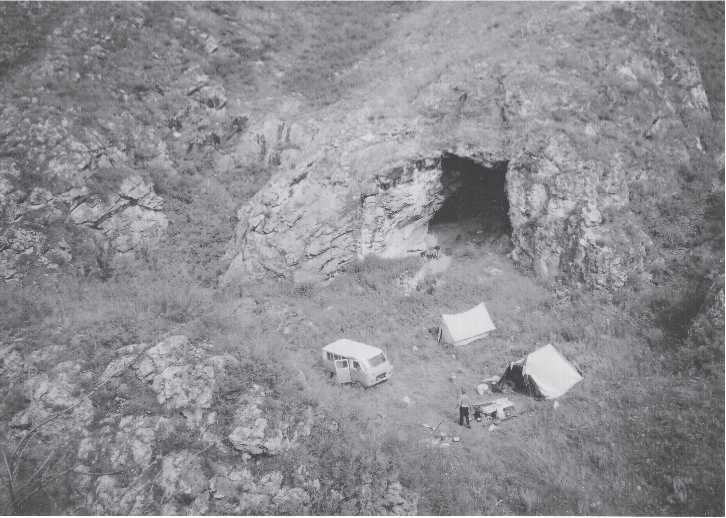

Dvuglaska Cave (Two Eyes) was brought to the attention of archaeologists by Krasnoyarsk speleologists in 1962. It is located in southern Siberia’s Khakasian Autonomous Republic, about 400 km north of its border with the vast, high and arid Mongolian steppe country. The main city of Khakasia, Abakan, through which flows the Yenisei River, is south-southeast 46 km from Dvuglaska. This cave is located at 54°080 N and 91°040 E. It faces southward from the floor of a short steep-walled twisting box canyon about 5 km from a poor, dirt-streeted, two-water-well village named Tolcheya, which is dependent on a run-down remote dairy enterprise. A large, clear and permanent stream about 0.5 km from Dvuglaska Cave comes out of the nearby foothills, flowing to and through the village, eventually contributing to the Yenisei River. Situated at the relatively low elevation of600 m, the regional steppe climate is considered as mild. Snow cover has usually melted by the end of March, and there is only about one half-month of frozen ground. The interior cave temperature in mid-July was 15°C (59°F) at 10:00 a. m., and17°C (63°F) at 5:30p. m.

Dvuglaska Cave is situated at the lower boundary of the craggy limestone Batenev foothills that look out over the vast treeless Bogradsky steppe plain, set in the center of the Minusinsk Depression (Figs. 3.16-3.23). The foothills have thin stands of tall old conifer trees mixed with sage, short-grasses, and low flowering plants. The bowl-shaped cave is about 10 m wide, 15 m deep, and from the present-day cave floor, about 4 m high. It is well-formed for protection against the heaviest summer rain storms and winter blizzards. However, being situated in a box canyon without a direct view of the steppe plain, it would have been a risky place for humans to live on a long-term basis. There would have been no natural protection from either predatory humans or large carnivores chancing into the box canyon fTom the steppe. Today, the cave’s occupants are a few silent rodents, a small coming-and-going flock of pleasant-cooing rock-pigeons, and rare visits from nearby villagers partying around evening campfires.

At the mouth of the cave there is about 3 m of rocky fill, while at its rear there is almost no trash or roof spall. Judging from the very large number of sharply angular cobble - and pebble-sized rocks in the cave fill, there has been a slow and steady rain of rock from the highly fractured roof. The cave’s name derives fTom two circular sky-lit holes in its roof that look like shining feline eyes in the darkened grotto - hence “Two-Eyes” cave.

Fig. 3.16 Dvuglaska Cave. Z. A. Abramova and associates carried out the initial excavations of this cave in 1974. In various publications she referred to it as a “Mousterian Grotto” and a “Neandertal dwelling.” Our brief re-testing, aimed at primarily securing charcoal for new carbon-14 dating, produced almost no cultural material but plenty of hyena and other large-carnivore-damaged bone. The cave is situated in a short box canyon whose entrance is out of sight to the left. (CGT color Dvuglaska 7-18-00:2).

