This chapter is a reflection rooted in our own experience, so of necessity it takes the form of a personal narrative about our struggle to identify unexamined assumptions that we set out to address in our latest fieldwork-based project in Honduras. The issues we raise revolve around how to come to terms with the reality of persistent habitation of places by indigenous people through the period of initial colonization into at least the nineteenth century, in an archaeological discourse that insists on dividing everything into pre-Hispanic and ‘historical’ facets.

We found at every turn that this slippery terrain—which Rosemary Joyce, as an archaeologist trained to discover, explore, and interpret only pre-Hispanic sites experienced as embodied practice—confronted us with vexing contradictions. How can we cope with the fact that the first European records of this area, in the letters of Hernan Cortes, drew on maps provided by indigenous people in Mexico? Is this part of the reason why the opposite of historical in the former colonies of Spain is pre-Hispanic, not prehistoric? And does this same opposition not imply that the historical period is Hispanic? What do we make of the indigenous actors whose ancestors survived the demographic disaster of the sixteenth century and whose legacy exists in the modern population of Honduras, not to mention the African-descendant peoples, only some of whom have visibility today as recognized parts of Honduran society? Changing our terminology for the second half of the dichotomy—we could distinguish the historic period from a pre-Columbian period with some justification, since Honduras is the location of Columbus’s first contact with Central America, on his fourth voyage in 1502—does not really make things better. While this intervention included the forcible seizure of a canoe plying the coast and may well have introduced

Previously unknown diseases, it did not initiate any remarkable transformation in social life that archaeologists or historians can witness. If we truly believe a distinction can be made between historic and pre-Hispanic, pre-Columbian, or prehistoric, when do we choose as the year that ‘history’ began—in Honduras, for example, 1502 (Columbus’s landfall there), 1524 (Cortes’s formation of sanctioned colonies), 1536 (the division of indigenous communities in service to Spanish soldiers by Pedro de Alvarado), or some other date of institutional inauguration or cultural dominance?

The most immediate outcome of our grappling with these and related questions was a decision to characterize our work as being about ‘the archaeology of colonial Honduras’, thus avoiding the unintended implication that there was a privileged period when Hondurans lived in history that coincided with some event related to European colonization. Yet this change in terminology does not solve any of the problems listed above. We are still left to confront how we imagine the different experiences of place and time by people with deep roots in the area and others who first established themselves in the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, or nineteenth centuries who would manifest themselves in the material registers we have available through archival research and excavation. We are no closer to solving the dilemma of history and prehistory by side-stepping these paired terms. We have, in fact, to make our way through engaged practice. What that suggests is that archaeology finds it hard to avoid creating discontinuity so long as it clings to metaphors of identity.

Instead, we now realize we need to talk about histories, unfolding or interrupted, punctuated by events that we need to address at a variety of scales from the personal to the governmental, from the household to the landscape. In a profound way, the colonial histories we believed we were going to explore are always entangled with those that came before, and themselves are not a single history. The messier terrain we now confront begins with anchoring in places and people and is measured not by periods (the medium of pre-Hispanic archaeology) or centuries (the alternative language of the historical archaeology of Central America) but by lifetimes and historical memories (see also Aguilar and Preucel, this volume).

8.1 PLACES IN HISTORY

There is no difficulty defining the overarching goals of our project, however contentious we have found delimiting its temporal scope and deconstructing the implications of that act of temporal definition. We are examining how different institutions of Spanish colonization, starting in the sixteenth century, provided opportunities for the tactics of persistence taken up by indigenous communities with deep roots in Caribbean coastal Honduras through to the nineteenth century (Sheptak et al. 2011). In the transition following independence from Spain in the nineteenth century, people in communities in the lower Ulua River Valley were reclassified by republican governments. No longer identified as pueblos de indios (towns/populations of Indians), these governmental actions broke the chain of continuity in indigenous identity in ways familiar to historians of this transition in Central America (Dym

2006) . The same processes, not coincidentally, also erased much of the evidence of long-standing participation by African-descendant populations in colonial Honduran society.

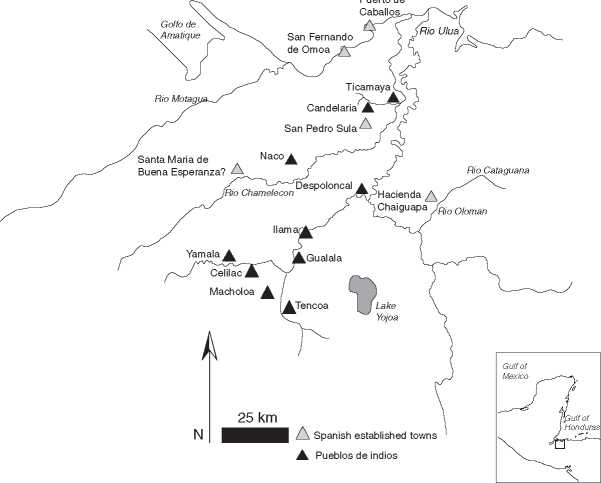

Our project builds on a dissertation (Blaisdell-Sloan 2006) that documented life from the thirteenth century ad through the nineteenth century at archaeological site CR-337, located near the modern city of San Pedro Sula, Honduras (Fig. 8.1). Parallel documentary research demonstrated the likely identity of CR-337 with the historically documented town Ticamaya, originally the seat of a leader of indigenous resistance to Spanish invasion of what the documentary record calls the ‘provincia de rio Ulua’ (‘province of the Ulua River’; Sheptak 2004,

2007) . The juxtaposition of archival documents and excavated materials shed light on social life in the colonial pueblo de indios of Ticamaya, tributary directly to the Spanish Crown in the early colonial period and providing service to the town and military garrison of the Fortaleza de San Fernando de Omoa in the eighteenth century.

