Archaeological deposits often have more complicated site-formation histories than natural ones because they encompass a potentially infinite variety of anthropogenic activities (see Figure 1). Thus, at a tell or mound site, for example, we might observe combinations of interdigitated features and constructions (e. g., walls, plazas, and kilns); domestic occupation, including combustion zones and pene-contemporane-ous rake-out of ashes charcoal (see Figures 2 and 3), and bone; and agricultural practices adjacent to the site (e. g., plowing, manuring). Moreover, people can rework and modify archaeologically contemporaneous features and deposits, as in the case of pits (see Figures 4 and 5), fills, and dumps. Furthermore, all of these types of activities can often take place on the same existing substrate, thus making it difficult to isolate individual strata and associated events. Anthropogenic deposition and alteration become particularly noticeable from the Middle Palaeolithic onwards (after c. 250 ka), ultimately encompassing most Holocene sites in the Old World, and particularly Late Holocene mound sites in the New World.

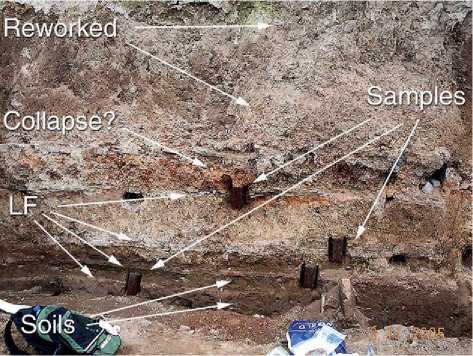

Figure 1 Field photo of an archaeological profile at Huizui, loess plateau, Henan Province, China; Yangshao (Neolithic c. 50003000 BC) construction of lime floors (LFs) over buried alluvium or possible paddysols (soils); also visible are burned daub (Collapse), the upper homogenized (Reworked) levels, and plastic downpiping monoliths (Samples) for soil micromorphological investigations. Collaboration with LaTrobe University, Australia and Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing.

World History

World History