The Issue of ‘Authenticity’

At Chaco Canyon in the mid-1990s, Christine Finn examined the quandary of NPS employees in dealing with ritual objects left at Casa Rinconada. In her essay, she raises the issue of ‘authentic’ use of an ancient site, and asks whether it is possible to discriminate one use as more worthy than another. The Native American community argued their right through inheritance or continued use: How might more recent visitors, such as twenty-first century New Age followers, claim their right to use the site? Is their use, for ritual purposes, an expression of care and understanding, or does it mark a lack of consideration for earlier claims on the site? Is the site, or the significance of the encompassing landscape, the main issue? Chaco Canyon, she points out, as a celebrated heritage complex located in the desert US Southwest, continues to be a valuable resource to Native Americans while also becoming a ceremonial center for New Age followers, who were, ironically, in part inspired by Native American knowledge.

As this case exemplifies, and as is reflected in the conclusions of the Charleston Declaration, further discussions are needed on the concept and meaning of ‘authenticity’ in interpretation. Traditional attitudes that focus on static, material authenticity will need to be replaced with more conditional and contextual definitions shaped by acknowledgement of dynamic processes of cultural change and diversity rather than judgments based on fixed criteria. Definitions of authenticity must be tempered or guided by local and community-based, inclusive analyses. Any analysis model for authenticity should reflect and represent multiple perspectives on what is authentic or ‘true’ about a site or place and should provide a roadmap for practical solutions. The nature and qualifications of ‘experts’ on authenticity should reflect the diversity of cultural affiliations and values attributed to the site, which, in turn, should be periodically reviewed and reassessed.

Toward More Inclusive Interpretation

In heritage management, some of our most serious challenges involve defining and applying universal principles of interpretation. In present-day discussions and debates about interpretation standards, the subject of inclusiveness tends to be one of the more contentious and problematic issues. There are many, often overlapping, roadblocks to inclusiveness involving cultural, political, economic, and social factors. It can seem hopeless in a wide variety of sites and settings: can Jerusalem, for example, ever be interpreted in a way that we can describe as inclusive to all, or even a majority, of stakeholders?

When we contemplate the challenges posed by the study and commemoration of heritage places within modern multicultural societies, we step into a complicated maze of terminology and semantics centered on international debates about relevance and conscience as well as cross-cultural and international priority and appropriateness. We come to the table with developing, and sometimes divergent, assumptions and purposes for site commemoration and treatment. While no country or region in the world practices or exhibits multiculturalism in the same manner, most of the these conversations occur in countries from the Western cultural tradition, or, at least, the terminology used in these discussions stems from the predominately Western ideas of equal treatment, ethnic sensitivity, and accountability for multiple points of view that are constantly and openly debated. Many of the categories used in heritage site management, such as national park, national monument, and world heritage site, are notions of commemoration originating in the West (see World Heritage Sites, Types and Laws). This is mentioned here so as not to forget that, as we enter into discussions of international and universal relevance, we need to be cautious in avoiding terminology that can appear, to a non-Westerner, to be patronizing and insensitive.

Multiculturalism is one of those terms that are difficult to describe definitively, but it is important in our discussions here in that it describes the general sociopolitical environment that is necessary for public policy in managing cultural diversity in multiethnic societies, stressing mutual respect and tolerance for cultural differences within a country’s or region’s borders. As a policy, multiculturalism emphasizes the unique characteristics of different cultures, especially as they relate to one another within national boundaries. Multiculturalism is a view, or policy, that immigrants and other groups should preserve their cultures with the different cultures interacting peacefully within one nation. This has been the official policy of Australia, Canada, and the UK. Multicultur-alism has been described as preserving a ‘cultural mosaic’ of separate ethnic groups, and is contrasted to a ‘melting pot’ that mixes them, the United States commonly being given as an example of a melting pot. Some use the term multiculturalism differently, describing both the melting pot, and the ‘cultural mosaic’ condition, such as in Canada, as being multicultural and refer to ‘pluralistic’ versus ‘particular-ist’ multiculturalism. Pluralistic multiculturalism, similar to the melting pot concept, views each culture or subculture in a society as contributing unique and valuable cultural aspects to the whole culture. Particularist multiculturalism is more concerned with preserving the distinctions between cultures. Probably no country falls completely into one, or another, of these categories (see Culture, Concept and Definitions).

