The relationship between sickle-cell disease and malaria provides us with a neat example of a genetic adaptation to a particular environment, but we can also examine continuous traits controlled by many genes in terms of adaptation to a particular environment. However, this tends to be more complex. Because specific examples of adaptation can be difficult to prove, scientists sometimes suggest that scenarios about adaptation may resemble Rudyard Kipling’s fantastic “Just So Stories.”

Anthropologists study biological diversity in terms of clines, or the continuous gradation in the frequency of a trait or allele over space. The spatial distribution or cline for the sickle-cell allele allowed anthropologists to identify the adaptive function of this gene in a malarial environment. Clinal analysis of a continuous trait such as body shape, which is controlled by a series of genes, allows anthropologists to interpret human global variation in body build as an adaptation to climate.

Generally, people long native to regions with cold climates tend to have greater body bulk (not to be equated with fat) relative to their extremities (arms and legs) than do people native to regions with hot climates, who tend to be relatively tall and slender. Interestingly, tall, slender bodies show up in human evolution as early as 2 million years ago. A person with larger body bulk and relatively shorter extremities may suffer more from summer heat than someone whose extremities are relatively long and whose body is slender. But the bulkier person will conserve needed body heat under cold conditions because this body type has less surface area relative to volume. In hot, open country, by contrast, people benefit from a long, slender body that can get rid of excess heat quickly. A small, slender body can also promote heat loss due to a high surface area to volume ratio.

In addition to these sorts of very long-term effects that climate may have imposed on human variation, climate can also contribute to human variation by influencing growth and development (developmental adaptation). For example, some of the physiological mechanisms for withstanding cold or dissipating heat have been shown to vary depending upon the climate an individual experiences as a child. Individuals spending their youth in very cold climates develop circulatory system modifications that allow them to remain comfortable at temperatures people from warmer climates cannot tolerate. Similarly, hot climate promotes the development of a higher density of sweat glands, creating a more efficient system for sweating to keep the body cool.

Cultural processes complicate studies of body build and climatic adaptation. For example, dietary differences particularly during childhood will cause variation in body shape through their effect on the growth process. Another complicating factor is clothing. Much of the way people adapt to cold is cultural rather than biological. For example, Inuit peoples of northern Canada live in a region that is very cold for much of the year. To cope with this, they long ago developed efficient clothing to keep their bodies warm. Thus the Inuit and other Eskimos are provided with an artificial tropical environment inside their clothing. Such cultural adaptations allow humans to inhabit the entire globe.

Some anthropologists have suggested that variation in certain features, such as face and eye shape, relate to climate. For example, biological anthropologists once proposed that the flat facial profile and round head, common in populations native to East and Central Asia, as well as arctic North America, derive from adaptation to very cold environments. Though these features tend to be more common in Asian and Native American populations, considerable physical variation exists within each population. Some individuals who spread to North America from Asia have a head shape that is more common among Europeans.

In biological terms, evolution is responsible for all that humans share as well as the broad array of human diversity. Evolution is also responsible for the creation of new species over time. Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal has said, “Evolution is a magnificent idea that has won over essentially everyone in the world willing to listen to scientific arguments.”25 We will return to the topic of human evolution in chapters that follow, but first we will look at the other living primates in order to understand the kinds of animals they are, what they have in common with humans, and what distinguishes the various forms.

Clines Gradual changes in the frequency of an allele or trait over space.

1. Have scientific understandings of the human genetic code and technologies such as DNA fingerprinting challenged your conception of what it means to be human? How much of your life, or of the lives of the people around you, is dictated by the structure of DNA?

2. The social meanings of science can test other belief systems. Is it possible for spiritual and scientific models of human nature to coexist? How do you personally reconcile science and religion?

3. The four evolutionary forces—mutation, genetic drift, gene flow, and natural selection—all affect biological variation. Some are at work in individuals while others function at the population level. Compare and contrast these evolutionary forces, outlining their contributions to biological variation.

4. The frequency of the sickle-cell allele in populations provides a classic example of adaptation on a genetic level. Describe the benefits of this deadly allele. Are mutations good or bad?

5. Why is the evolution of continuous traits more difficult to study than the evolution of a trait controlled by a single gene?

Alper, J. S., et al. (Eds.). (2002). The double-edged helix: Social implications of genetics in a diverse society. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

This collection of essays examines the social consequences of the new genetics in topics ranging from the discovery of a “gay” gene to the social history of the unsuccessful genetic testing programs for sickle-cell disease among African Americans.

Berra, T. M. (1990). Evolution and the myth of creationism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Written by a zoologist, this book is a basic guide to the facts in the debate over evolution. It is not an attack on religion but a successful effort to assist in understanding the scientific basis for evolution.

Eugenides, J. (2002). Middlesex: A novel. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

This fascinating novel explores the lives of a family carrying a recessive allele that results in hermaphroditic phenotype in the third generation. It demonstrates the intersection of genetics and culture, deals with age-old questions of nature versus nurture, and explores the importance of the cultural meaning given any phenotypic state.