Our intention is to compare the history of Ticamaya as a colonial place to that of another indigenous town located further inland, Despoloncal, where brief archaeological testing documented contact-period remains (Wonderley 1984). Documentary research demonstrates a long history of persistence as a pueblo de indios owing service to a series of Spanish encomenderos (holders of labour rights), initially living in the nearby city of San Pedro and later absent in the colonial capital of Santiago de Guatemala, at least through to 1742.

To complement the comparison of experiences in these pueblos de indios, we also projected working in places newly established to address Spanish colonial interests. One of these would be the suspected archaeological location of historically documented Hacienda Chaiguapa, recorded in a survey project (Joyce and Hendon 2000) as PACO 12. Twenty structures formed three clusters along the Quebrada Chaiguapa. At one edge of this linear distribution of structures was a single large building,

Caribbean

Fig. 8.1. Map showing locations in northern Honduras discussed in the text

Approximately 15 x 15 m and 2 m tall. This larger building stood out as unique among over 500 structures mapped, the only large structure that was approximately square in footprint. It was adjacent to a second square structure, measuring approximately 10 x 10 m and 1.5 m in height. The majority of the structures at PACO 12 are smaller—less than 75 cm tall, 4-11 m long, and 3-8 m wide—and fall entirely within the norms for the wider valley survey, overlapping with the pre-Hispanic residential structures we excavated (Fung 1995a, 1995b).

At the time of our original investigations, we did not consider the possibility of a colonial date for these buildings, something we now think is quite possible. In 1776, a contingent of indios was assigned to work under a revived system of repartimiento, or tributary labour, on Hacienda Chaiguapa (AGCA Signatura A3.12, leg. 186, exp. 1889). Among them were residents of the town of San Juan de Jocon, in the administrative district of Yoro, who petitioned in the same year for relief from service on the Hacienda Chaiguapa (AGCA Signatura A3.12, leg. 509, exp. 5299). They argued that the hacienda (a general term used for ranches and rural plantations), belonging at that time to Don Jose Marin, was over five days distant, and that Jocon itself had too few tributaries to fulfil its obligations in taxation without the labour of all. Specifically, the town was said to have only eighteen tributaries, with other resident indios described as forasteros: people living outside their community of birth, and so subject to tribute in their birth community, not to contribute to the tribute of Jocon. Hacienda Chaiguapa would have been typical of new cattle ranches established in the late eighteenth century, and we now suspect that the site we documented, which yielded no diagnostic pre-Columbian pottery, might represent this distinctive colonial place.

For pragmatic reasons, our first two seasons of exploratory excavations and community outreach in 2008 and 2009 took place at another site of Spanish colonial labour relations from the eighteenth century, the fortress of San Fernando de Omoa and the town that developed around it (Gomez et al. 2010; Joyce et al. 2008). Here, the Instituto Hondureno de Antropologia e Historia was planning to build a new museum, and the Instituto Hondureno de Turismo (IHT) was carrying out refurbishment and architectural interventions intended to stabilize the fort against perceived dangers of collapse and make it more attractive for international tourism.

The first season saw us conduct stratigraphic tests in the fortress itself to assess the archaeological potential of deposits, when it was discovered that the proposed work of the IHT included digging out all the largely intact floors inside the rooms of the seaward side of the fort. Based on this work, we established an architectural chronology integrating the known historical dates of development of the first and second forts beginning around 1750 and extending to the 1780s (Hasemann 1986). Artefacts associated with the excavated features, however, extended the period of active remodelling of the fort quite a bit later than this initial colonial period, showing marked construction events dating no earlier than the 1840s. We also recovered chipped obsidian points and hand-built, low-fired earthenware ceramics in the same deposits yielding European ceramics. Since the contexts of all of the datable material in the fort were architectural fills, we were left uncertain whether these came from an indigenous village predating the fort or from labourers working on its construction or living there as tribute labourers once it was in service.

Our second season at Omoa was the first step in a planned investigation of remains of houses in the town, where historical documents show a population of enslaved Africans, free blacks, and free African-descendant people of varying levels of wealth and social status lived, along with small numbers of Spanish residents explicitly identified in census documents as white (blanco) and indigenous workers from the nearby towns of Ticamaya and Candelaria who rotated in service owed to the fort (Caceres 2003; Sheptak 2008a, 2008b). We were able to identify traces of an indigenous household that occupied the area immediately before the construction of a row of brick-floored, tile-roofed houses with brick wall foundations, whose latest residents consumed products dating between 1780 and 1800. In one area, we recovered material from the brief period between 1910 and 1930, when the Cuyamel Fruit Company and its successor, the United Fruit Company, occupied the site, building the structure today occupied by the small on-site museum.

When we talk this way—about the stratigraphic sequences of features and their likely calendar ages—the problems of chronological reference disappear. Where Joyce in particular had difficulty was in identifying what kind of archaeology this was. Historical archaeology? (Does this imply we should ignore the possibility of pre-Hispanic components here, at a place where Spanish documents recorded a pueblo de indios in 1536, abandoned by 1582?) Colonial archaeology? (If so, should we ignore the mid nineteenth - and early twentieth-century deposits?)