The nature of the reality of multiculturalism in any one country or region affects public policies and attitudes about inclusive heritage interpretation and where to focus the discussions; that is, what are the messages, and to whom are the messages directed?

Fundamental Questions

In our deliberations regarding who owns the past and what constitutes inclusive public interpretation, we can couch our discussions within the framework of attempting to answer some fundamental questions. While present and future deliberations will not easily resolve these questions, they certainly encompass many of the key issues.

First, what constitutes an ‘inclusive’ public interpretation of heritage? The Ename Charter on Interpretation (Table 1) defines ‘inclusiveness’ as that which seeks to ensure that the interpretation of a cultural heritage site is not merely a carefully scripted presentation prepared by outsiders, but should instead actively involve the participation of associated communities and other stakeholders. In all aspects of site commemoration and site management, whether these are interpretive programs, exhibits, physical maintenance activities, or the effects of heritage tourism, according to the charter, an interpretation program must be seen as a community activity rather than something imposed by persons or institutions perceived to be outside the community. ‘Community’ in this sense is simply a group or class having common interests, or likeness or identity. Communities include educational, professional, academic, governmental, descendant, and local. Communities are not discrete in that they can and do overlap. For example, members of a descendant community may also be part of the educational and the professional communities. In discussions of inclusiveness, our ideal for communities is that they be involved in participatory education and public interpretation where members of a community actively participate in developing, carrying out, delivering, or otherwise producing the program or elements of the program or interpretive product.

The second question we might pose is ‘‘Does the term ‘inclusive’ connote democratic or equal treatment? How does it relate to, appeal to, and be available to, broad masses of people?’’ If we accept the assumption that some form of multiculturism is a necessary backdrop for inclusiveness, our approaches to commemoration and public interpretation should follow an objective process that seeks to identify the attributes, or values, inherent in the resource that make them important to people and therefore worthy of protecting, preserving, and celebrating.

Third, we might ask, in multicultural societies, how are standards of significance and authenticity promulgated and agreed upon, and how are they effectively formalized while accommodating multiple points of view? One corollary question is, once commemoration standards are formalized in terms of management strategies and oversight procedures, how are the values of immigrant and minority communities, as well as evolving values of the ‘majority’ addressed and accommodated within the identification-commemoration process? A second corollary question is, are formally managed monuments and sites a reflection of a timeless ideal or a changing reality, and can these purposes coexist?

Public interpretation treatments worldwide run the gamut for tendencies of inclusiveness and exclusiveness. What does a Palestinian, or Palestinians as a group, believe as authentic and therefore worthy of protection and commemoration? How does this compare in terms of commonality of commemoration, sense of place and setting, etc., with the heritage values of Israelis for the same territory or site? Can divergent communities in terms of values and opinions on commemoration ever arrive at a consensus, or even develop a constructive dialogue, about the rights of inclusion in heritage interpretation and site management?

Inclusiveness through Values-based Management

One approach that seems to result in more democratic and far ranging treatments, involving a comprehensive assessment based on input from a broad range of stakeholders, is what has been termed ‘values-based management’. Values-based management aids inclusiveness by providing a mechanism for accountability for the totality of values and significance attributed to a site or set of sites. ‘Values’ in this sense relate to tangibles and intangibles that define what is important to people. In all societies, a sense of well-being is associated with the need to connect with and appreciate heritage values. An understanding of how and why the past affects both the present and the future contributes to people’s sense of well-being. In heritage management, we articulate ‘values’ as attributes given to sites, objects, and resources, and associated intellectual and emotional connections that make them important and define their significance for a person, group, or community. Practitioners of values-based management strive to identify and take these values into account in planning, physical treatments, and public interpretation efforts. In theory, values-based management, if thoroughly and impartially executed, will result in more democratic and inclusive interpretations by accounting for the values of all stakeholders. This is the ideal.

