TEL, TELL

Atlal 4 [1980]: 69-106)5 may represent successive additions to the settlement. At various localities within tlie enclosed area, ruined buildings are visible. The Deparnnent of Antiquities has partially excavated three groups of these, the most important so far being tliat known as Qasr al-Hamra, where a complex of rooms, perhaps a palace, has been revealed. One of the rooms, clearly a shrine, contained stone offering tables, a cuboid stone carved with religious motifs, and an Aramaic stela similar to the Tayma’ stone. Altliough originally attributed to the Neo-Babylonian period, it now seems more likely tliat the shrine dates to Achaemenid times. The dating of otlier structures, including a number of burial mounds of various types, remains uncertain, aldrough pottery of the Nabatean and medieval periods has been found in various parts of the site.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abu-Duruk, Hamid Ibrahim. Introduction to the Archaeology of Tayma’.

Riyadh, 1986. Account of the recent Saudi excavations.

Bawden, Gaitli, and Christopher Edens. “Tayma’ Painted Ware and the Hejaz Iron Age Ceramic Tradition.” Levant 20 (1988): 197-213. Presents tlie case for the continuous occupation of Tayma’ throughout tlie first millennium BCE.

Edens, Christopher, and Gartli Bawden. “History of Tayma’ and He-jazi Trade during the First Millennium H. C.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 32 (1989): 48-103. Useful, comprehensive account, somewhat marred by an overly theoretical approach and an uncritical interpretation of the archaeological data. Lambert, W. G. “Nabonidus in Arabia.” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 5 (1972): 53-64. Masterly summary of the evidence which, however, pays too little attention to economic motives.

Parr, Peter J. “Pottery of the Late Second Millennium B. C. from North West Arabia and Its Historical Implications.” In Araby the Blest: Studies in Arabian Archaeology, edited by Daniel T. Potts, pp. 72-89. Copenhagen, 1988. This and the article below provide a critical reappraisal of the recent work at Tayma’.

Parr, Peter J. “Aspects of the Archaeology of North-West Arabia in the First Millennium BC.” In L’Arabie preislamique el son environnement historique et culturel: Actes du Collogue de Strasbourg, edited by Toufic Fahd, pp. 39-66. Leiden, 1989.

Peter J. Parr

For toponyms beginning with these elements, see under latter part of name. For a general description of tells, see Tell.

TELEILAT EL-GHASSUL, site located at the southern end of tlie Jordan Valley, approximately 6 km (4 mi.) east of the Jordan River and 5 km (3 mi.) from the nortlieast corner of the Dead Sea (3i°48' N, 35°36' E). It lies 290-300 m below sea levels its climate today is hot and dry, although water is available locally, about 40 m below ground level, and from the irrigation system of Jordan’s East Ghor Canal. When the site was founded, the area was swampy and settlement was made on a sand bank in the midst of slow-moving fresh water. It was surrounded by a rich growth of reeds, mosses, alder, and sedge.

Excavations and a series of radiocarbon dates give evidence of a thriving Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic agricultural community on the site for approximately one tliousand years (between 4500 and 3500 bge). The settlement was a large one, and at its most extensive occupation, in the Chalcolithic period, probably covered 20-25 hectares (49-62 acres; Hennessy, 1989). Its location was advantageous, at the junction of major north-south and east-west routes.

The site’s importance was first recognized by Alexis Mal-lon in 1929. Since then, the settlement has been the subject of a number of large-scale excavations by the Pontifical Biblical Institute (FBI) of Rome: from 1929 to 1938 under tlie direction of Mallon and Robert Koeppel, and in i960 under tlte direction of Robert Nortli. The site was more recently excavated by J. Basil Hennessy for the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem (1967) and the University of Sydney (1975-1978). [See the biography of Mallon.]

Ghassul has given its name to the Chalcolithic period in Israel and Jordan. However, since the original discussions about periodization at the site by William Foxwell Albright and Mallon in the 1930s, it has become increasingly evident that a considerable span of the site’s history more properly belongs to the classification Late Neolithic or Early Chalcolithic. In addition, the Ghassulian Chalcolithic should be confined to the site’s upper levels, which are but one regional variant of a series of widespread, related Chalcolithic communities.