This question of terminology seemed especially fraught as it reflected immediately on the kind of archaeology Joyce has previously done; it forced her to confront the fact that, without noticing it, for decades she helped maintain a false distinction between prehistory and history in Honduras. So, this chapter centrally concerns how one might think about this kind of positioning. What might differences in thinking about such positions—being or not being an historical archaeologist, doing or not doing colonial, republican, or pre-Hispanic archaeology— make in the practice of site identification, selection, testing, and interpretation?

8.2 OF HISTORIC CHURCHES AND PREHISTORIC HOUSES

We thought that our adoption of ‘colonial and republican’ in lieu of historical to label the archaeology we are now doing was a unique way to avoid the difficulties we discussed above, until we ran across precisely this same language in the published work of Joel Palka on his project on Lacandon Maya sites in Mexico and Guatemala (Palka 2005; see also Palka 2009: 300-2). Our mutual avoidance of the term ‘historical archaeology’ may well stem from the same roots, even though our projects are vastly different: Palka dealt with the ethnogenesis of the Lacandon as an independent people deliberately maintaining a distance from Spanish and later Mexican settlements, while also participating actively in the global commercial economy brought into their reach by Spanish and British colonies.

What unites our projects and makes the term historical archaeology not just inappropriate but unthinkable is the implication that the contrasting term, ‘prehistoric archaeology’, should be applied to the preceding indigenous societies of Mexico and Central America. That just does not work. There are societies in the region that used script to record events and dates. Even in the area of northern Honduras where we work, where historical texts of pre-Hispanic date are unattested, our assumption is that there was a form of historical consciousness rooted by calendrical recording of events. The peoples of Honduras in the sixteenth century employed versions of the complex calendars whose recording was a principal impetus to textuality in the region. Their predecessors in the first millennium ad painted individual signs identifiable with signs in the widespread Maya script on pottery, which, unlike bark paper or deerskin, survived to suggest some form of literacy. Most important, indigenous people in Honduras in the twentieth century offered oral accounts of creation and the succession of humans that represent the same kinds of historicity analysed using the few preserved pre-Hispanic books from Mexican territory. Central American societies are not those of ‘people without history’, and neither Palka nor we can subscribe to differentiating post-contact archaeology as uniquely historic.

If this is true, why did it take more than two decades for Joyce to consider conducting archaeological research directed to understanding more recent historical periods? She began fieldwork in Honduras in the late 1970s, with a focus on settlement patterns and a commitment to household archaeology. She conducted settlement surveys in two different areas, the lower Ulua River Valley and the Oloman and Cataguana valleys in the modern state of Yoro, both of which, she now realizes, have a wealth of archival documentation from the sixteenth century on. Nonetheless, she was neither sensitive to the presence of post-Columbian sites, nor particularly interested in them.

In 1983, Rus Sheptak strongly urged that a specific effort be made to identify sixteenth-century sites in places where names recorded in early colonial documents persisted in modern place-name practice. Kevin Pope (1985) and Anthony Wonderley (1984) visited the locations Sheptak identified for sixteenth-century Ticamaya and Despoloncal, in each case recovering ceramics considered diagnostic of Late Postclassic

Honduran settlements, specifically, a red on white painted type called Nolasco Bichrome. Yet Joyce, at that point directing a settlement survey, made no additional effort to survey other locations of this kind to add to the sample of known sixteenth-century sites. In part this was because Despoloncal and Ticamaya were sites with no surface-visible architecture, making them incomparable in a settlement analysis organized around mapping of building remains. In a related argument, Palka (2009: 300) has attributed the delay in development of historical archaeology in Mexico and Central America to problems of visibility.

Another part of Joyce’s uninterest in pursuing this agenda in the 1980s almost certainly can be attributed to the lack of discernible features in the test excavations Wonderley carried out that might have allowed interpretation of household life at these places. For an archaeologist concerned about introducing household archaeology as a new mode of understanding action by individuals and factions to replace regional ethnic frameworks received from cultural history, all these sites seemed to promise was more typology.

Joyce’s uninterest—and Sheptak’s persistence—continued as she proceeded to carry out a survey in Yoro (Joyce and Hendon 2000). When the survey was planned and carried out in the early 1990s, we engaged in a sharp and at times contentious debate about how to recognize historic sites, fuelled by our different ways of thinking about these landscapes. Joyce perpetuated the received practice ofsettlement pattern archaeology in the country, which not only failed to engage with sixteenth-century sites, but in fact emphasized the period from about 500 to 1000 ad represented by the majority of surface-visible site remains. Sheptak approached the same landscape from his detailed knowledge of Spanish colonial documents.

Having conducted the stereo air photo survey for the project, Sheptak encouraged Joyce to attend to possible evidence of colonial sites. Even with the limited amount of detailed historical work in Honduras at the time, there was already a clear colonial documentary record for the valleys of Oloman and Cataguana, the focus of this new project (Davidson 1985). As we have discussed above, we now believe that one of the sites identified through survey in this project likely represents the historic Hacienda Chaiguapa.

Sheptak proposed that Joyce be on the alert for ‘melted churches’: the slumped foundations of distinctive adobe buildings that would have formed a part of every pueblo de indios. In context, this was a very productive response. First, it responded to the pragmatic problem Joyce had: Given that indigenous people were not relocated into planned communities of newly constructed houses as an immediate consequence of colonization and experienced no influx of new goods, it has been difficult to identify a material ‘signature’ for colonial occupations. At the same time, the demand and response perpetuated the idea that there is a diagnostic discontinuity that inaugurated the historic period—even if we call that period colonial.

