By 2200 BP, much of Inner Asia became integrated in large-scale nomadic polities having names such as Wusun and Xiongnu which appear in the historical documents of neighboring states. These historical records often portray steppe peoples as uncultured and predatory, an enduring stereotype that masks the intricacies of nomadic cultures across Central Eurasia. To the contrary, the rise of these regional polities, some would argue, initiated a distinctive ‘steppe civilization’ which became fully developed under the imperial Mongols (800BP). The Xiongnu was a mounted, iron-, bronze-, and ceramics-producing, pastoral nomadic group under whose name the first nomadic state was organized during a period contemporary with the Qin and Han dynasties of China (2221-1800 BP). Chinese historical accounts have been the major source of information on the society, culture, and politics of the Xiongnu, though the process by which they founded their extensive polity is still little known.

Two bodies of theory explain Xiongnu emergence as occurring either by way of economic and political dependence on Chinese states or through the creation of an indigenous political economy of internal agropastoral production and long-distance sources of trade and tribute. In either case, the Xiongnu polity was constructed from diverse political and economic traditions through the integration of distinctive Inner Asian peoples. Xiongnu archaeological culture has been identified from Manchuria to Kazakhstan, and from Minusinsk to Ningxia. The heartland of the Xiongnu state was most likely in north central Mongolia and Buriatiia, along the drainages of the Selenge, Orkhon, and Tuul rivers. This region holds the major Xiongnu cemetery sites and most of the known settlements. Based on recent absolute dating, the time-span of recognizable Xiongnu occupation in this area (2400-1850 BP) precedes and postdates their appearance in the Chinese historical sources.

Xiongnu Mortuary Culture

From its beginning in the late nineteenth century, Xiongnu archaeology has consisted mainly of cemetery excavations. The mortuary perspective has provided evidence for the internal complexity of the Xiongnu state since burials reveal a hierarchy of different scales and mortuary styles. Xiongnu cemeteries range from a few burials to hundreds of graves ranging over various size groups. In Mongolia and South Siberia, these cemeteries appear to follow a four-level size/type hierarchy based on the kind of burials present and their numbers. The two main types, of Xiongnu burials are simple stone ring pit burials and large ‘dromos’ style burials distinguished by a sloping passageway used to furnish the mortuary chamber. Cemeteries can generally be grouped into four types, comprised of 5-30 ring burials, 65-110 ring burials, 200-400 ring burials, and one or more ‘dromos’ style burial having varying numbers of associated ring burials and unmarked interments. Recent DNA analysis of skeletal samples from the Burkhan Tolgoi ring burial cemetery (Mongolia), shows that these cemeteries were internally organized according to local lineage groups. In addition, variability in burial type, size, and assemblage seems to be related to a number of identity markers including gender, age, and individual status, though widespread looting in antiquity makes such analysis difficult.

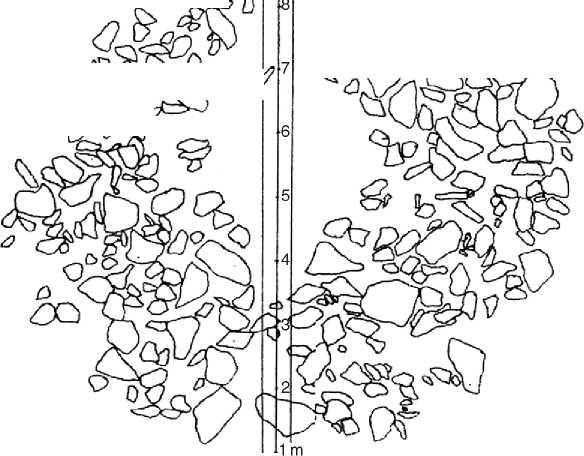

Ring burials are thought to be of local or intermediate level elite, and are identified on the modern surface by a ring of sedimented stones, 5-14 m in diameter, with a slight depression in the center (Figure 7). Below this ring feature, an oval or rectangular burial pit descends to a depth of up to 2-3 m and houses one of eight varieties of internal construction. Among these, the most common contain a wood plank coffin, or a full wooden chamber and coffin, or a chamber constructed from stone slabs, with or without a coffin. The interred individual is commonly placed in a supine position and oriented to the north. Burials are often single interments, though there are also many examples of paired burials consisting of a female and child or a male and female adult interred within a double wooden chamber. Grave furnishings include three to four main types of slow wheel constructed ceramics, compound bow pieces, bone and iron tools, iron cheek pieces and bits, semiprecious stone beads, animal style decorations, and the remains of sheep/goat, cattle, and horses. Nonlocal artifacts include Chinese lacquer ware, bronze mirror fragments, and coins as well as items from northern Siberia and western Central Eurasia. Prominent ring burial sites include Tebsh Uul and Morin Tolgoi in Mongolia and the Derestui cemetery of Buriatiia.