Some notable examples of values-based management were published in a series of studies sponsored by the Getty Institute in 2003. And there are many more examples from the US and elsewhere: Chaco Canyon National Historic Park in the United States;

Port Arthur World Heritage Site, Tasmania, Australia; and Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site in the UK.

Although differing ethnic groups will not agree on the meaning of, or share the same perspective toward, concepts of value, all people who ascribe meaning and significance for a site will relate to concepts of value in some significant way. Perhaps an extension of the values-based approach that can facilitate more inclusive interpretation is to develop mechanisms of identifying more broadly defined value categories. More broadly defined concepts of value would aid inclusiveness by making meanings accessible and relevant to wider communities of stakeholders.

It seems that many of the contested issues surrounding values’ assessments are rooted in divergent concepts of authenticity. Authenticity involves factors that ascribe values or meanings that make something real and not an imitation; they ascribe concepts of ‘truth’ or legitimacy for a society, group, community, or individual, perhaps a topic for another future colloquium, and, indeed, ICOMOS.

Beyond Recitation: The Application and Art of Interpretation

Effective interpretation: Fostering audience links to resource meanings and universal concepts Another possible avenue toward a more inclusive and internationally relevant public interpretation of heritage is to consider the utility and development of universal values and concepts that can provide the greatest degree of relevance and meaning to the greatest number of people.

A major goal of interpretation is to provide links for audiences between tangibles and intangibles and to place the audience or visitor in relationship with broad meanings. The NPS IDP, discussed earlier in this article, has identified links to universal concepts as key to effective interpretation in all modes of delivery. IDP describes universal concepts as intangible resources that almost everyone can relate to, that is, universal intangibles. While not all people are likely to agree on the meaning of or share the same perspective toward a universal concept, according to the IDP philosophy of interpretation, all audiences can relate to the concept in some meaningful way. For example, the rocks (tangible) of Yosemite National Park tell many stories of beauty, danger, and mystery (intangible). Universal concepts make meanings accessible and the resource relevant to widely diverse audiences. They do not always have to be explained to be experienced or understood. Approaches and techniques for presenting universal concepts will differ from one type of resource to another. In all modes of delivery, the interpretive product should capture and illustrate the tangible to intangible/universal concepts.

According to IDP, the interpretive product should include a variety of universal concepts such as time, change, tranquillity, peace, safety, security, shelter, and solitude. It should be appropriate for the audience and provide a clear focus for their connection with the resource by demonstrating the cohesive development of a relevant idea or ideas, rather than relying primarily on chronological narrative or a series of related facts. It should provide opportunities for audiences to make both intellectual and emotional connections to resource meanings by using analogies, comparisons, word pictures, and other methods to link tangibles and intangibles. According to IDP, ‘‘the visitor is sovereign’’ in terms of forming his or her own intellectual and emotional connections with meanings and significance inherent in the resource. The interpretive product should serve as a catalyst in creating opportunities for the audience to form these connections (NPS IDP 2006).

Interpretation as a mechanism for resource sustainability Many of the established principles for interpretation in the United States and internationally stem from the writing and philosophy of Freeman Tilden. Tilden defined interpretation as an educational activity that aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects by first-hand experience and illustrative media, rather than to simply communicate factual information. Freeman’s six principles emphasized relevance to the experience of the audience and interpretation as a teachable art form. According to Tilden, the chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation, and must address itself to the whole person rather than any phase. Tilden advocated what we would describe today as a ‘layered’ approach to interpretation that takes into account the perspectives of a variety of audiences differentiated by age, sociocultural background, and other factors. Later advocates have built on the foundations of Tilden and applied postmodern theoretical approaches. Jon Kohl, for example, defines interpretation in terms of ‘‘a ‘paradigm’, a deeply embedded set of beliefs that together form a story or worldview.’’ To Kohl, each culture has a story that explains its people’s creation, significance, and destiny. This set of beliefs directs how they relate to resources. Kohl advocates expanding the scope and ultimate goal of interpretation beyond conservation goals toward an integration of ‘‘deep stories’’ that ‘‘carry it across the divide to conservation in the short-term and sustainability of natural and cultural resources in the long.’’ For interpreters, he says, these changes will first be felt in conservation, a sector of sustainable resource management, and then later for sustainability issues in general.