In 1974, 1975, 1978, and 1979 excavations in Dvuglaska Cave were directed by St. Petersburg’s Z. A. Abramova (Abramova 1980, 1981, 1985, Abramova et al. 1975, 1991, Abramova and Ermolova 1976, Vasili’ev 2000). Abramova, Ermolova, Eritsan, and Ovodov tested the floor of the box canyon immediately outside the cave and its opening earlier, in 1971-1973. In 1975 the cave and excavation were examined in detail by geologists M. Muratov and V. A. Panychev, archaeologist Yu. V. Grichan, and vertebrate paleontologist N. D. Ovodov. By the end of 1979 an area of 38 m3 at the cave entrance had been excavated through the loose rocky sediments to the basal bedrock at 3.8 m depth. This multi-year expedition recovered bones and teeth of extinct Pleistocene animals and a few stone artifacts. The types of artifacts led these workers to view the occupants to have been Mousterians, the term used in publications about the cave’s excavation (Abramova et al. 1975, Abramova and Ermolova 1976, Abramova 1981, 1985). Other publications that focus on or include Dvuglaska Cave are: Abramova et al. (1991); Vasili’ev (2000); and Ovodov and Martynovich (1992).

Abramova and the geologists identified eight stratigraphic levels at the entrance to Dvuglaska Cave. The oldest bone and artifact-bearing levels were 5-7 (Level 8 was sterile). Levels 5 and 6 had faunal remains of species that suggested a relatively warm and

Fig. 3.17 Dvuglaska camp. A few pieces of lumber borrowed from a nearby village served for a low dining table and benches. Left to right: driver, Nicolai Ovodov, Olga Pavlova, Lena Popkova (behind Pavlova), and Nicolai Martynovich (CGT neg. Dvuglaska 7-20-00:36A).

Fig. 3.18 Dvuglaska artifacts. A 5.1 cm long, eyed, sewing needle and a sliver of polished bone were found

In the 20 000 BP upper level of the cave deposit. These were the only artifacts we found, and well above the lower levels thought by Abramova to be Mousterian (CGT color Dvuglaska 7-20-00:26).

Fig. 3.19 Dvuglaska bone and tooth fragments. Coarse-screened faunal remains. Much of this

Breakage appeared to have been perimortem. Pocket knife in lower right is ca. 10.0 cm long (CGT neg. Dvuglaska 7-20-00:36).

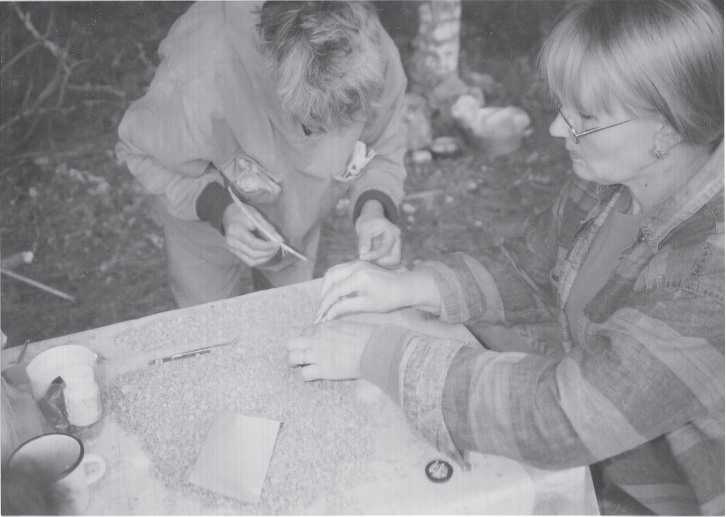

Fig. 3.20 Final sorting. Nicolai Martynovich (left), bird paleontologist, and Irina Foronova, mammoth

Specialist, do the final sorting of tiny teeth and bones of Dvuglaska rodents, bats, and birds. None of these pieces met our size selection criterion (>2.5 cm) for this perimortem taphonomic study. Nevertheless, an informal search for perimortem damage turned up nothing (CGT color Kurtak 7-23-00:30).