Our dilemma is by no means unique. The only previous archaeological project in Honduras specifically directed at exploring the transformations introduced with European colonization on a regional scale confronted precisely the same challenge. In this effort in the 1980s, John Weeks and Nancy Black undertook a survey of archaeological sites in a portion of the Honduran state of Santa Barbara, southwest of our research area, with a focus on missionization (Weeks 1997; Weeks and Black 1991; Weeks etal. 1987). The reports on their work describe the documentation of a series of colonial churches in towns that still bear the names recorded in abundant documentation by Mercedarian missionaries: Tencoa, Celilac, Chuchepeque, Gualala, Ilama, Jalapa, Macho-loa, Ojuera, and Yamala. Yet as Palka (2009: 325) notes, their results ‘point out the difficulties in establishing a chronology based on native material culture. Indigenous pottery and architecture (residential types and possibly adobe) continued in historic times, along with indigenous settlement patterns.’

Historical documents that we are recording in our project show that the towns with churches identified by Weeks and Black persisted as being identified pueblos de indios well into the nineteenth century. Indeed, a land title from Yamala that we are analysing, produced in 1892 long after the indigenous community had been disrupted by epidemics and dislocation during post-independence wars, incorporates eighteenth-century documents referencing indigenous cofradias (sodalities organized around the veneration of a saint) and guancasco, a Lenca practice where the images of patron saints from two communities are carried on visits to the paired town.

So churches are not unambiguous signs of historical discontinuity. Churches, cofradias, and guancasco all figure prominently in eighteenth-century petitions through which the residents of these communities sought to control their lives. The physical structures that housed these Catholic practices are, we have argued, better viewed as sites tactically occupied by indigenous actors, drawing on Michel de Certeau’s (1984) concept of everyday practices as ‘tactics’:

Tactics are not extraordinary, but ordinary; they are the continuing ways

That human subjects occupy social landscapes that they do not entirely

Control. Tactics can be conceived of as the ‘appropriation’ of what is offered

In places like the colonial settings we examine, exceeding the intentions of

Those who seek control, seizing the moment for one’s pragmatic ends.

(Sheptak et al. 2011: 149-50)

While churches may unambiguously date after 1502 (when Columbus was the first European to hold Mass on Honduran soil), they fail as signs of a clear break between pre-Hispanic and historic identities on which archaeological practice could be securely founded. Churches neither transform the communities in which they were built so radically as to mark a transition into history and out of prehistory, nor do they signify the abandonment of previous identities with the assumption of new practices. Churches, instead, stand as excellent examples of hybridity, practices that defy disentangling of continuing and intertwined histories by a population that is best understood as undergoing ethnogenesis.

So, too, in a distinct way, do houses defy easy division into prehistoric and historic. Like Joyce at Hacienda Chaiguapa in Yoro, Weeks and Black in Santa Barbara did not perceive residential structures in their survey as pertaining to the colonial period. Instead, they noted that clusters of late prehistoric or Late Postclassic structures were found ‘in the vicinity of mission settlements’ (e. g., Weeks and Black 1991: 253-4). The impression is left that these structures were from an earlier time, and that mission settlements—which, it turns out, are only recognizable by the presence of churches, the only locations with European tradition goods—were built nearby almost without relation to them. Yet, that is clearly not what these authors intend to convey. Instead, we press here against the categorization of time that is dependent on sharp dichotomous breaks. At times, the demand for us as archaeologists to differentiate historic and prehistoric leads to especially clear evidence that what is actually happening is an exclusive association of history with the (European) documentary record (compare Hantman, Waltz, this volume).

8.3 HISTORY AND DOCUMENTS

The passages about late prehistoric and Late Postclassic structures ‘in the vicinity of mission settlements’ in Santa Barbara are immediately followed by extensive discussions of archival documents concerning Spanish conflict with the inhabitants of Yamala in the late 1530s (Weeks and Black 1991: 254-5). These archival sources are called ‘historical documents’. But when it comes to describing the physical remains that the authors identify as likely the site of events described in these documents, temporality becomes very confusing. What should, for consistency, be called ‘historical buildings’ are discursively represented as something very different—described using other temporal categories such as Late Postclassic.

A quote from a Spanish account of the burning of ‘four houses built very large, and four larger ones full of corn’ is followed by the report of modern archaeological survey identifying, on the basis of location on a defensible ridge top like that described in the Spanish archival sources, the possible remains of what are proposed to be these very buildings:

Site 503 is located about 750 meters west of the ruins of the colonial church on an alluvial terrace above the floodplain at Yamala. The site consists of a small multiple-plaza platform group and generally corresponds to the refuge described____Ceramics excavated from the site indicate a predomin

Ant Late Postclassic period occupation. (Weeks and Black 1991: 255)

Nor is this a unique instance in which a place described in historical documents is said to manifest prehistorical remains. Site 628 is a second location identified with another place described by the Spanish as placed under siege in the 1530s. The structures mapped there are described as probably late prehistoric.

