The pre-eminence of the Franco-Cantabrian cave art has in some respects overshadowed the appreciation of the many other rock art traditions of Europe. In France, for instance, the extensive corpus of Fontainebleau receives scant attention, simply because it is of the Holocene rather than the Late Pleistocene. Much the same can be said about Spanish traditions,

Figure 4 Part of the southern wall of the quartzite cave Daraki-Chattan, India, bearing some of the oldest known rock art of the world. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Figure 5 Petroglyphs believed to depict skiers, Zalavruga site complex, northern Karelia, Russia. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

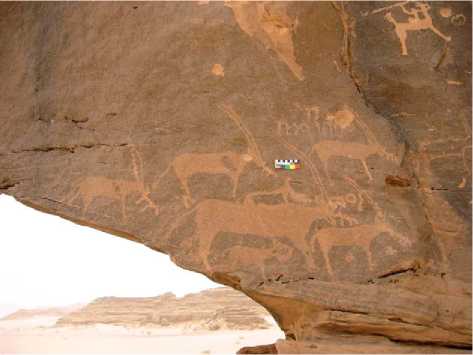

Figure 6 Petroglyphs at Ain Jamal, Jabal Qara, southern Saudi Arabia. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

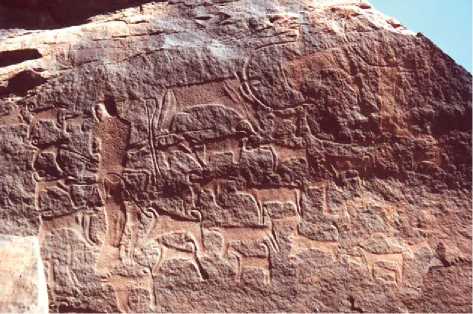

Figure 7 Neolithic petroglyphs at Shuwaymas site complex, northern Saudi Arabia. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

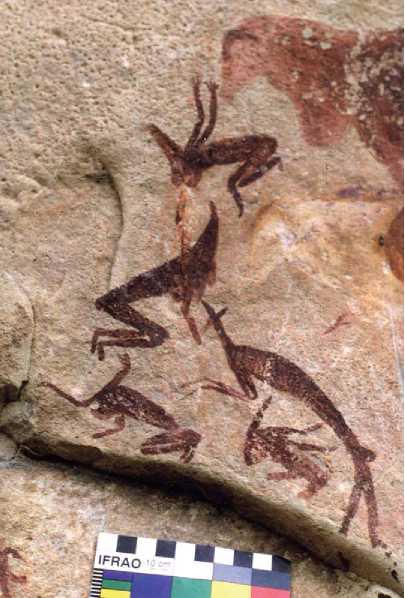

Figure 9 Bushman/San paintings near Bethlehem, South Africa. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Province, China. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Region, Western Australia. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

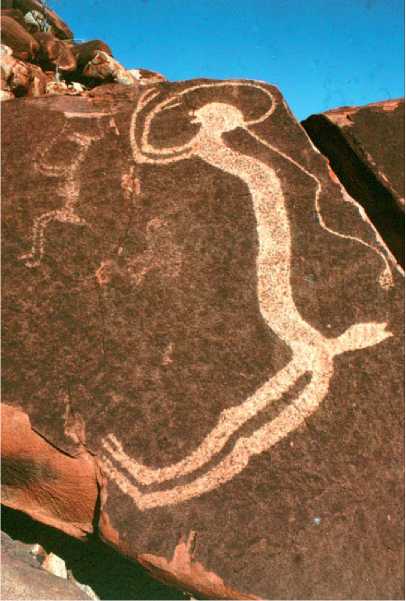

Figure 8 Petroglyph of ornate zoomorph, Helan Shan, Ningxia Figure 10 Petroglyph of a malevolent spirit being, Woodstock

Figure 11 Paintings of initiates at Garnawala, Wardaman tradition, Northern Territory, Australia. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

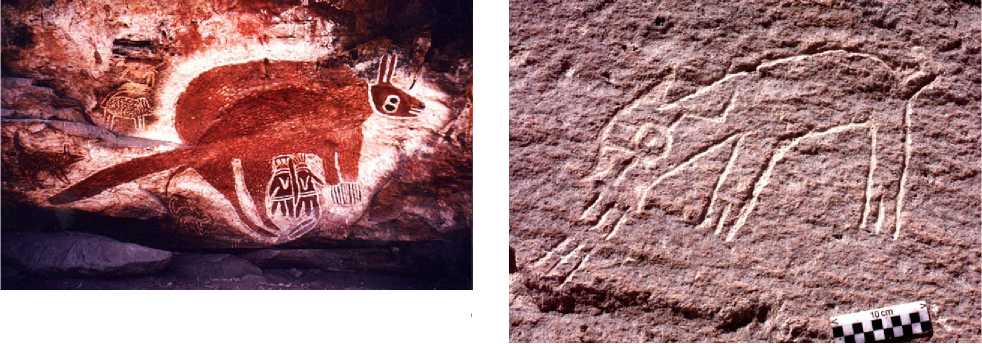

Figure 12 Macropod and other beings, Victoria River District, Northern Territory. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Figure 14 Petroglyph of a quadruped, which seems to resemble a ‘barking dog’, southern Peru. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Figure 13 Recent pictograms at Nourlangie, Arnhem Land, Australia, painted by Nayambolmi in 1964. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Such as the Galician petroglyphs or the Levantine paintings. Alpine petroglyphs have fared somewhat better, especially in the western Alps at Mont Btigo and southern Alps in the Tellina and Camonica valleys. There are scattered sites or smaller concentrations in nearly all European countries, but the only other major series of sites extends across Scandinavia, from Denmark to Karelia. It comprises mostly petroglyphs, but pictograms do occur, especially in Finland. Little is known about the rock art of the Balkans and Greece, but there appears to be a fair amount of it. Portugal, Britain, and Ireland are well endowed with petroglyphs, typically nonfigurative. Most of European rock art has been attributed to the Metal Ages, some may be older, and traditions that are more recent certainly exist. It needs to be cautioned that credible dating is rarely available, and revisions still have to be anticipated. For instance, the Scandinavian

Figure 15 Typical style of the petroglyph complex Toro Muerto, Peru, with animated anthropomorphs and copulating zoomorphs below. Photograph by R. G. Bednarik.