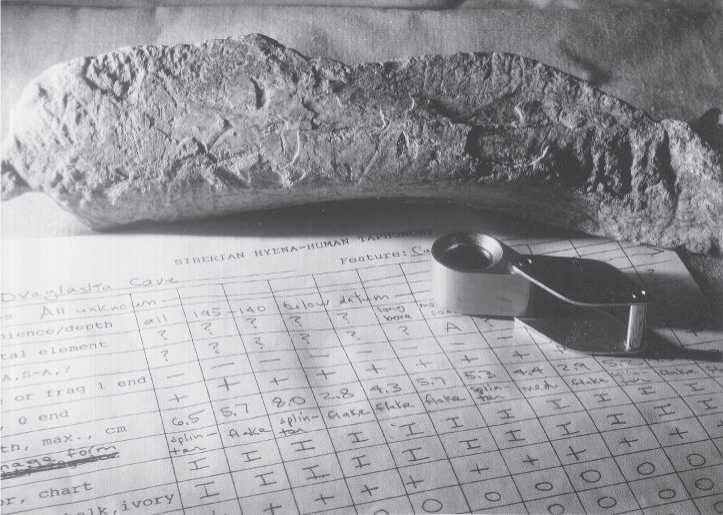

Fig. 3.21 Large Dvuglaska bone fragment. Most of the perimortem damage found in the Dvuglaska bone assemblage is attributable to hyenas and other large carnivores. For example, this bison radius, 25.5 cm in length, shows chewing scratches and dints, and end-hollowing, but no signs of human damage. Found at 140-195 cm depth (CGT neg. IAE 8-15-00:16).

Dry climate. Ermolova (in Abramova et al. 1975) identified bones of Onager (Equus hemionus) and horse (Equus cf. caballus) as being the most frequent species. She also identified rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), bison (Bison pricus), wild sheep (Ovis ammon), red deer (Cervus elaphus), saiga (Saiga tatarica), cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea), cave lion (Panthera spelaea), bear (Ursus sp.), gray wolf (Canis lupus), fox (Vulpes vulpes), glutton [wolverine] (Gulo gulo L.), and pika (Ochotona sp.). Remains of mammut and caribou were very rare.

Despite Dvuglaska Cave providing a relatively comfortable camp site, especially in the summer, the evidence for human use is limited. Abramova identified artifacts mainly from Level 4. These included two cores, two point fragments, a retouched blade, two scrapers, three screblos, and a modified piece of antler. Levels 5 and 6 yielded a few Levallois points, large disc-shaped cores, and some very large flakes (Abramova et al. 1991). On typological grounds these were viewed as being culturally Mousterian. Relative to the abundant evidence of Middle and early Upper Paleolithic occupation in the Altai, it would appear that the Minusinsk Depression during those time periods had very little human presence.

While our testing produced no stone artifacts, those that Abramova and associates found were later examined in 1986 by John Hoffecker (personal communication, April 19, 2003). He felt that they were Levallois flakes and points. He expressed surprise that

Fig. 3.22 Dvuglaska pseudo-cuts. Five marks that look very much like cut marks, but each one has a

Rounded surface edge rather than a sharp border. The longest of these is <0.6 cm. Actual width of image is 3.3 cm (CGT neg. IAE 8-15-00:30).