Kohl believes that effective interpretation in the future will involve a paradigm shift that rewrites the worldview script by interpreting new ideas and meanings in order to move society toward sustainability.

Interpretation through inspiration and cognitive connection Many cultural heritage specialists today are not content to rely solely on traditional methodologies and analytical techniques in their attempts to reconstruct human history and bring it to life for people. They want to venture beyond utilitarian explanations and explore the interpretive potential of cognitive imagery that archaeological information and objects can inspire. They realize the value and power of artistic expression in helping to convey archaeological information to the public. Archaeologists are increasingly concerned with how the past is presented to, and consumed by, nonspecialists. They want to examine new ways of communicating archaeological information in educational venues such as national parks, museums, popular literature, film and television, music, and various multimedia formats.

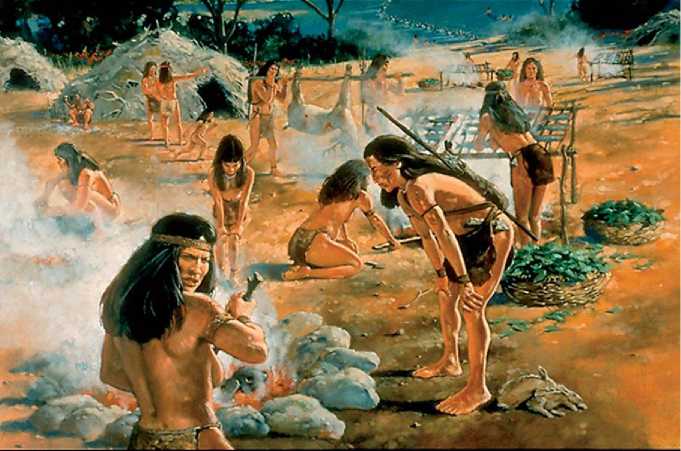

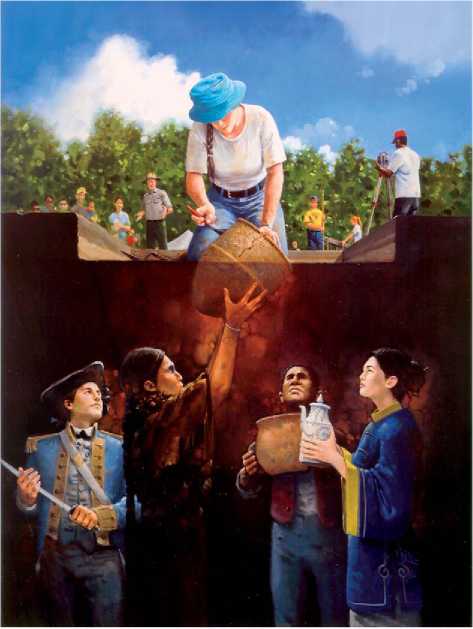

Archaeology and archaeologically derived information and objects have inspired a wide variety of artistic expressions ranging from straightforward computer-generated reconstructions and traditional artists’ conceptions to other art forms such as poetry and opera. Although some level of conjecture will always be present in these works, they are often no less conjectural than technical interpretations and have the benefit of providing visual and conceptual imagery that can communicate contexts and settings in compelling ways. Two such interpretive formats, two-dimensional paintings and popular history writing, are used by the NPS as public interpretation and education tools (Figures 2 and 3).

