Studies of ancient court traditions and etiquette by Edo period (1603-1868) literati provided the foundation for the introduction of modern archaeology to Japan during the late nineteenth century by E. S. Morse. Even before this the concentration of ancient capital remains in the Kinai region (the Nara-Osaka-Kyoto region) of Honshu led interested Edo scholars to conduct studies there, ranging from the measurement of tombs to the topographic reconstruction of the Heijo Palace site. The subsequent development of protohistoric and historic period archaeology in Japan uses a historiographical approach like that of Korea and China. Post-World War II Japan saw the de-mythologizing of the imperial house, which gave Japanese scholars new freedom to question the textual picture of Japan as having Been ruled by a single dynasty from the start of time. However, ideology still influences archaeology, as seen in the current enforcement of the late eighteenth-century ban by the Imperial Household Agency

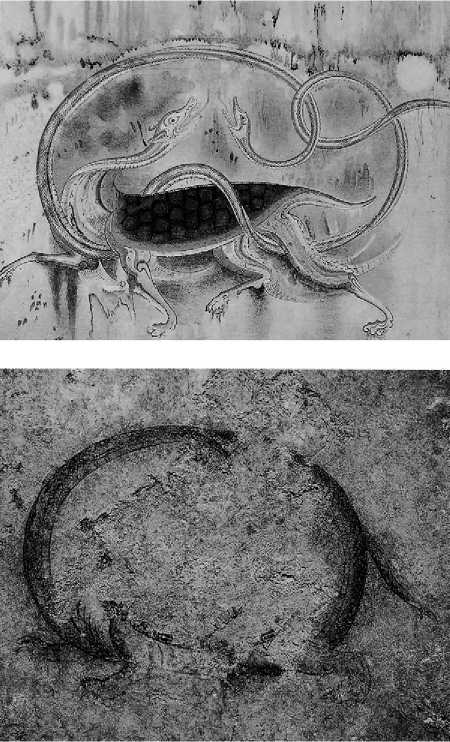

Figure 9 Tortoise and snake tomb murals from (top) the Great Tomb at Kangso, near Pyongyang, North Korea, early seventh century; (bottom) from the Takamatsu Tomb, Nara Prefecture, Japan, late seventh to eighth century.

On the excavation of over 100 tombs predating the eighth century because they may contain the remains of emperors or other once-sacred royals. Japan’s rapid postwar economic development in tandem with strong archaeological protection laws ensure that much data pertaining to the historic period has been, and continues to be recovered.

William Farris has noted several topics that dominate historical archaeological research in Japan: the question of Yamatai, the relationship between ancient Japan and Korea, the influence on Japan’s urban development of the adoption of the Chinese city model in the Nara period (710-794), and the general influence on indigenous Nara period culture of adopting many Chinese political and economic institutions.

Yamatai, a protohistoric polity ruled by Queen Himiko known from the Chinese Wei Shu, has been the focus of scholarly debate for centuries. The Wei Shu gives directions to Yamatai, but different interpretations lead to locations either on Kyushu or in Kinai, each with its own camp of supporters and distinctive political overtones. Before 1945, the Kinai position signified acceptance of the ancient origins for the imperial family with its ties to the Kinai region, while the Kyushu position signified rejection of these origins. Yamatai’s entry into general public discussion and the various overtones it has taken on there have made many scholars retreat from the debate. Although textual evidence for this debate is exhausted, and no conclusive archaeological evidence has yet come to light, the archaeological work done in the quest to answer this question has significantly contributed to knowledge of late Yayoi period (c. 400 BCE-CE 300) society.

Since late prehistoric times Japan, Korea, and China have interacted with varying intensity and directions of influence. Many elements that contributed to Japan’s early development were introduced from China via the Korean Peninsula after first undergoing Korean acculturation. Japan has always admitted its cultural debt to China, but the extent of its debt to Korea did not gain acceptance until the later twentieth century (Figure 9). The traditional view of early Japan based on the Nihon Shoki and fueled by imperialistic goals was that Yamato (c. fourth to seventh century) played a dominant role among the Korean states from its outpost in Mimana, a colony established in the southern Peninsula. Critical postwar re-interpretation included Egami Namio’s ‘Horserider theory’ in which the islands were suddenly invaded by militaristic, horse-riding nomads from North Asia in the fourth century, who crossed