This section of the article goes on to talk about ‘the transition from the Protohistoric to Colonial periods’, said to be ‘marked in the archaeological record by several pottery types and the introduction of colonial glazed ceramic inventory as well as by the extinction of many aspects of the pre-Hispanic settlement system’ (Weeks and Black 1991: 255). The introduction of an otherwise undefined ‘Protohistoric’ period seems designed to try to solve the problem of the spatial distribution of European tradition goods (markers of the colonial period) only in churches. Presumably, the Protohistoric category would be used for those settlements that continue aspects of the known indigenous ways of occupying space, where people continued to make and use hand-built earthenware pottery and chipped stone tools, but might have been occupied after the first Spanish encounters represented by the battles described in Spanish archival documents. Coloniality, in this reading, does not begin with Spanish engagement but with specific forms of institutional intervention—specifically, missionization. Yet, the language afforded us to make such a subtle distinction—in effect, defining a chronological period lasting from about 1534, when the Spanish governor of Honduras founded a new town that expected labour from the people of Santa Barbara, to 1554, when the first Mercedarian mission was established in the region—locks us into a logic that views contact with Europeans as inherently transformative, bringing indigenous people into (some form of) history, even if only nascent.

The most recent treatment by Weeks (1997: 94-5) contains a similar profusion of temporal markers for the physical remains that are the sites of events described in archival Spanish documents: ‘sixteenth-century Honduras’, ‘late prehistoric and Early Colonial’, ‘late pre-Hispanic’, and ‘Postclassic and Colonial periods’ follow each other in the space of two paragraphs. Only slightly later, we learn that ‘nine sites of the Historic period were located during survey’, all of them based, apparently, on the presence of the remains of abandoned or still-used colonial churches (Weeks 1997: 95). Detailed discussion of an intensively sampled survey zone, the Yamala area, says it provides evidence of ‘a continuous settlement sequence from the Late Preclassic through the Historic periods’, but an accompanying table shows only one site with ‘Colonial’ occupation, a reoccupied Late Classic location. Five sites with Late Postclassic occupation have no indicated colonial remains. Closer scrutiny reveals that the lone colonial site is the mission church at Yamala. At the same time, historical documents are cited for the ‘early sixteenth century’ Site 504, which the accompanying table indicates was abandoned after the Late Postclassic (Weeks 1997: 97-8).

We cite this pattern of shifting temporal reference not as a criticism of the work accomplished by these pioneering scholars but as evidence of the shared inability of archaeologists in Honduras to solve the problems of temporal reference in a way that allows us to talk about history sensibly. Indeed, it appears that the desire to contrast sharply what was there when Spanish observers arrived and what existed once they were on the scene will inevitably cause contrasting terms to spawn new ones, in a chain that almost always suppresses one half of a dichotomy. So, in Santa Barbara, the presence of Europeans in the region introduces history and leads to terminologies that stress historicization or colonization, yet make it difficult to ‘see’ indigenous houses at all. When instead we try to maintain the visibility of indigenous houses and traditional practices at sites like Despoloncal and Ticamaya, we may find ourselves talking about pre-Hispanic technologies—in the early nineteenth century. Or, as in the case of Joyce’s blindness to the possible identification of the archaeological remains on the modern Hacienda Chaiguapa with the eighteenth-century hacienda recorded in documents, we may be unable to even conceive of the more recent history as a possibility because there is nothing of European manufacture—no historical thing—to be seen.

Historical documents imply a contrast with prehistory, and nondocuments. So, despite narratives written by Spanish administrators describing settlements that are identified with specific archaeological sites, the features of these sites (not being documents, but remains of buildings) are characterized as late prehistoric, pre-Hispanic, or Late Postclassic. Late Postclassic precedes colonial in a sequence of time frames, but it is not tied to what follows, but disjoined from it: the last in a sequence beginning with Preclassic, continuing through Early and Late Classic, Early and Late Postclassic, describing an arc of history that peaked between 500 and 1000 ad.

Colonial, in turn, is never securely dated with the kind of precision found in discussions of historical documents. In one instance, the colonial period is said to follow a Protohistoric period, otherwise undefined either chronologically or in terms of specific content. In practice, materially, because only churches secured colonial identity, colonial means church, and in Santa Barbara, that means after 1552 ad. Sometimes, however, the temporality of colonial is inflected by speaking of the ‘early colonial’, implying the possible existence of a ‘late colonial’, and further underlining that the Late Postclassic is part of a series that ends and is replaced by the similarly structured early to late colonial period. Finally, sites with churches—thus, by definition, the colonial period—also appear as the historic period. Throughout, the only absolute dates used are either centuries (specifically, the sixteenth century) or specific years from Spanish documents.

Our argument is that this morass is almost unavoidable because we operate in Central America with an untenable model of history. This affects the archaeology of the pre-Hispanic period as well. Archaeologists have inherited an assumption from early anthropology that ‘traditional’ (or ‘premodern’) societies were inherently conservative, that cultural forms were aimed at warding off change. This is exacerbated archaeologically by our tendency to use specific material forms as ‘marker fossils’ for dates, part of the legacy of our methodological roots in geology. Our entire emphasis on periodization leads us to conceptualize the past in terms of segments, represented by deposits stacked one on top of another, each homogeneous, each representing a stretch of undifferentiated time. We have trouble conceptualizing how one of these periods gives way to another, leading to our emphasis on events and catastrophes, to the disadvantage of the ongoing flow of activity through which humans reproduce the circumstances of their lives on a daily, lifetime, and generational basis. The strains on our understanding of history become much more evident when the histories we are attempting to reconcile come from three different continents.