Interpretation in popular history writing Today, many public archaeologists have come to agree that ‘both’ quality research and the public interpretation of research findings are indispensable outcomes of their work. After all, is not the ultimate value of archaeological studies not only to inform but also ultimately to improve the public’s appreciation of the nature and relevance of cultural history? This improved appreciation results in an improved quality of life for all persons. Exhibits and popular history writing are two of the most effective techniques for public interpretation of archaeology. To be successful, both techniques must not only inform but entertain. The goals are to connect, engage, inform, and inspire, resulting in a lasting and improved appreciation of the resource.

Too often, among the flood of reports and artifacts that have come from cultural heritage studies, archaeologists and cultural heritage managers lose sight of the purpose of the compliance process, which is to provide public enjoyment and appreciation for the rich diversity of past human experiences. An important, and some would say the ‘most’ important, outcome of mitigation programs is the production of publications, programs, and exhibits that provide public access to research findings. For example, an important outcome of the Richard B. Russell (RBR) CRM program of the US Army Corps of Engineers, a major reservoir and dam project of the 1980s, was the

Figure 2 ‘‘Sara’s Ridge Archaic Site.’’ Interpretive oil painting by Martin Pate, based on archaeological site information and base map, Richard B. Russell Dam and Reservoir, Georgia and South Carolina. Image courtesy Southeast Archeological Center, National Park Service.

Figure 3 “Unlocking the Past.’’ Oil painting by Martin Pate. The painting is meant as a metaphor for the theme and topics of the Unlocking the Past outreach project that discussed the nature of historical archaeology in North America. The image is being used by the Society for Historical Archaeology as a logo for its education and outreach efforts.

Production of publications and exhibits that provided public access and interpretation of the findings of the RBR studies. In the production of the RBR popular history volume, Beneath These Waters, the NPS and the Corps jointly produced a popular account that was both informative and entertaining. In preparing Beneath These Waters, the NPS chose a team of professional writers adept at the art of effectively translating technical information for the lay public. The writers, not formally trained in archaeology or history, faced distinct disadvantages in taking on the task of writing the book. As they pored over the various technical archaeology and history reports, however, they realized that this initial detachment from technical know-how had given them an important advantage in writing a popular history. They could apply objectivity in reviewing the project and its results, unencumbered by the predictable baggage of professional biases, cultivated styles, and emotions attached to a project of this magnitude and importance. The writers’ task was to take the results of two decades of research, strip them to the essentials, and reclothe them for a general audience without losing the fundamental integrity of the original material. The universal praise of Beneath These Waters from the educational, scientific, and local communities was a testament to the success of the book in providing informational access to the research findings.

The Challenges of Heritage Tourism

Another current and ever-growing challenge that will affect the inclusiveness of heritage management and interpretation is the juggernaut of tourism. By definition, heritage tourism is collaboration between conservationists and commercial promoters. In heritage tourism, our goal is to harness people’s fascination and sense of connection to the past and turn it into a commodity. It is often an uneasy association because the motives of these respective groups are not always compatible. While there is general recognition that heritage tourism can work to promote preservation of communities’ historic and cultural resources, and also educate tourists and local residents about the resources, the resulting effects are not always viewed as beneficial, especially from those of us on the conservationist side of the fence. Nevertheless, because heritage tourism is a growth industry in almost every part of the world, the issues it conjures up - good and bad - must be addressed.

Globalization and global tourism are changing our world in ways that we are just beginning to understand. Heritage tourism, with its ties to the currents of rapidly evolving global economies, is causing increasing needs and demands for cross-cultural and international communication and interdisciplinary training. Greater importance is being placed on transferable skills such as the application of interdisciplinary approaches, writing for both academic and nonacademic audiences, oral presentation, and experience with multimedia packages.

Heritage tourism run amok - when the relationship lacks conservation-driven decision making and objectively derived values assessments - threatens or limits the goal of inclusiveness in interpretation by rendering community and other stakeholder involvement superficial. Interpretation of the meaning of sites is inherently important to the conservation process and therefore plays a defining role in conservation/tour-ism interactions. Those of us whose primary goals and interests are conservation should be determined that our values and standards in this relationship are not compromised or diminished.

World History

World History