The earliest good evidence for full mixed cereal and livestock farming is dated to between AD 400 and 600. Livestock associated with pottery known as Bambata, however, predates unequivocal agropastoralism by 200-300 years and is known from Southwestern Zimbabwe, Botswana, and northern South Africa. This Bambata Pottery is enigmatic and some suggest that it is the start of the Early Farmer sequence while others link it to pioneer pastoralists or hunter-gatherers. It may be part of a general process that resulted in the appearance of early sheep and pottery in the Cape.

Whatever the case, food production did not evolve from the local Later Stone Age. A ‘package’ comprising village life, cattle, sheep, and goats, domesticated crops such as sorghum and millet, pottery, and iron and copper metallurgy was introduced from north of the Limpopo River. This is evident because the ceramics are the southernmost expression of a much wider Early Farmer ceramic style found in central and East Africa called the Chifumbaze Complex. The Chifumbaze Complex is the archaeological expression for the complex southward movement of speakers of Bantu languages.

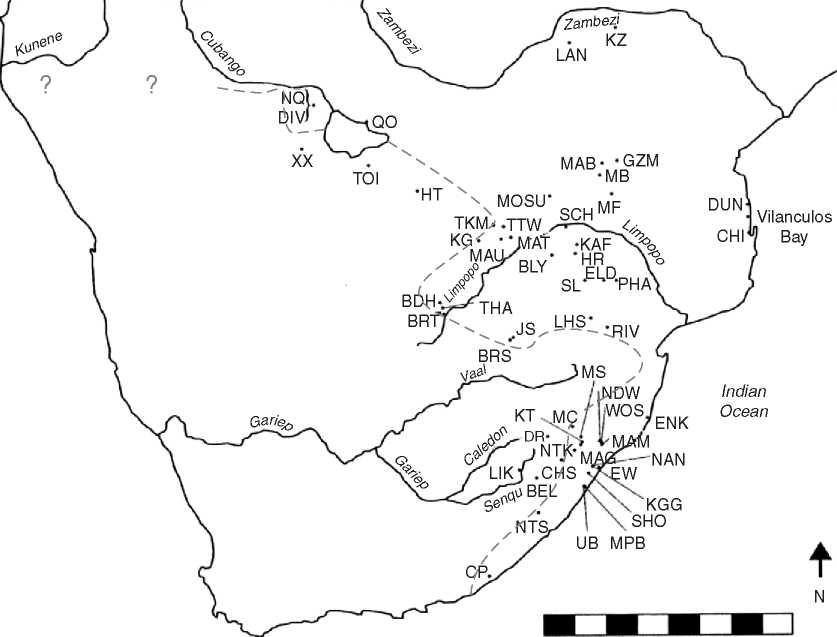

Early farmer settlements are only found in the northern and eastern areas of the country (Figure 1). This distribution falls within the summer rainfall region and reflects the rainfall and temperature tolerances of the primary cereal crops, sorghum, and millet. Farmers sought warm, lower altitude tree, and grassland habitats and built their homesteads next to rivers on deep alluvial soils. Where preservation allows, villages comprised a central cattle enclosure associated with metal working and ash dumps surrounded by a domestic, ring of huts and granaries. This was surrounded by a domestic ring of huts and granaries. There has been much debate as to whether this settlement layout can be interpreted through an ethnographic model called the Central Cattle Pattern, derived from late ninteenth - and twentieth-century Nguni-speaking ethnography. Huffman argues that cattle were probably socially and politically a key resource, particularly as a medium for bridewealth, from the inception of the early first millennium AD mixed farming ‘package’. Others have suggested that cattle only developed social importance toward the end of the first millennium.

Hunter-gatherers were drawn toward settlements and entered into exchange and barter relationships with Early Farmers. Most farmers were selfsufficient in terms of basic livestock, cereal, ceramic, and metal production, but some settlements were larger and others had dumps associated with central cattle enclosures and which contained the debris of prestige craft work and fragments of ceramic helmet

Atlantic

Ocean

0

200 400 600 800 km

Figure 1 Distribution of Early Farmers. Taken from Mitchell P (2002) The Archaeology of Southern Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Masks. The ethnographic model infers that these central zones were male activity areas and suggest shallow political hierarchies in which some production and ritual were centralized.

World History

World History