8.4 POINTS OF REFERENCE

Let us illustrate the problems in another way, by returning to the one archaeological site from northern Honduras where a long and continuous occupation from before Columbus set sail to well into the period of the modern Honduran nation has been explored: Ticamaya (CR-337) (Blaisdell-Sloan 2006). The first identification of CR-337 as possibly the site of historic Ticamaya, as we have noted, was made in 1983 by Sheptak, in an unpublished paper circulated among archaeologists working in the valley at that time. Joyce, who had coordinated the field survey in the lower Ulua Valley in the preceding years, was dubious about the ability to find archaeological sites from the sixteenth century merely by looking at places with the same names four centuries later.

Kevin Pope (1985), conducting geoarchaeological studies of rivers and their changes throughout the history of occupation, was intrigued by the evidence on air photos that showed that modern Lake Ticamaya had been formed by changes in an old drainage of the Rio Choloma that resulted in the abandonment of the course that had led it to join with the larger Rio Chamelecon north of the hills cradling the Laguna Ticamaya. On his field visit to auger the abandoned riverbanks, Pope recovered fragments of ceramics, among them larger pieces in backdirt from field canals.

The form (a ‘frying pan’ incense burner) and surface treatment (red painted motifs on white slip) of the vessels recovered at Ticamaya are diagnostic of Nolasco Bichrome, typical of Naco, located in the next valley to the west on the middle course of the Chamelecon River. In the sixteenth century, Naco was implicated in political struggles between Hernan Cortes and others he sent south, who proved disloyal to him, sparking his famous march from Mexico to Honduras in 1524. His lieutenant Bernal Diaz visited Naco itself, describing it as large and prosperous. Modern archaeological research at Naco confirmed the image of a thriving community occupied from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries (Wonderley 1981).

Based on the recovery of Nolasco Bichrome pottery, Ticamaya entered the archaeological record as a Late Postclassic site with a material record comparable to Naco. On this basis, it was selected for test excavations (Wonderley 1984). These excavations recovered an assemblage containing cattle and pig bones, metal, glass, and majolica, and lacking Nolasco Bichrome, leading the excavator to reclassify the site as colonial. Even worse, from the excavator’s perspective, the majolica suggested dates in the late eighteenth or even early nineteenth century.

Once this component was encountered, the excavator ceased work at CR-337 because it was not confirmed as a Late Postclassic site, and the research questions of his project concerned Late Postclassic and relations with Naco.

Naco itself was a significant settlement during the first century of colonization, prominent in historical documents. Nonetheless, almost nothing recovered through excavation at Naco testifies to the Spanish residents we know lived there in the early 1520s, or their successors in the early 1530s who demanded Naco’s support as they built a new Spanish town, Santa Maria de Buena Esperanza, a few leagues away. One piece of majolica was reported in test excavations in the 1930s (Strong etal. 1938). In one location, reoccupation atop a collapsed mound formed by a pre-Hispanic building was identified as later (presumably colonial) residence (Wonderley 1981). Hewing to the generalization we have drawn from our close reading of signs of temporality, the presence of a ‘Naco’ in documents, which is an historic place by virtue of being recorded by Europeans, did not make the material site of Naco historic or colonial. Like the residential structures on the Yamala River floodplain, Naco’s buildings and their associated artefacts were Late Postclassic, late pre-Hispanic, and therefore not to be linked to the historic period, represented by the objects recovered in the first test pits at Ticamaya.

When Blaisdell-Sloan (2006) returned to Ticamaya twenty years later, she did so because it was the one securely dated colonial settlement known from the lower Ulua Valley. While most of our archival research had yet to be done, what was available already showed that Ticamaya had been occupied by a leader of indigenous resistance to Spanish colonization and continued to be occupied through at least the end of the sixteenth century (Sheptak 2004). It was consequently as a colonial place that Blaisdell-Sloan approached the site. It might be considered as frustrating for her that most of her excavations lacked any evidence of European tradition goods, none producing European-made pottery or animal bones of imported domesticates, and only one yielding some fragments of non-local metal and glass. As Blaisdell-Sloan continued her excavations, she found no clear break in occupation and finally simply terminated her deepest pits when the associated ceramics suggested that she was sampling likely Early Postclassic levels.

A key issue for Blaisdell-Sloan, and for us as we consulted with her on the development of her analysis, was arriving at some way to identify occupation levels that might date to and after the Spanish campaigns in the area. She identified four different lines of potential evidence for dating the vertically stratified components she had tested: radiocarbon dates, indigenous tradition ceramic types, European materials, and stratigraphy. Eleven radiocarbon dates spanned the period from 1000 to 1100 ad to 1460-1640 ad. The temporally diagnostic indigenous tradition ceramics that she identified matched types defined for the Late Classic, Early Postclassic, and Late Postclassic, spanning a period from before 1000 ad to the sixteenth century. The only European tradition materials from the site with clear chronological placement were the majolica sherds excavated by Wonderley and glass recovered in one of her own excavations made in moulds patented in the 1820s, together suggesting dates between 1780 and 1830.

While these were the main expected temporally sensitive materials, Blaisdell-Sloan also considered whether chipped stone technology using obsidian from the Ixtepeque source, imported from the distant border of Guatemala and El Salvador, could be considered temporally diagnostic. Wonderley (1984: 71) had reported no obsidian from the house he sampled, describing the few quartzite flakes he recovered as ‘vestiges of the pre-Columbian chipped stone tool tradition’. In contrast, Blaisdell-Sloan (2006: 171) noted that ‘obsidian may have been in use as late as the

19th century____ As a chronological diagnostic, obsidian cannot be

Equated with pre-Columbian dates (since early colonial contexts yielded obsidian).’

