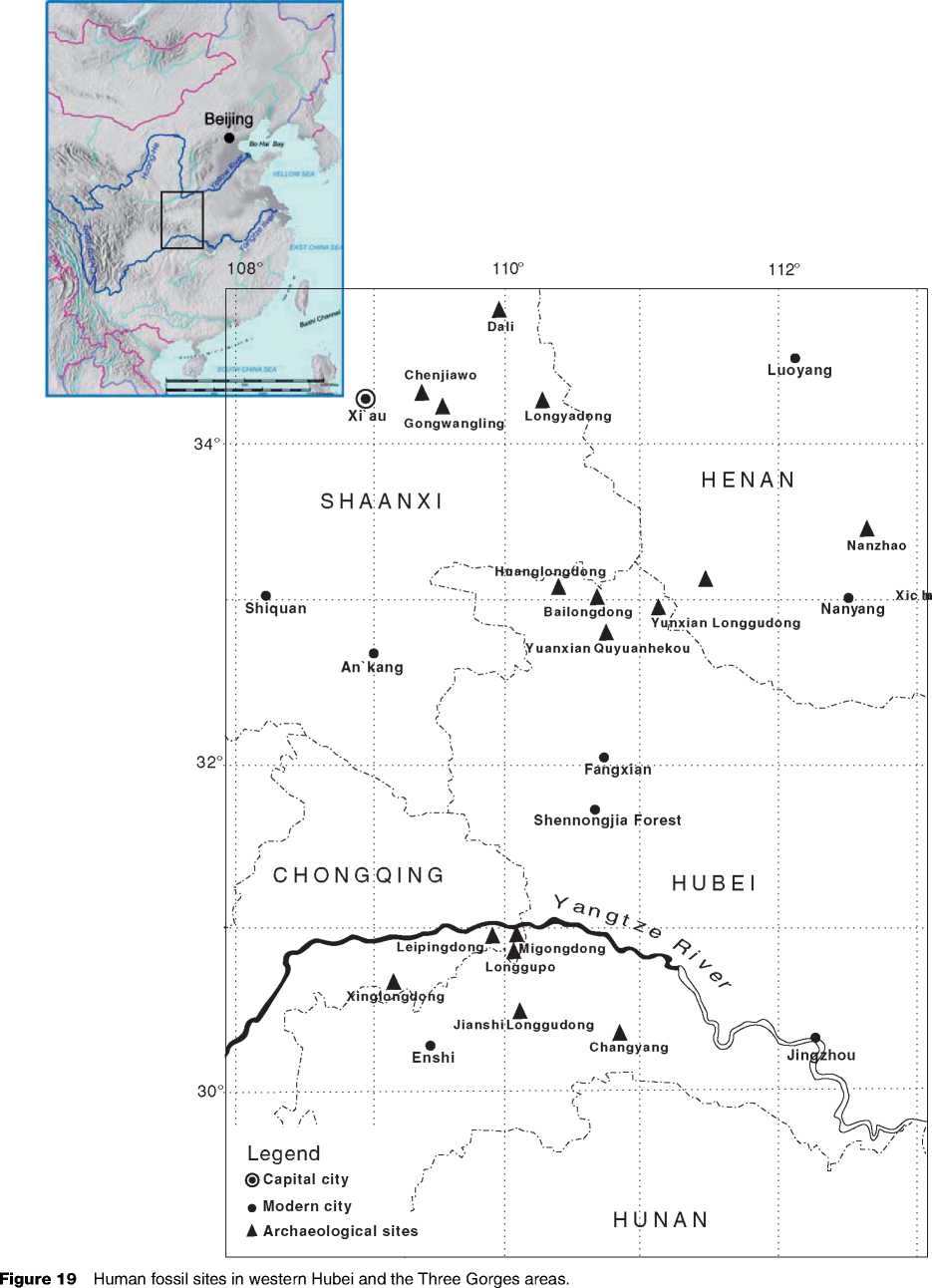

However, this situation may change in the near future. Over the past decade, full-scale field investigations and extensive fieldworks have been undertaken in the western Hubei province and in the Three Gorges area as part of cultural heritage management associated with the Three Gorges Dam Reservoir and the subsequent South-to-North Water Transfer Project. As a result, dozens of Pleistocene faunal locations as well as human cultural remains were identified. Today, central-western China, with 16 locations, has become the richest area for recovering hominid and modern human fossils in East Asia, most of which are in western Hubei (Figure 19). These fossils range from possible Lufengpithecus, to Homo erectus, Archaic Homo sapiens, to Homo sapiens sapiens.

What is more significant is that for the first time modern human fossils dating back to around 100 thousand years ago are being recovered from four newly identified sites.