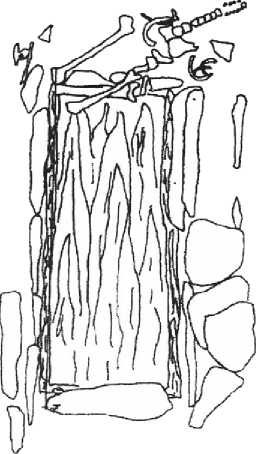

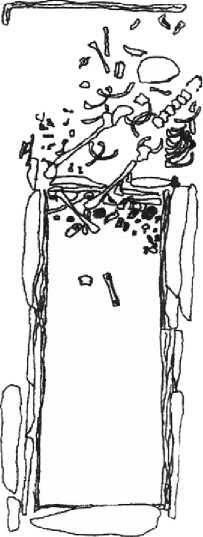

Royal Xiongnu burials are large structures and have long, sloping corridors or passageways known as ‘dro-mos/dromoi’, so-called because of their similarity to Black Sea Scythian kurgans which are thought to draw upon Greek designs. The sloping entryway is also known from Shang and Zhou tombs in China but was probably independently derived in each area as a functional way of provisioning a deep burial chamber. Several sites known to have these burials are Tsaram in southern Buriatiia, and Noyon Uul, Gol Mod, and Takhiltyn Khotgor cemeteries in central and western Mongolia. On the surface, these burials consist of a rectangular or trapezoidal earth and stone platform mound up to 30 m on a side and 1-2 m in height. The tombs are oriented north-south and on the south side appears the dromos entryway up to 22 m in length and often with internal wooden structures and artifacts included in the passage. The burial pits of these tombs reach 10 m or more in depth and the construction overlying the chamber consists of soil, stone, and wooden layers, as well as partitions built of articulated logs. The burial chamber includes an inner and outer wooden enclosure of hewn timbers and wooden planks. Within the innermost chamber, a wooden coffin holding an interred individual is found, though disruption from pillaging has often destroyed the internal contexts of these sites.

The artifact assemblages of the Noyon Uul dromi burials, excavated in the 1920s, are exceptionally well known due to the preservation of organic materials by water seepage into burial chambers. The Noyon Uul tombs were richly furnished with large ceramic vessels, felt carpets, wooden carvings, clothing, silks,

Figure 7 Plan of an excavated Xiongnu period ring burial with internal stone slabs, wooden coffin planks, and human skeletal fragments in disarray from early pillaging, Egiin Gol valley, Mongolia. Originally published in: T. Torbat, Ch. Amartuvshin, and U. Erderebat (2003) Egiin Goly sav nutag dakh’ arkheologiin dursgaluud. Ulaanbaatar: Mongolian Institute of Archaeology, p. 256.

Jade objects, bronze mirrors, lacquer containers, and horse riding equipment. Animal remains included horse, cattle, camel, and deer, and domestic grain was recovered as well. Recent excavations at the Tsaram and Gol Mod cemeteries have both produced the complete remains of two-wheeled horse drawn carriages of Han dynasty design. Such elite contexts provide important evidence for a high degree of status differentiation among individuals within the Xiongnu polity. The excavations at the site of Tsaram have provided further evidence for status differentiation in the form of eight individual male interments arranged according to age around a central dromos burial, suggesting a pattern of intentional human sacrifice. Such monumental burial sites have been discovered throughout central Mongolia and southern Buriatiia. The Inner Mongolian sites of Xigoupan and Budonggou, and Daodunzi of Ningxia are contemporary with, and share some affinities with, the Xiongnu mortuary culture of Mongolia and Siberia, though no sites similar to the royal Xiongnu tombs have been discovered.

