Phoenician Homeland

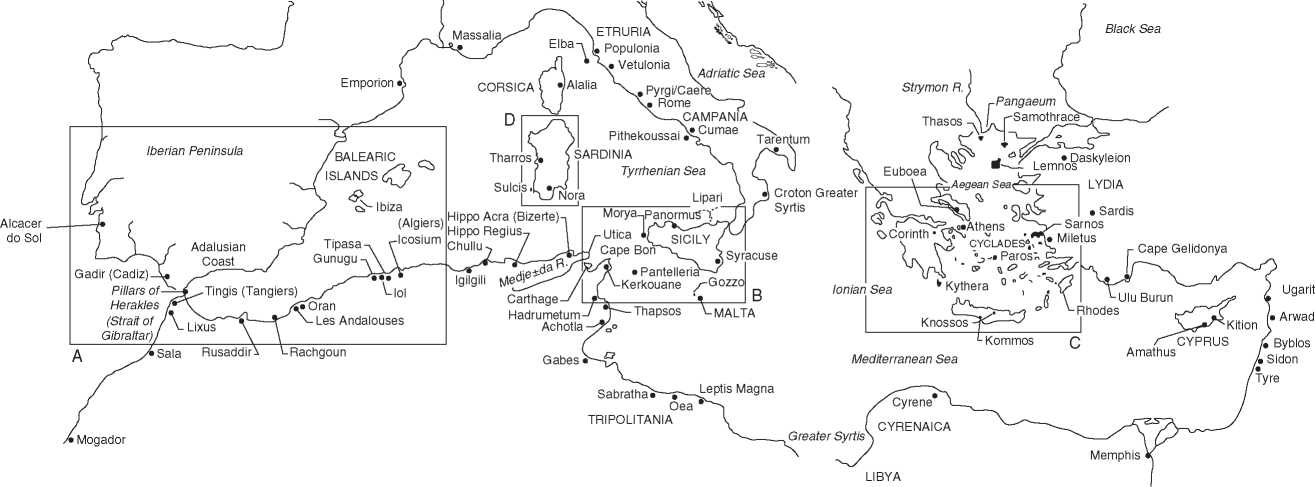

The following is a summary of the major Phoenician coastal ports (see Figure 1).

Tyre The peninsular setting of modern Tyre (Pun. Sor (‘rock’)) today differs greatly from that of the ancient city. The headland upon which it stands is the result of successive sediments deposited on a mole built in 332 BC by Alexander the Great. In antiquity, Tyre was an island emporion, situated originally on two adjacent offshore reefs. Traces of bedrock on Tyre’s western edge and in the adjacent sea bed reveal that the principal island upon which Tyre was founded was a long narrow reef some 500 m in extent.

Owing to the dense overlay of later construction, excavations in the heart of Tyre have not been possible. Stratigraphic information to date has been ascertained only by a deep sounding undertaken in 1974, which revealed that Tyre was originally occupied in the Early Bronze Age, corroborating an ancient Tyrian tradition, reported by the Greek historian Herodotus, that the city was founded 2300 years before his day (around 2750 BC: Hdt. 2.44). Following a long hiatus in occupation encompassing the Middle Bronze Age, the city was resettled at the start of the Late Bronze Age. Judging from the archaeological record, permanent habitation on the island does not seem to have taken root until the late fifteenth century BC, with comprehensive urban development following in the mid-fourteenth century. The archaeological and written record are in unanimity about the urban character of Iron Age Tyre: the city was densely populated, perhaps far more so than any of its Phoenician mainland counterparts with the possible exception of Arwad. The 1974 sounding, in fact, yielded nine distinct Iron Age building levels that bear witness to continuous efforts at remodeling and terracing. From this time forward, the pier-and-rubble technique, a Phoenician trademark, was widely utilized; large-scale buildings were marked by handsomely dressed walls of marginally drafted ashlar masonry (see Tab le 1 For the definitions of time phases referred to in this article).

Tyre’s two harbors, situated to the north and south of the emporion, were noted by a variety of classical authors, including Pliny (N. H. 5.76), who observes that they were connected by a canal which traversed the city. Its northern port (known in antiquity as the ‘Sidonian’) was a natural bay, sheltered from prevailing winds by the island itself and by a strip of offshore reefs that protected its entrance; it functioned as a closed harbor situated within the city walls. Tyre’s southern port, the ‘Egyptian’, was a built harbor protected by two great offshore breakwaters.