The initial Late Neolltltic settlement was made up of large, circular, half-sunk houses and pit dwellings. All succeeding occupations were in large rectangular mud-brick buildings often constructed on a foundation of large river stones. Most houses consisted of a single long room (up to 12 X 3.50-5 m) with an occasional internal subdivision. The single doorway was in tlte long wall. Floors were of beaten eartli, but sometimes the pebble foundations were covered witli mud and lime plaster to give a more even surface. Walls were often finished witlt the same type of plaster and painted. More titan twenty replasterings and repaintings have been counted on some walls (see figure i). Scenes appear to be religious and are concerned witlt processions, architectural features, and naturalistic and symbolic (geometric) patterns. In tlte later stages of occupation, one area of the village seems to have been set aside for cult practice and separated from tlte domestic quarters by a circumference wall. The enclosure contained two large, well-constructed rectangular buildings with axes at right angles to each other and a wealtlt of cult paraphernalia. A similar Chalcolithic enclosure was discovered at ‘Ein-Gedi. [See 'Ein-Gedi. j

Apart from tlte architectural differences, tltere is a notable Neolitltic content in the few material remains from tlte earliest levels. The pottery is very well made, both in buff and dark-faced wares, the shapes are simple, and decoration is

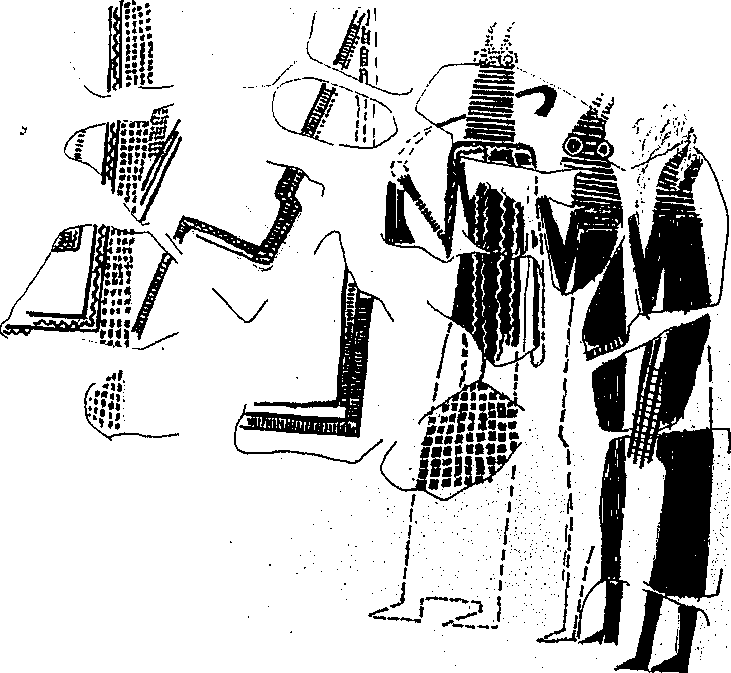

TRLBILAT EL-GHASSUL. Figure I. Wall painting. Three masked figures in ceremonial dress approach a walled enclosure. The leader carries a sickle-shaped object in his right hand. The painting is polychrome in a rich variety of red, green, yellow, white, and black. From tlie Lower Chalcolitlric levels, area III, this work (3 X i.5 m) is carbon-14 dated to approximately 4200 bce. (Courtesy J. B. Hennessy)

Comparatively rare. Apart from a thin red band of paint around the rims of a few simple subhemispherical bowls, tlte only other decoration was the occasional use of mattered slips or incised or punctated marks (on a small percentage of enclosed shapes). Burnished surfaces are very rare. In the flaked-stone industry, blades with broad denticulation and notched and serial flaked blades have their best parallels in the Neolithic B levels at nearby Jericho or the Yarmukian culmre of the Jordan Valley. [See Jericho; Jordan Valley.] Many of the forms which originate in tltese early levels continue into the succeeding building phases of the large rectangular houses. However, it is not until the uppermost two building levels that the full range of forms and decorations normally designated Ghassulian is common. By the end of the occupation, painted wares and an elaborate repertoire of sopliisticated shapes mark the end of a lengthy internal development. It is at this stage of material culture that relations with the Beersheba and coastal andjordan Val

Ley Chalcolithic settlements are most evident. [See Beersheba.]

Throughout die life of the settlement, the faunal and floral evidence suggests a mixed pastoral, agricultural, and hunting economy, witli the cultivation of wheat, barley, peas, and olives and abundant evidence of pig, goat, sheep, deer, and cattle. Another industry of some significance is suggested by the first appearance of metal in the uppermost levels of the original FBI excavations. It was to have its full development in the succeeding Beersheba Chalcolithic, with the metal ore readily available in the nearby Wadi Feinan, just to the south of the Dead Sea. [See Feinan.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Elliott, Carolyn. “The Ghassulian Culture in Palestine: Origins, Influences, and Abandonment.” Levant 10 (1978); 37-54. Good, broad coverage of the archaeological and historical importance of die Ghassulian culture.