Petroglyphs are mostly attributed to the Bronze and Iron Ages, but it is possible that more recent people, such as the Vikings or the Saami, were involved in their making.

Asia, of which Europe is only a small appendage, comprises several large bodies of rock art that surpass numerically any European regional corpus. Most of the countries of the Middle East are rock art rich, especially Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Israel. Here, early inscriptions often occur alongside petroglyphs, helping to unravel the chronology, and suggesting that much of the art dates from between 3000 and 1400 BP. With the advent of Islam, rock art production was severely reduced although practices did continue. The rock art of the Caucasus region has only begun to attract interest recently, and very little is known about Turkish or Yemeni rock art. Researchers have noted the occurrence of concentrations in Pakistan, but so far no research of substance has been conducted there, while in the several countries to the north, it has only begun in the most recent years. Across Central Asia, including the Tibetan Plateau, there are numerous reports of rock art, but a great deal has been destroyed by Moslems, for instance along the Silk Road. Much better explored is the rock art of Siberia, of which concentrations appear along the Yenisey (impact petroglyphs) and Lena rivers (abrasion petro-glyphs and few paintings). In Mongolia, the greatest assemblages are found in the Altai Mountains. The impressive iconography of the Central Asian regions, sometimes dominated by apparently human faces described as ‘masks’, or by extraordinarily ornate ‘deer stones’, continues into China, especially in the Ningxia Province and Inner Mongolia. Among the more than 10 000 Chinese sites, those in the north are almost entirely of impact petroglyphs, while the situation is reversed in southern China. Nearly all rock art there is of pictograms, especially in the rock art-rich Yunnan Province, or in Guangxi Zhuangzu with its incredible site at Huashan, where monumental paintings extend to 40 m height.

Japanese rock art is mainly found in small occurrences on boulders and stelae, but information is often unreliable. The countries of Southeast Asia all feature rock art, but publications are very sparse and no researchers have worked in most areas. A notable exception is Borneo, with its numerous limestone cave art sites of paintings and stencils. In the Philippines, sound ethnographic observations concerning cave paintings are available from Palawan. India offers one of the largest and best-explored rock art bodies in Asia, with paintings dominating in all provinces except in the far north and northwest, in the Deccan and the extreme south. The richest repositories are found in the rock shelters of the central regions, particularly in Madhya Pradesh. They include the best-known Indian site complex, Bhimbetka, of about 500 painted shelters (see Asia, South: Paleolithic Cultures).

Africa, too, boasts some massive rock art concentrations. These begin with the several art regions of the Sahara, extending from Morocco to Egypt. The arid conditions have greatly facilitated the preservation of rock art of the last six milleniums. In terms of its artistic finery, Saharan art is matched by few traditions, one of them being the Bushmen/San rock paintings of southern Africa. Other painting and petroglyph traditions occur also in that region, and the Pleistocene finds of portable paintings in Apollo 11 Cave, Namibia, imply that very early traditions once existed. Other portable art from Africa is even older, but no African rock art has been convincingly demonstrated to be of the Ice Age. There are extensive corpora of rock art in Tanzania, Kenya, Gabon, Sudan, and smaller occurrences in probably all remaining African countries, but as in Asia, there are also great gaps in our knowledge of distribution.

The situation is considerably better in Australia, where all major rock art regions have been identified and the issue of antiquity is somewhat clearer. The major bodies in the rock art-richest country are the petroglyphs of the Pilbara, the paintings of the Kimberley and Arnhem Land, and the mixed rock art of the Victoria River District and Cape York Peninsula. Other notable complexes are the stencil-dominated sites of central Queensland, especially in Carnarvon Gorge, the Sydney sandstone petroglyphs, and those of the Olary district in South Australia. In general, the number of sites increases from south to north, with the limestone cave art along the southern coast and in Tasmania forming an unusual feature. A remarkably large part of Australian petroglyphs seems to be of the Pleistocene, having been estimated to be as great as 20% of a corpus thought to be well in excess of 100 000 sites overall. Many of the islands of Oceania are also well endowed with rock art, among them New Guinea, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Canada’s rock art is comparatively sparse, with minor concentrations in British Columbia and relatively isolated finds in most other states. The United States, by contrast, has major occurrences, especially in the southwestern states. The Chumash paintings and Coso Range petroglyphs in California, the numerous sites across Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico all form a massive body composed of many traditions. Most other states also contain rock art where suitable conditions pertain. In terms of antiquity, North American rock art seems to be consistent with most of the rest of the world: all or nearly all the rock art is of the Holocene. The western art province continues in the neighboring Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, with notably impressive painting sites in Baja California. Smaller concentrations occur in much of Central America, and there is hardly a major island in the Caribbean that lacks rock art. In both regions, paintings as well as petroglyphs occur.

All countries of South America feature rock art sites, but the major corpora are found in the Andean region, from western Venezuela to Patagonia. The largest single site is perhaps Toro Muerto in southern Peru, consisting of several square kilometers of pet-roglyphs. Other notable occurrences in Colombia, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina have been subjected to detailed study, as have the extensive traditions of northeastern Brazil.

World History

World History