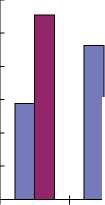

Only a proportion of diseases affects bone, often less than 5%, so the diseases that one studies in bones are only a fraction of those that affect the human body. When diseases do affect bone, they often do so in their latter stages when disease becomes chronic. Acute conditions, on the other hand, often cause death before the disease affects bone; these diseases cannot be studied by way of lesions in human remains, except in instances of unusual preservation of soft tissue and by palaeodemographic analysis. Skewed palaeo-demographic profiles toward a high frequency of juveniles and young adults may reveal the passage of a contagion, even in the absence of skeletal lesions (Figure 1).

Bone lesions associated with disease result from metabolic insult to bone remodeling. Healthy, normal bone possesses a fine balance between modeling (or growth) and remodeling (cellular turnover or development) that is mediated by osteoclasts, specialized bone cells that resorb (i. e., remove) bone, and osteoblasts, those cells that are responsible for laying down new bone. Because this balance - between removing old or damaged bone and replacing it with new bone - is disturbed by disease pathogens, bone response to disease tends to be very similar for a wide range of conditions. Inflammation of the periosteum, the neural and vascular supplying membrane around bone, is a common response to infection. Under conditions of

Comparison of the Royal Mint and Beckett Street AD 1849 mortality profiles

Age range

Figure 1 Plague, as identified at the Royal Mint Site, London, UK (blue), strikes indiscriminately, affecting young adults disproportionately, more often those living in urban centers in the past, where contagions spread more readily. In contrast, the mortality profile of a cholera cemetery (red) based on archive documents from mid-nineteenth-century Beckett Street, Leeds, UK, demonstrates that this water-borne infectious disease disproportionately affects the very young and the very old. Both are acute diseases that leave no bone lesions. From Margerison, BJ (1997) A Comparison of the Palaeodemography of Catastrophic and Attritionai Cemeteries. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Bradford.

Active hyperemia (decreased arterial blood flow with high oxygen tension), bone is resorbed, while passive hyperemia (increased venous blood flow under moderate oxygen tension) produces bone formation. Thus, some diseases result in bone loss, others in increased bone deposition, and still others demonstrate a mixed response of bone deposition and bone resorption. Although bone response is not specific to particular disease pathogens, the patterning of lesions in the skeleton often is. Not only the type of bone response but also the patterning of lesions is thus fundamentally important to differentiating among diseases.

World History

World History