Xiongnu Settlement Archaeology

The geographic range of Xiongnu archaeological culture encompasses a great diversity of ecological environments including desert, oases, steppe, and the forest steppe regions of Siberia. Locales vary as to the availability of productive soils, water, protected winter pasture, and other critical resources for agricultural and pastoral subsistence alike. Historical texts describe the Xiongnu as specialized mobile pastoralists, however, the extent to which specialized herding, transhumance, and settled cultivation were combined as subsistence strategies within the larger state is still not clear. Nor is it clear how production varied chronologically or whether differences in subsistence were the result of adaptations to local environment or whether the Xiongnu economy was purposefully differentiated to support the needs of the state elite. The Xiongnu settlement record gives strong evidence that the productive economy within the Xiongnu polity was more complex and differentiated than historical accounts would suggest. Excavations of the Ivolga settlement, occupied from 2300-2100 BP, indicate that some portion of the Xiongnu population was settled and engaged in cultivation, craft production, and herding.

Ivolga was a fortified settlement located on a terrace above an older course of the Selenge river in the forest-steppe of Buriatiia. A large cemetery of unmarked graves contemporary with settlement was found nearby. The settled area was approximately 7.5 ha in size and included a system of ditches, earthen ramparts, and a palisade. A portion of the settlement was excavated revealing 51 dwellings, a number of storage structures, and possible animal pens. Most of the dwellings were found to be semi-subterranean houses ranging from 9-46 m2 in area and having rectangular pits covered by a pitched roof with a sophisticated fireplace and heating system. A single structure near the center of the settlement was much larger in area (150 m2) and built on the ground surface, suggesting some differences in function or residential status. Ivolga inhabitants engaged in the cultivation and storage of grain and semi-specialized craft manufacture including iron and bronze metallurgy and ceramic production. A range of Xiongnu material culture was recovered from the site such as metallic items, bronze mirror fragments, split bone arrow points, compound bow pieces, sickles, grinding stones, and digging tools. Archaeologists discovered millet, barley, and wheat grains and a faunal assemblage of sheep/goat, horse, cattle, yak, camel, and several wild species.

These patterns of production are similar at the Dureny settlements in Buriatiia, south of Ivolga. Botanical evidence for wheat and millet use at seasonally occupied ‘pastoral’ campsites of the Xiongnu in the Egiin Gol valley appears at an early date and further supports the hypothesis of a more differentiated regional economy. Recent research on the Wusun period in southeastern Kazakhstan (2300-1800 BP) at the habitation site of Tuzusai shows a shift in agropastoral investment towards a greater emphasis on producing millet, wheat, and even rice. Researchers argue that this period of more intensive agriculture may have been linked to political consolidation under the Wusun polity and the need to increase and control critical resource production. In the Xiongnu case, such control may have been accomplished by the construction of walled centers, such as Ivolga. Recent reports of new Xiongnu walled settlements in Mongolia have increased the number of such ‘central places’ to between 15 and 20 sites. These settlements have rectangular earthen walls enclosing areas from 2 to 13 ha, traces of internal structures, and many are spatially integrated within networks of associated cemeteries. Though more work is still needed, the archaeological record shows a preliminary pattern across Inner Asia of large-scale political organization associated with regional economies involving both mobile and sedentary sectors.

Steppe Civilization and Empires to Come

As the archaeological record shows, Inner Asian peoples, from a very early time, developed cultural traditions that functioned within an environment of movement and social diversity. The Xiongnu polity was the first experiment in applying these traditions to the creation of an extensive political organization across most of Inner Asia. This experiment was surprisingly successful, lasting almost 400 years before the first state itself dispersed across the steppe. The Xiongnu established a model for politics that would be remembered, emulated, and elaborated over the next two milleniums as numerous steppe empires mobilized their peoples and expanded across Eurasia. In the process of building their distinct empires, the Turks, Uighurs, Khitan, and medieval Mongols who followed upon the Xiongnu, integrated tremendous swathes of the Old World and created cultural, economic, and political innovations that would become the legacy of a genuine steppe civilization.

See also: Animal Domestication; Asia, Central, Steppes; Asia, East: China, Neolithic Cultures; China, Paleolithic Cultures; Chinese Civilization; Asia, Northeast, Early States and Civilizations; Plant Domestication; Political Complexity, Rise of; Siberia, Peopling of.

World History

World History