Excavations undertaken at Tyre from 1997 to 1999 have uncovered a small portion of the city’s main adult cemetery, a cremation necropolis at Al-Bass on the opposing mainland. Consisting of burials in urns set within shallow, excavated pit graves along a sandy shoreline, the cemetery’s vast extent (estimated at 40 000 m2) and its prolonged use (spanning some 400 years, from c. 1000 to 600 BC) underscore the spread and longevity of the cremation practice within the funerary life of the city.

Sarepta The coastal town of ancient Sarepta (modern Sarafand) occupies a low mound situated on the promontory of Ras el-Qantara, overlooking a broad bay with sheltered anchorage. Explored by the University of Pennsylvania from 1969 to 1974, Sarepta represents the first in-depth excavation of an Iron Age

Figure 1 Map of Mediterranean with Phoenician sites. Based on Markoe G (2002) Peoples ofthe Past. Phoenicians. London: British Museum Press.

Chalcolithic 4500(?)-3100BC Early Bronze Age 3100-2000 BC Middle Bronze Age 2000-1550 BC Late Bronze Age I 1550-1400 BC Late Bronze Age II 1400-1200/1150BC Iron Age I 1200/1150-1000BC Iron Age II 1000-586BC Iron Age III (Neo-Babylonian) 586-538 BC Persian period 538-332 BC Hellenistic period 332-64/63 BC

Mainland Phoenician settlement. Soundings made in two areas on the tell (X and Y) have revealed a continuous sequence of habitation extending from the beginning of the Late Bronze Age - the date of the city’s foundation - through the Hellenistic period. Sounding Y, made on the highest part of the mound, yielded an uninterrupted sequence of 11 occupation strata marked by complexes of courtyard houses equipped with potters’ kilns and bread ovens. Sounding X revealed an extensive industrial quarter located near the harbor at the northern periphery of the settlement. Much of this district was devoted to pottery production; findings included the remains of 22 stone-built firing kilns in addition to slip basins and tanks for washing and storing clay. This sounding also produced an eighth century stone ashlar shrine to the goddess Tanit-Ashtarte equipped with benches, an offering table, and a central cultic pillar.

The ancient settlement was flanked to the north and south by two small harbors; excavation of the southwestern port at Ras esh-Shiq uncovered a stone-built quay erected in the first century AD. No evidence has yet been found for the usage of either harbor facility prior to the Roman period.

Sidon The port city of Sidon (Pun. Sdn) is situated on a rocky promontory bordered by a line of coastal reefs. The settlement, marked by an oval mound of roughly 145 ac, lies adjacent to two natural harbors: a southern circular cove and an enclosed northern port. As at Tyre, the density of modern settlement at Sidon has inhibited archaeological exploration. Concerted excavations, however, have been undertaken in recent years by the British Museum under the auspices of the Lebanese Department of Antiquities. Centered in the area immediately north and east of the medieval St. Louis Castle, this work, begun in 1998, has succeeded in documenting a continuous stratigraphic sequence extending from the beginning of the Early Bronze Age through the Iron Age.

To the south of the city acropolis, along the shore of the southern circular cove, stands a 40-m-high accumulation oF discarded murex shells marking the ancient emplacement of a large purple dye installation. As Poidebard’s early investigations have shown, Sidon’s chief port facility was situated immediately north of the city. This natural harbor, which was sheltered from the prevailing winds by a rocky offshore island and a northeasterly chain of reefs, constituted the city’s ‘closed port’ - first mentioned by Pseudo-Skylax in the mid-fourth century BC.

Archaeological research over the last century has provided substantial data on the distribution of Sidon’s suburban cemeteries. Special attention may be drawn to the necropolis of Dakerman, a vast coastal cemetery located immediately south of the city. Excavations undertaken there by the Lebanese Department of Antiquities have yielded several hundred tombs of various types ranging from the fourteenth century BC through the early Roman period. Sidon’s royal necropolises of the Persian and Hellenistic periods (Mogheret Ablun and Aya) have been located along a line of hills extending east and southeast of the city.

The most important of Sidon’s suburban sanctuaries was the precinct of Eshmun, located to the north of the city on the southern slopes of the Nahr el-Awali valley. Erected over a series of split-level terraces, this temple complex, founded in the sixth century BC, was the focus of excavations undertaken by the French from 1963 to 1978.

Beirut The ancient port of Beirut (Pun. B’rt) is situated on a rocky promontory with a sheltered harbor. Known previously from scattered textual references, the ancient city has now been revealed, thanks to archaeological research undertaken in connection with the redevelopment of war-devastated downtown Beirut. Such excavations, begun in 1993 under the auspices of the Lebanese Department of Antiquities, have unearthed numerous sectors of the pre-Roman city, including Beirut’s settlement mound and an adjacent residential precinct dating to the Persian period.

