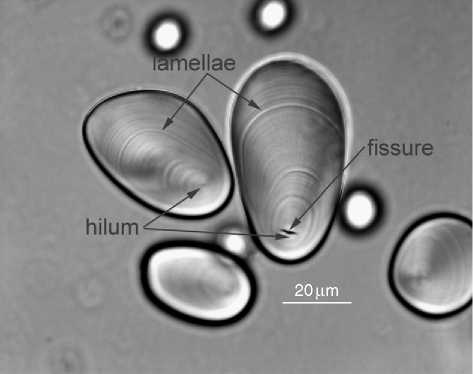

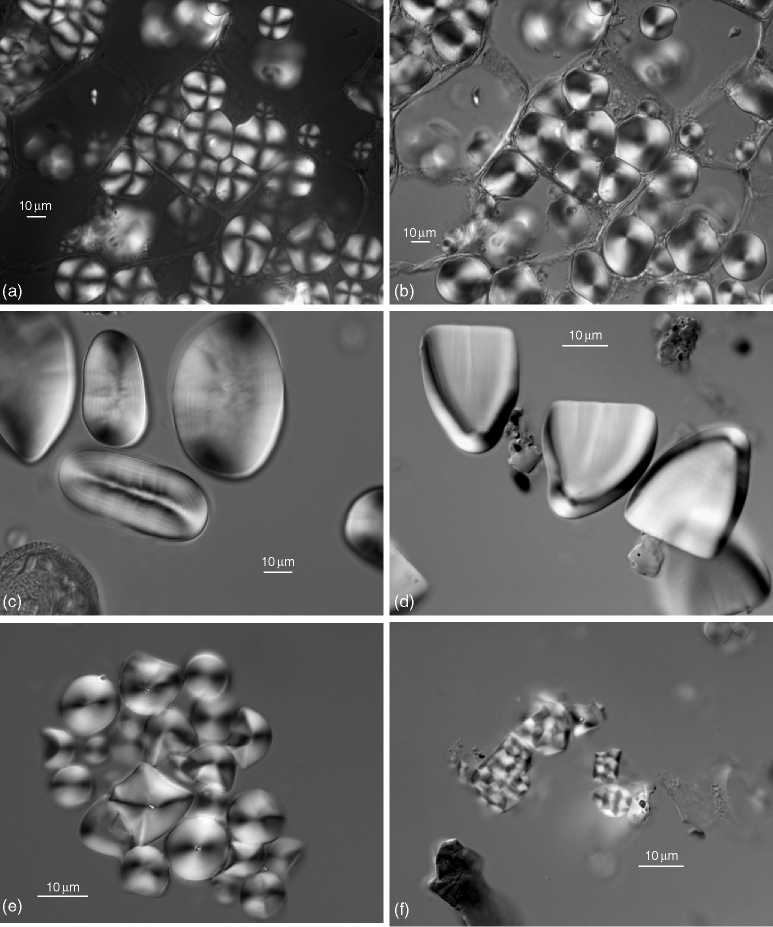

Starch is a polysaccharide; specifically, a polymer of a-D-glucose. Starch is formed in chloroplasts in the green parts of plants, and in the amyloplasts of plant storage organs such as tubers, seeds, and sporocarps. Starch granules in chloroplasts are termed transient starch, are very small, and often have no distinguishing features. The starch granules formed in amyloplasts do not contain chlorophyll, are much larger than those produced in chloroplasts, and exhibit a range of morphologies. The size and shape of starch granules is governed by plant genetics and environment. There are two chemically distinguishable entities in starch: amylose (linear polymers) and amylopectin (highly branched polymers). Starch grains grow from a central point called the hilum with the accretion of layers of amylose and amylopectin (Figure 1). In transmitted, polarized light, starch granules exhibit a birefringent effect seen as an extinction cross (Figures 2a and 2b). If the angle of polarizing filters is changed, the extinction

Figure 1 Plan view of a starch grain from Solanum tuberosum (potato) showing the hilum and lamellae (concentric lines) typical of starch. A fissure is present at the hilum of one of the starch grains. Photographed using a transmitted bright field microscope. Photograph: Judith Field.

Figure 2 (a) Starch granules under cross polars in a section of kernel from the black walnut, Endiandra palmerstonii. (b) The same section as (a), but viewed with differential interference contrast microscopy, (c) Plan (upper granules) and profile (lower granule) views of starch granules from the fern Marsilea drummondii, commonly referred to as nardoo, under differential interference contrast microscopy. Note the irregular margins, the folding of the surface, the faint lamellae, and the flattened area around the hilum. The apparent pinched ridge down the center of the grain shown in profile produces a different extinction cross to that seen when viewed in plan. Starch preparations shown in (a), (b), (c), (e), and (f) are mounted in Karo syrup, and (d) is mounted in Euparal (d) Plan views of starch granules from the tuber of Dioscorea bulbifera (hairy yam). Note the eccentric hilum (arrow) and the differences in shape and hilum position between this and the other starch granules. (e) Starch granules of the aquatic taxa Triglochin sp. (water ribbons). (f) Starch granules (compound form) of the grass Eragrostis eriopoda (woolybutt). Note the very small size of individual grains. Photographs: Judith Field.

Cross follows the rotation of the filters, with the cross axis around the hilum. This feature allows the easy identification of starch in residue extractions.

The investigation of archaeological indicators of starchy plant food use primarily involves the evaluation and documentation of the morphology of starch from different plants and plant organs, rather than the study of starch residue biochemistry. The analysis of

Starch grain morphology is particularly useful as conclusive results can be obtained from the typically small quantities of starch recovered from archaeological sediments and artifacts (e. g., for soil: 50 granules/ 10 gram of sediment). Importantly, the questions most commonly asked of starch residue analysis relate to identifying specific and/or multifunctional plant use, and the identification of the plants being processed.

World History

World History