Hennessy, J. Basil. “Preliininary Report on a First Season of Excavations at Teleilat Ghassul.” Levant i (1967): 1-24,

Hennessy, J. Basil, “Ghassul.” In Archaeology of Jordan, vol. 2, Field Reports, edited by Denys HomiJs-Fredericq and J. Basil Hennessy, pp. 230-241. Louvain, 1989. Brief coverage of the stratigraphic position of the site’s various assemblages.

Hennessy, J. Basil. “Teleilat Ghassul: Its Place in tlie Archaeology of Jordan.” In Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan, vol. i, edited by Adnan Hadidi, pp. 55-58. Amman, 1982. Argues for Late Neolithic origins for the setdement.

Mallon, Alexis, and Robert Koeppel. Teleilat Ghassul. 2 vols. Rome, 1934-1940.

North, Robert. Ghassul ig6o Excavation Report. Rome, 1961. Along with Koeppel and Mallon, the final excavation report of the PBI’s campaigns at Teleilat el-Ghassul,

J. Basil Hennessy

TELL. The term tell comes from tlie Arabic word for mound, or low hill (transliterated from Hebrew as tel). Tells form as successive levels of cities and towns are built over the ruins of tlteir predecessors. They are tlte architectural manifestations of complex civilizations and may include imposing defensive features, the trappings of institutionalized religion in the form of temple complexes, and the symbols of power displayed by elaborate palaces.

Many tells began as cities or towns circumscribed by walls, a factor that encouraged a setdement’s upward growth, rather than outward spread. The basic backbone, or structure, of a tell forms during the occupation of a site. The inhabitants construct architectural features of varying mass—city walls, terraces, ramparts, large public buildings and smaller domestic quarters. At the same time, depressions are excavated for midden deposits, storage facilities, and extracting sediment for mud brick. On the whole, these features impart an uneven topography, or cityscape, to any particular occupation phase. This variable relief is tlie source of immense stratigraphic complexity following abandonment and the overlay of subsequent city levels. Thus, archaeological structures and features from tlie same temporal strata may be at widely varying vertical levels. Anotlter complicating factor occurs because some structures fall into disuse decades before otliers, creating further difficulties for modern stratigraphic correlations.

After a site is abandoned, natural erosional forces come into play on mud-brick walls, such as rainfall and burrowing animals. The brick walls collapse and become the source of a thick matrix of decayed and reworked bricky material that appears archaeologically as deep monolithic sections of sediment. They provide most of a tell’s bulk. Through time, erosion and runoff smooth a site’s upper layers. The slopes of the tell undergo variable forces of erosion depending upon their orientation, die amount and direction of rainfall, sediment composition, and the density of vegetation. Eventually, these erosional processes lead to the mound’s dunelike shape.

Tells are a common feature in Near Eastern landscape. It has long been recognized that they contained tlte remains of past civilizations. Each generation of archaeologists working on tells has its own unique philosophical orientation: early excavators, such as Austen Henry Layard at Nimrud and Paul-Emile Botta at Khorsabad, were typically interested in retrieving curiosities and art objects from tells, using excavation techniques that appear uncontrolled by modern standards. It was only late in the nineteenth and early in tire twentieth centuries that stratigraphic control and tlte preservation of a wide variety of artifacts were perceived as mandatory in excavating a tell. A foremost pioneer of modern Near Eastern tell excavation was Flinders Petrie, who enunciated the concepts of preservation of monuments; describing and collecting all artifacts; mapping all architectural features; and fully publishing all aspects of an excavation. It was Petrie’s development of the technique of dating pottery by seriation that led to modern controlled stradgraphic excavations of Near Eastern tells.

[See also the biographies of Botta, Layard, and Petrie.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Butzer, Karl W. Archaeology as Human Ecology: Method and Theory for a Contextual Approach. Cambridge, 1982. Seethe chapter, “Site Formation” (pp. 87-97).

Davidson, Donald A. “Processes of Tel Formation and Erosion.” In Geoarchaeology: Earth. Science and the Fast, edited by Donald A. Davidson and Myra L. Shackley, pp. 255-266. London, 1976,

Lloyd, Seton. Mounds of the Near East. Edinburgh, 1963.

Rosen, Arlene Miller. Cities of Clay: The Geoarchaeology of Tells. Chicago, 1986.

Arlene Miller Rosen

World History

World History