This summary has highlighted current research issues and directions in landscape archaeology within the last decade. Instead of the traditional rationalization of archaeology and antiquity - war, population increases, trade, religion, irrigation agriculture - most without evidence to support them, the advent of high-resolution palaeoenvironmental chronologies of climate change have spawned a new generation of models which tie sequences of culture change to detailed records of climate change. Recent archaeological and ecological studies have also stressed the magnitude of human and cultural impacts to the environment in prehistoric and early historic times.

These multiple lines of new evidence and explanations indicate that (1) archaeology must address ‘culture change’ with the assumption that ‘environmental change’ has been ongoing over the last 3000 years, (2) these changes have not been uniform, but have shown major fluctuations in the Holocene, (3) that these Holocene fluctuations in climate and sea-level rise are in addition to any modern ‘Green House’-ascribed postindustrial climate shifts, (4) fluctuations in the rate of sea-level rise suggest that now inundated coastal bays, estuaries, and drainages, may have been more exposed and more available to human occupation that previously assumed, (5) palaeoenvironmental reconstructions will have to address ancient landscapes from the perspective of what they looked like in the ‘past’, versus the present, and finally (6) archaeological evidence may represent an important source of data to fill existing Late Holocene gaps in record of sea level rise and environmental change.

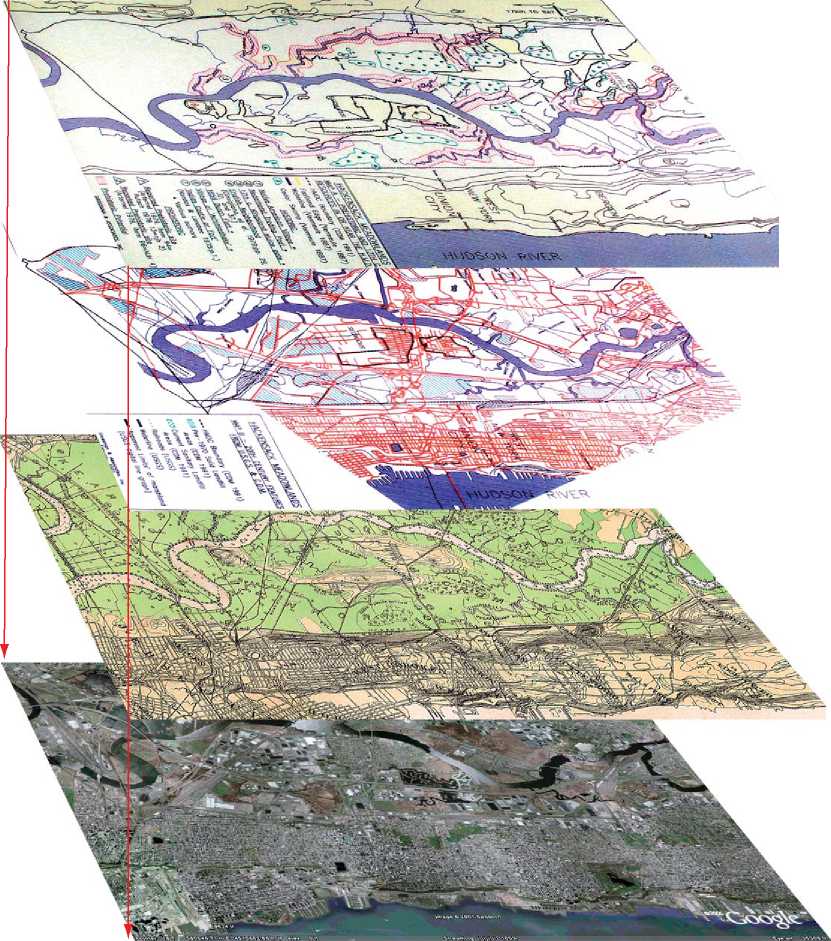

Over the last 10 years, most of the major new insights have derived from refinements in the resolution and dating of regional sequences. Recent breakthroughs are beginning to highlight the ‘interplay’ between sequences ‘of environmental change, sea level rise, and ancient topography’. Instead of only ‘diachronic’ or chronological treatments - as in ‘point samples of ‘straws’ punched through a prehistoric layer cake’ - we will have to use the modern geospatial tools of GIS, 3D terrain modeling, and palaeoecolo-gical reconstruction to ‘geospatially correlate’ these

Potential

Archaeological survivals

Subtraction of all modern infrastructure and impacts

Scaled GIS overlay of historic maps

Digital air photo project base map

Figure 5 Historic Impact Analysis using GIS to define un-impacted areas that could contain potentially surviving prehistoric and historic cultural resources after “subtracting” modern impacts from modern construction and landfills within the New Jersey Hackensack Meadowlands. (By Joel W Grossman Ph. D., © Joel W Grossman Ph. D. 2008. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.)

High-resolution chronologies of environmental change, with the subtle topographic variables and contexts of past archaeological landscapes, some exposed, some buried, and some submerged (Figure 3). From a treatment of archaeological landscapes as 2D and predominantly static, we must now see them as 3D, geospatial and dynamic.

See also: Archaeometry; Carbon-14 Dating; Chemical Analysis Techniques; Civilization and Urbanism, Rise of; Cultural Ecology; Cultural Resource Management;

Dendrochronology; Ecofacts, Overview; Electron Spin Resonance Dating; Geoarchaeology; Landscape Archaeology; Luminescence Dating; Maritime Archaeology; Neutron Activation Analysis; Obsidian Hydration Dating; Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction, Methods; Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction in the Lowland Neotropics; Paleodemography; Pa-leoethnobotany; Pedestrian Survey Techniques; Pollen Analysis; Remote Sensing Approaches: Aerial; Geophysical; Settlement Pattern Analysis; Settlement System Analysis; Spatial Analysis Within Households and Sites; Toxic and Hazardous Environments.

World History

World History