Indeed, the most formalized obsidian tool recorded from Ticamaya, small stemmed dart points bifacially chipped on blades, was actually more frequent in apparent sixteenth-century contexts. This parallels research in Belize, where the production of these small points has been explained as a strategy of military defence against the invading Spanish (Simmons 1995).

In the end, what guided Blaisdell-Sloan’s interpretation of dating was not the potential signifiers of discontinuity—the indigenous tradition materials expected to be abandoned, or the European tradition ones expected to appear—but those measures of time that are continuous: radiocarbon dates and the stratigraphic record. What these indices showed was an archaeologically predictable pattern: In the five household areas she excavated, some were occupied discontinously from early to late; others were occupied continuously, but only in the early span of the history of the site; and still others appear to have been entirely products of human dwelling in the later centuries of the site’s history (Blaisdell-Sloan 2006). Her Operation 5 tested deposits of Early Postclassic (c.1000-1300 ad) to Late Postclassic (1300-1536 ad) occupation in an area reoccupied in the early nineteenth century. Her Operation 4 yielded only materials of apparent Late Postclassic tradition, although these were very near the modern surface. Operation 1 at Ticamaya also produced

Late Postclassic materials in its deepest tested levels, overlain in this case by other strata with very similar materials that must be attributed to the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. While Operation 1 did not produce relevant radiocarbon dates, Operations 2 and 3 did, allowing the identification of sixteenth-century (colonial) deposits overlain by later (colonial or early republican period) eighteenth to nineteenth-century deposits.

What Blaisdell-Sloan proposed was that Ticamaya be viewed as a place where distinct groups of people lived over multiple generations, so that at a village scale there was continuous occupation from long before the first European colonization to long after it, even though at any one place, this longer history might have been interrupted. While we have since refined some of the dating of deposits at the site (Sheptak et al. 2011, 2012), the major effect has been to strengthen the support for this way of viewing the site. Although we remain more tangled than would be desired in the terminology of ‘Late’ and ‘pre-’ that pretends simply to indicate relative time while smuggling in notions of progress and cultural identity, in the main, we can talk about life and historical continuity at Ticamaya throughout its known span of occupation from the eleventh century onward seamlessly. And that is true even when we add back into our consideration the part of its history not captured in the material registers recovered through excavation, that represented by documents.

In Blaisdell-Sloan’s original analysis of her excavated strata and materials, evidence for occupation in the seventeenth century was weak to non-existent. Only one excavated household, Operation 2C and 2D, had features that were tentatively assigned on stratigraphic grounds to this century, and in collaborative work we have reassigned these features to the eighteenth century based on reanalysis of the stratigraphic information. If such a gap in occupation extended to the entire settlement, it would be problematic for an analysis of persistence of indigenous communities, requiring us to consider whether, for example, the latest strata were deposits of dwelling by incomers with no historical connection to those who lived at this place before.

The evidence from documentary archives, however, shows no gap in the administrative history of the pueblo de indios, Ticamaya. Administrative records we have identified for Ticamaya extend from 1536 to 1809. Ticamaya was recorded as a tributary to Pedro de Alvarado in 1536, before his claim to be governor of Honduras was rejected, and paid tribute directly to the Crown in official registers from 1582 and 1662. In 1744, the residents of this sleepy riverside town witnessed the seizure of a boat sailed by deserting British sailors, suspected of being spies. In 1769, there are records of payment of church tithes (tercios), and in 1783 the

Residents paid a special assessment recorded in the record books of Fort Omoa. In 1791, 1801, and 1809, the population of the town was registered in censuses that continued to describe it as a pueblo de indios.

Ticamaya is, in all its components, an historic site. History, however, is something other than its usage in archaeological terminology requires it to be. Honduran historian Dario Euraque characterizes history as ‘textured’ (personal communication). What he means is that far from representing a single strand, it is a series of partially overlapping threads that take their shape on the local, familial, and generational level. Some threads, some of these localized histories, attain broader significance to people more distant from them, connected through relations of power (governance, for example) or affinity (in our case studies, religion or preferences for certain materials such as obsidian). We characterize this issue of texture as the grain of history. In some circumstances, through some material evidence, we can talk about the everyday, the day-to-day, the local generational scale; in others, we are forced to consider a less fine grain, that of political administration, legislative mandates, or even programmatic religious agendas like missionization.

8.5 TEXTURED HISTORIES AND THE GRAIN OF RESOLUTION

Archaeological histories are by their nature rooted in the local and fine grain, and it is in the local that we have the greatest expectation that our histories will be interrupted. Yet these interruptions are in no way to be equated with the kind of vast disjunctures that the language of prehistory and history, or even of pre-Hispanic and colonial, lead us to expect. The history of obsidian use at Ticamaya is, at the fine grain, a story of continued technological practice (at the very least) and possibly of continued geographic connection that evaded or better, overflowed colonial economic and administrative intentions. The histories of farming and fishing, hunting and gathering, cooking and eating, and production of pottery to facilitate those actions are also best understood at a fine grain, as histories of differential recourse to newly introduced plants and animals and use of new techniques of manufacture to make pots that would look like they always had. Histories of building and dwelling in houses, of building and worshipping in churches, set at odds with each other as evidence of prehistory and history, respectively, when seen at a fine grain are each the products of chains of traditional practices, albeit we may see a more recent origin for one than the other (see Mrozowski, this volume).

