Human settlement in the southwest Pacific was characterized by several unique features. Most of the area has been occupied by humans very briefly in comparison with many other areas of the world. All areas outside of Australia, Papua New Guinea, and parts of the Solomon Islands (so-called ‘near-Oceania’) have been habited for <3500 years (see Oceania: Australia). Human expansion has apparently occurred in waves; settlement of the Papua New

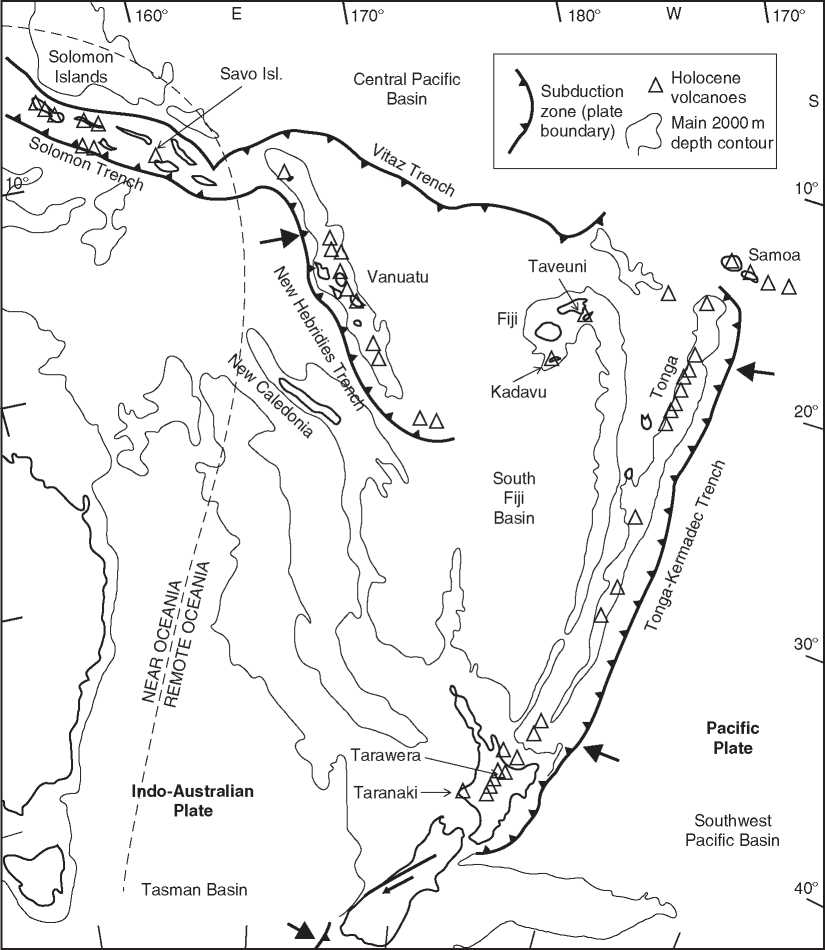

Figure 1 Map of the volcanic portion of the southwest Pacific including the major tectonic and structural geology elements of the area, including many of the sites discussed in the text. The boundary of ‘near' versus ‘remote' Oceania is shown by the dashed line.

Guinea area probably commenced from c. 40 000 years ago, and Papuans expanded relatively slowly into the Solomon Islands. Between 3500-3300 years BP a sudden explosion of human occupation occurred, with the mainstream theories indicating a new group of Austronesian people fanning out into ‘remote-Oceania’ (Figure 1), including Fiji, Vanuatu, Tonga, and Samoa. They brought with them a distinctive type of pottery known as Lapita (Figure 2). The origins of these people have not been confirmed; and there is also debate as to whether they were a ‘people’. However, the main school of thought proposes that people carrying the Lapita technology

Traveled from the Bismarck-Solomons area out into the broader Pacific. Recent DNA work on the Pacific rat associated with the incoming population imply that they may have been new arrivals from southeast Asia. These pioneers had an intensive agricultural practice, bringing with them domesticated plants and animals to form the founding settlements in many areas. After a consolidation period of up to 1000 years, a Polynesian people or culture began to spread to remaining areas of the Pacific, including New Zealand.

A great deal of southwest Pacific archaeological research focuses on the development and variation of

Figure 2 Lapita pottery, a rare large and mostly intact piece found within slope-wash or colluvial sediment containing a large component of volcanic material at the Teouma site, Efate Island, Vanuatu. This lapita burial site is subject of ongoing studies by Dr. Stuart Bedford and Professor Mathew Spriggs, Australian National University and the Vanuatu Cultural Centre.

Ceramic traditions over time and throughout different areas. In addition to Lapita (with characteristic dentate stamped patterns, which is also associated with plainware), paddle-impressed, incised as well as applied-relief ware has been recognized. Relationships between these ceramic traditions within and between geographically different areas have been difficult to establish and recent work suggests that while the Lapita tradition may have been initially homogenous, stylistic variations on this probably followed independent courses in different areas.

Settlement of the greater southwest Pacific, despite being initially rapid, was not without its challenges for the new arrivals. The area is vast; over 30 million km2 and primarily this is open ocean, dotted by almost insignificant areas of land. The estimated 25 000 islands in the southwest Pacific make up only <0.5% of the area. Even if the ‘large’ landmasses of Papua New Guinea and New Zealand are considered, land coverage is still <3% of the ocean area. This isolation and the harsh traveling conditions appeared to be of little hindrance to the expansion of the human arrivals since they had a high level of seafaring technology. However, the overall lack of land meant that any suitable habitation site was attempted, and often persisted with, even in the face of potential volcanic hazard.

In the first instance, many of the existing low atolls and coral islands were submerged in the mid-Holocene (c. 6000-5000 years ago), only rising above the waves as the sea level dropped by 2-2.6 m over the next few thousand years. Hence, biodiversity on these islands was poor, along with difficult water Supply, lower soil fertility, and a greater isolation relative to the volcanic islands. By contrast, volcanic islands were particularly fertile, with good water supplies, although there may have been an issue of malaria present in inland mountainous areas. The overall comforts of the volcanic islands may have been a reason for an apparent later settlement of more easterly lying coral islands compared to the western, mainly volcanic, islands.

The main volcanic areas of the southwest Pacific are located along part of the so-called ‘ring-of-fire’, which marks the location of plate-subduction systems along the edges of the Pacific Basin (Figure 1). This includes areas of high concentrations of active volcanoes in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Tonga, and New Zealand (see Oceania: New Zealand). Many individual volcanoes formed mountain or caldera (large collapsed crater) structures, with a volcano or overlapping volcanoes comprising the entire island. In addition, a larger number of submarine volcanoes dot the seafloor along this volcano line, some of which also appeared and disappeared above and below the waves over time. In all of these areas, many eruptions have occurred in the last 200 years of recorded history. In addition to the plate boundary volcanism, so-called ‘intraplate’ volcanoes occur in parts of the Pacific, particularly Samoa, and parts of Fiji (e. g., Taveuni), as well as older and smaller tectonic features that may be currently inactive but still capable of causing volcanism (e. g., Kadavu, Fiji). Many of these areas also have either historical volcanic activity or at least evidence of eruptions in the last few hundred years.

World History

World History