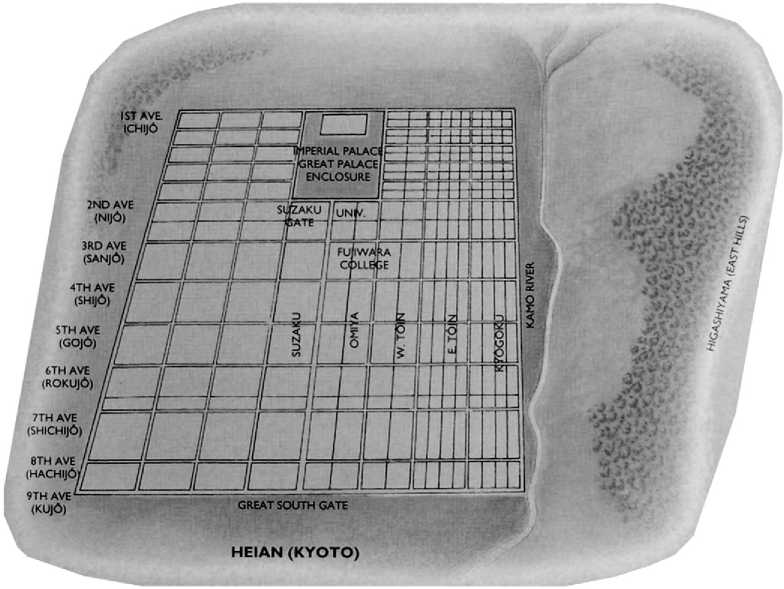

Figure 10 Plan drawing of the Heian period capital of Heian (Kyoto), Japan.

The Korean Peninsula, entered Japan, and established kingdoms in both. Postcolonial and civil war Korean reaction to these theories was intense and included many archaeological investigations. This work, along with much by Japanese archaeologists, indicates the extent of cultural imports from the Peninsula to the Archipelago, such as iron and improved pottery technology, horses and mounted warfare, new burial methods, use of gold and silver ornaments, writing and mathematics, silk weaving, advanced bureaucratic methods and organization, Buddhism and Buddhist architecture, and Chinese-style law. It has also shown that Yamato presence on the Peninsula is not indicative of a colony, and that the horse trappings contained in fourth-century tombs forming the foundation for the ‘Horserider theory’ date to the end of the century, later than the phenomena the theory is meant to explain.

Excavation of early capital cities and palaces in the Kinai region such as Fujiwara, Nara, Naniwa,

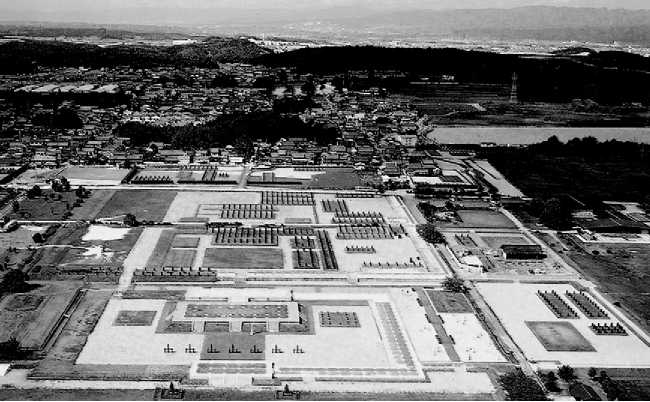

Figure 11 Overview of Nara City and the Nara Palace, Japan.

Figure 12 The Second Great Imperial Hall and Residence at Nara, Japan.

Nagaoka, Heian, and several smaller ones, as well as of their associated Buddhist temples and other remains has been an important focus of historical archaeology. New textual materials - wooden slips used in bureaucratic record-keeping - were found at many of the sites and have shed much light on the nature of pre-Nara and Nara period society and government (see Figure 1). Research has also shown the Japanese adaptation of the Chinese gridded-city model for their own needs, and clarified chronological sequences of capital-city building and developments in infrastructure (Figure 10). Architectural features, facilities, or wooden slips have even identified several structures by their function, such as the Sake Bureau compound at Nara. Details in the palace layouts indicate the organization of rule, and transportation and field systems have also been identified (Figures 11 And 12). While these investigations are not politically charged like the debates on Yamatai and Korean influences, archaeology has uncovered the dissonance between the grand images of the royal courts found in the texts and the reality of imperial rule and its ability to organize labor and finances for its projects. These circumstances are seen in the re-use of roof tiles and beams from the old palaces and capitals in new buildings, and the phased or even unfinished nature of some construction due to labor shortages.

See also: Asia, East: Chinese Civilization; Asia, Northeast, Early States and Civilizations; Historical Archaeology: As a Discipline; Methods; Writing Systems.

World History

World History