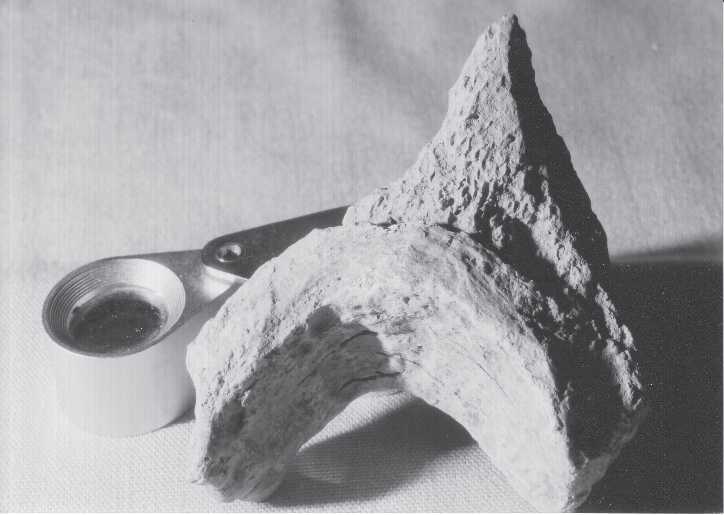

Fig. 3.23 Dvuglaska stomach bone. This piece of pelvic acetabulum has a maximum diameter of 7.2 cm, making it one of the largest ingested pieces seen during this project (CGT neg. IAE 8-15-00:27).

Neanderthals were living so far north and east, possibly because conditions were much warmer than today.

The present authors, assisted by Nicolai Martynovich, Elana Popkova, and a hired driver and his personal four-wheel-drive microbus, visited, set up camp, and carried out a small-scale broadside excavation on July 17-21, 2000. This work was proposed to, and approved by, IAE director, Academician Derevianko. The objectives were to: (1) enlarge the faunal sample for our taphonomy project; (2) re-collect charcoal samples for renewed dating of the cave’s human occupation; and (3) for the senior author to see how paleontological excavation was done in Siberia and what sort of tools were used that might accidentally leave false cut and chop marks. Our work was a two-step procedure. First, we cleared away the rocky debris that had slid down over the front face of the cave deposit for some 25 years. This provided a ITesh vertical face to the cave fill at its opening. The fresh face extended from the present cave floor surface with its modern trash of cans, bottles, and remnants of camp fires, to a vertical depth of about 3.0 m. The width of the broadside was about 2 m. Second, we excavated the fresh face inwards to a horizontal distance of about 25 cm, producing a volume of some 1.5 m3. We recovered several thousand pieces of small rodent, bird, and bat bones and teeth, along with bones and teeth of bison, horse, rhinoceros, sheep-goat, and pieces of other large but unidentifiable mammals. We screened the entire excavated sample three times, first with half-inch hardware cloth, then with one-sixteenth-inch mesh all the material that had passed through the first screen. The second screening was then water-washed and dried to later extract the tiny bones and teeth of rodents, birds, and bats. All the larger bones were either recognized in actual excavation or caught in the first screening.

The two carbon-14 dates that we obtained from the upper and lower charcoal samples are 17 000 BP and 29 000 BP, respectively. Our dates may have little to do with the human use of Dvuglaska, inasmuch as the charcoal lenses seemed not to be hearths or even the scattered ashes of camp fires. The charcoal flecks could well have been blown into the cave from a nearby lightning-caused summer wildfire. However, the dates do give a good basis for assuming that the cave was available to humans and non-human animals alike for at least 30 000 years. Vasili’ev et al. (2002:521) list one carbon-14 date based on bone for Dvuglaska - namely 27 200 BP. Near the upper charcoal layer, a small-eyed bone tailoring needle was found. If the charcoal and needle are in true stratigraphic association, then the needle is one of the earliest known in Siberia. We also found a polished bone splinter, much like a toothpick. It is quite evident the cave was only rarely used by humans. Its main large occupants were hyenas, whose chewing damage is abundantly evident in our faunal sample, as are the numerous stomach bones.

World History

World History