The original settlement occupied an elliptical tell, situated on a small limestone-eroded outcrop, roughly 5 ac in extent. Its core, site of the ancient acropolis, was completely demolished during construction of the medieval Crusader castle, whose foundations reached bedrock. Recent excavations around the Crusader structure have uncovered evidence for an occupational sequence dating back beyond the Middle Bronze Age, when the site was first fortified and equipped with a monumental gate. The mound itself underwent six defensive phases lasting until the Persian period, when settlement spread well beyond the confines of the tell. To the west, in the area of the modern souk, or market place, excavations have uncovered the remains of a residential district with well-preserved dwellings of pier-and-rubble construction laid out in an orthogonal plan. In the area immediately adjacent to the northwest, a large quantity of murex shells and a basin complex were uncovered, attesting to local purple dye production. As excavations have revealed, Beirut underwent extensive urban development beginning in the Hellenistic period, when the ancient city achieved its historic form.

Byblos The seaport of Byblos (Pun. Gbl) is situated on a promontory with two small adjacent harbors, its principal settlement situated on an elevated, circular tract of land approximately 7 ac in size. A planned city with a massive stone rampart and two gates, the Early Bronze Age city was an important coastal emporion. As recent studies have shown, its urban development was centered on a rock-cut well or spring situated in a central depression on the promontory. Beginning in the third millennium BC, the northern sector of the mound was converted into a sacred precinct by the erection of two monumental sanctuaries: a temple to Baalat Gubal (Lady of Byblos) and an L-shaped temple dedicated to an unidentified male deity. The latter structure was subsequently dismantled and its foundations re-employed in the construction of a sanctuary (known as the Obelisk Temple) dedicated to the god Reseph. The Baalat Gubal and Obelisk sanctuaries were maintained with modifications down through the Hellenistic period. Earlier excavations undertaken by the French in the southern sector of the promontory have uncovered the remains of a residential district dating to the Middle Bronze Age. Composed of roughly 100 two - to four-room house units densely arranged in four blocks, this area may have housed personnel attached to the sanctuary.

The urban extent of Iron Age Byblos remains a complete unknown, although scattered clues point to the city’s development in the plains east of the acropolis. Building activity probably reached a peak in the Persian period, when the city prospered economically as a regional administrative and defensive center under the Achaemenids. It was at this time that a monumental platform and stone-pillared building (marking a Persian governor’s reception hall) was erected in the northeast sector of the city walls.

As for the city’s harbor facilities, the twin bays located north of the acropolis are both extremely small and thus unsuitable for large ships. As has been recently proposed, the city’s primary needs may have been served by the larger bay and riverine estuary that stood south of the acropolis. If this reconstruction is correct, Byblos’ topography would conform with that of a typical Phoenician port, situated on a headland flanked to the north and south by separate harbors.

Arwad Ancient Arwad (Pun. ’rwd (‘refuge’)) occupies a roughly oval-shaped island of approximately 100 ac situated roughly 2.5 km off the Syrian coast opposite mainland Antaradus (modern Tortose). The urban history of this Phoenician island emporion, which remains completely unexcavated, is virtually unknown. Although Arwad was occupied continuously from at least the third millennium BC, its earliest surviving architectural vestiges (i. e., the monumental city ramparts) date only from the Roman period. Ideally situated for trade, Arwad possessed a twin harbor facing east toward the mainland; its northern and southern bays were separated by a natural jetty some 60 m in length, which was augmented in antiquity by ashlar stone construction. As its massive Roman fortifications suggest, the Phoenician Iron Age city must have been protected by a fortified defensive wall that ringed the island. As the classical sources reveal, Arwad was densely populated; its city center, like that of Tyre, marked by multistoried houses (Strabo XVI.2.13). The high ground presently occupied by the medieval fortifications undoubtedly marks the ancient city’s acropolis and the site of its main sanctuaries. As at Tyre, the city’s main necropolises were probably located on the mainland opposite - in the region of Tortose, in whose vicinity a Persian-period cemetery of royal character has recently been discovered. As chance finds from the modern city suggest, a small cremation cemetery may also have been located in the island’s southern periphery. Like Tyre, Arwad was heavily dependent upon the mainland for its raw materials and agricultural staples. In addition to Tortose, Arwad’s mainland dependencies included coastal Marathus (Amrit), Arwad’s chief continental port.

World History

World History