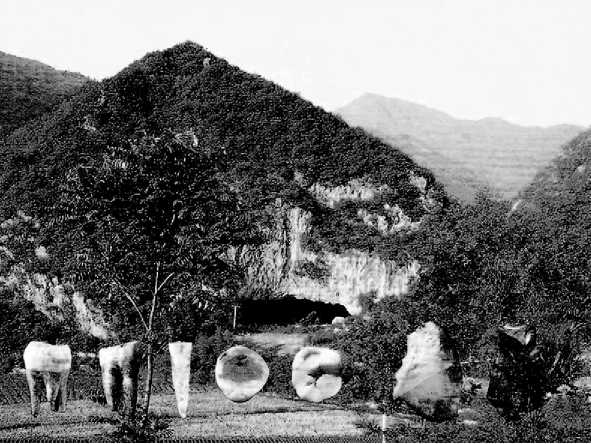

At present, Yunxian Huanglongdong site yielded the earliest examples of modern human fossils. The site is a limestone cave more than 100 m deep and 10 m tall (Figure 20), with Palaeolithic deposits more than 2 m. In 2004, five teeth (left second upper incisor, canine of upper jaw, third molar of upper jaw, right second molar of mandible, and left third molar of mandible) were recovered from Layers 4-6, in association with stone tools and faunal remains. The teeth belong to different individuals, all well preserved with clear features of the crown and root. The excavators believe that the morphological features of these teeth fall in between Archaic Homo sapiens and modern Chinese. The faunal assemblage features the South China giant Panda-Stegodon fauna indicative of the late Middle Pleistocene, in conjunction with a calibrated date of Uranium-series date that suggest the rather antique age as early as 94 thousand years ago or at least within the range of 103-44 thousand years ago in age based on uranium-series and ESR samples.

The Xinglongdong cave at the western end of the Three Gorges also yielded four modern human teeth embedded in Stegodon fossil deposits that point to geological dates of late Middle Pleistocene (c. 150120 thousand years ago). According to the excavators conducting the 2002-2004 fieldwork session, cultural remains at the site are rich and include rare stone animal figurines. These could be the earliest examples of Palaeolithic art in China. The other two new sites, Migongdong and Leipingdong, both in Wushan County, retain well-preserved late Middle Pleistocene (or early Upper Pleistocene) deposits in the caves where skull fragments as well as teeth were recovered. All of these fossil remains have yet to be studied as the ongoing research continues, but they will undoubtedly shed new light on the study of early modern human in China.

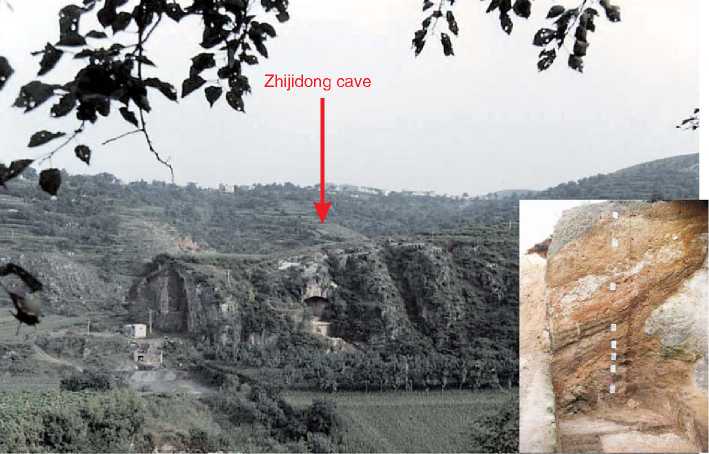

New archaeological findings near Zhengzhou city of Henan also seem to suggest cultural continuity in central China. Identified in the 1980s, Xingyang Zhijidong is a rock-shelter type cave with deposits more than 20 m deep and covering periods from Early Upper Pleistocene to Early Holocene (see Asia, East: Early Holocene Foragers). The site was excavated in the early 1990s, and then again in 2001-2004 by Peking University (Figure 21). A series of AMS 14C date and OSL dates taken from Layers 2-7 suggests an occupational age ranging from 50 to 35 thousand years ago, when the cold and dry climate during the Last Glacial Period took place. Cultural remains tends to be continuous in terms of technological development, although a trend of small flake tools in the later occupational time, possibly developed from pebble-core tools in early times, is observed from lithic assemblages. The archaeologists working on the materials suggest that such transitions could be adaptive to climate changes. Continuous occupations of the cave retain evidence of modern human behavioral such as hearths, activity floor, and procurement strategies. The raw materials used for stone tools are dominated by quartzes and chert that had to be transported from long-distance sources. Toolkits are represented by side-scrapers and burins, which are clearly the same

Figure 20 Images of the Huanglongdong cave site in western Hubei province and associated modern human teeth and stone tools.

Figure 21 The Zhijidong Cave near Zhengzhou City, and its deposit (insert).

Cultural manifestation as small flake tools of northern China in early periods.

Therefore, while there is not yet enough evidence to refute the ‘out-of-Africa’ theory for the origin of modern humans in East Asia, new data accumulated over the last decade, both biological and archaeological, suggest that the possibility of independent evolution cannot be ruled out. New findings from China will continue to stimulate what hopes to be a fruitful debate on the issue of human origin. Chinese archaeologists and anthropologists regard this evidence supportive of a new model, namely the ‘continuity with hybridization,’ originally proposed by palaeoan-thropologist Wu Xinzhi in the middle 1990s as a variation of the ‘multi-regional origin’ theory.

World History

World History