Gould, S. J. (1996). Full house: The spread of excellence from Plato to Darwin. New York: Harmony.

In this highly readable book, Gould explodes the misconception that evolution is inherently progressive. In the process, he shows how trends should be read as changes in variation within systems.

Rapp, R. (1999). Testing women, testing the fetus: The social impact of amniocentesis in America. New York: Routledge. This beautifully written, meticulously researched book provides an in-depth historical and sophisticated cultural analysis, as well as a personal account of the geneticization of reproduction in America. It demonstrates the importance of cultural analyses of science without resorting to an antiscientific stance.

Ridley, M. (1999). Genome: The autobiography of a species in 23 chapters. New York: HarperCollins.

Written just as the mapping of the human genome was about to be announced, this book made The New York Times bestseller list. The twenty-three chapters discuss DNA on each of the twenty-three human chromosomes. A word of warning, however: The author uncritically accepts some ideas (one example relates to IQ). Still, there is much food for thought here.

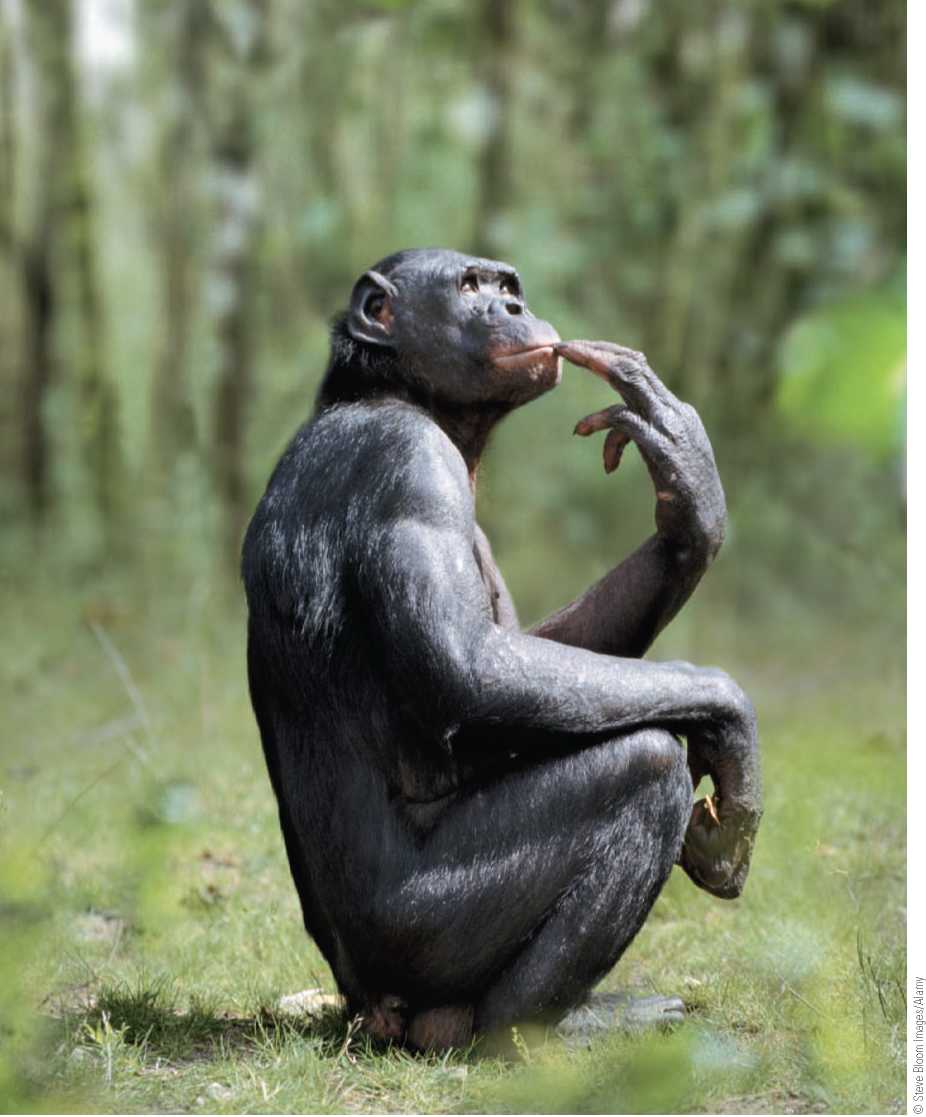

Challenge Issue Other primates have long fascinated humans owing to our many shared anatomical and behavioral characteristics. Our similarities, especially to the other great apes such as this bonobo, can be readily seen not just in our basic body shape but also in gestures and facial expressions. Our differences have had devastating consequences for our closest living relatives in the animal world. No primates other than humans threaten the survival of others on a large scale.

Over a decade of civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the natural habitat of bonobos, and genocide in neighboring Rwanda have drastically threatened the survival of this peace-loving species. These violent times have prompted the hunting of bonobos to feed starving people and the illegal capture of baby bonobos to be sold as pets. In the 21st century, humans face the challenge of making sure that other primates do not go extinct due to human actions.

World History

World History