It is when we adopt a distant position with respect to lived experience that we lose the fine grain in the coarse one. There are significant transformations involved in the less particularistic history that we can tell from a regional, or even a community scale. Yet even these transformations require explanation at the finer grain of the local, lived, and generational. When we write that most residents of pueblos de indios in northern Honduras no longer spoke indigenous languages by the early eighteenth century, it is tempting to treat that as a great historical disjuncture. It is worth reminding ourselves that neither the indios themselves, nor the administrators who began to dispense with translators, saw this shift in language as ending the identity of these people or the towns they inhabited. Similarly, when we see the enthusiastic participation in Catholic cofradias in pueblos de indios beginning so early that in 1744 most communities could only report that the origins of these groups were lost in time, it is tempting to treat this as a great historical disjuncture. But again, the people engaged in these activities did not provide a narrative of conversion, and the other distinctive religious practice of the region, guancasco, shows every sign of continuing practices of inter-village relationships mediated through reciprocity in ritual.

8.6 FINAL THOUGHTS: HISTORY, DEEP AND SHALLOW

Even though we think we have learned how not to treat Spanish colonization as an event that ended prehistory and ushered in history sometime in the sixteenth century, we continue to struggle with the legacies of this mode of thought. Our original project was framed around colonization and persistence, but over and over we find that the sites and people we are studying have histories that continued long after the end of the colonial order. These histories need to be traced to the present, not left dangling like the cut ends of rope, disconnected from the people who today are seeking to understand their own society and its genesis (Aguilar and Preucel, Gould, Hantman, Lane, Lightfoot, and Walz, this volume, make similar points).

When we began our project to understand the community that built and worked around the fortress of San Fernando de Omoa, Honduras, we conceived of the study of these eighteenth-century people and their actions as providing a ‘recent past’ to supplement the ‘deeper history’ extending from 1600 bc to the sixteenth-century Spanish conquest on which we have worked for decades. Both in terms of the excavated objects of daily life, and from the perspective of archival documents recording politically and economically critical moments, the material evidence relevant to Omoa’s construction and use in the second half of the eighteenth century was much shallower.

Yet for the people who live in the town of Omoa today, that recent past is incredibly removed. Few residents of the town have roots of more than one or two generations. The familial histories they shared with us in conversation were of the decades during which the development of the fort as a national monument was a centre of contestation. This includes extremely small-scale events with dramatically large-scale implications, such as the illegal construction of a pier for natural gas shipments from Mexico around 2002 that destroyed the beachfront that had made Omoa a major vacation destination. For these people, the eighteenth century is the deep past, and even the mid-nineteenth-century material traces we have found are from long ago.

Somewhere between our recent past for Omoa in the eighteenth century, and their recent past in the twentieth century, the make-up of the community itself changed radically. So, the juxtaposition of our historical consciousnesses is not simply a comparison between the specialist or academic sense of history and a vernacular, folk, or oral tradition. The disjunction is actually evidence of history-making and history-keeping in its alternative mode, that of forgetting and erasure.

The temptation at Omoa, as in other historical archaeology practice, is to forget or deny the complicity of archaeology in coloniality; to insist that the real history that matters is the one that archaeologists recognize as significant. But the alternative is not simply, as Schmidt (2010c: 12) shows, to give over the construction of history to others, but to change our own practices, to examine what he calls ‘questions that count’: ‘those that examine the accuracy, the deeper significance, or the deleterious impacts of representations in any regional historiography’. The discussion of engagement between archaeologists and Pueblo people to identify what kinds of knowledge might be of interest is another example of changing our own practices, engaging rather than either maintaining disengaged practice or allowing a space for other forms of history while continuing our own tradition as archaeologists (Aguilar and Preucel, this volume).

In the case of Omoa, productive engagement of different historical frames is the ideal, with archaeologists producing at least one of those frames. This engagement makes clear that the more urgently needed historical archaeology there is not that of the eighteenth century, safely past for present-day Hondurans, but a nineteenth - and early twentieth-century material history that traces a time of wide social unrest during the revolutions that followed Central American independence. This is when, among other things, knowledge of African predominance in colonial Omoa town was lost as African identity was erased all along the north coast of Honduras.

What makes archaeology historical, we would suggest, is what it shares with the efforts of other human actors (not simply or primarily academics) to produce history. In this we obviously differ, as does Lane (this volume), with Gavin Lucas’s argument associating archaeology with modernity, and setting the latter off from premodernity (Lucas 2004). Archaeologists, like people at many times and places, use materialities of varying kinds to presence the past. Archival documents are, from this perspective, just another materiality presencing absent agents, demanding consideration of their circumstances of production and the kinds of agency they embody.

This is, in part, what we take Sapir to have implied in the statement, cited by Hantman (this volume), figuring documents as ‘evidence’ and oral tradition and archaeological sites as ‘testimony’. Documents come to us already mobilized as evidence for arguments, and we remobilize them as evidence in new or continued argument. Oral tradition and material residues have a different relationship to the events they index. As Ferris (2010: 14) suggests, we can avoid the ‘episodic filter’ created by Western historiographic logic and ‘develop archaeological histories that are deep, long term and that read through the episodic history...as connected to ancient and more recent pasts’.

We might instead view human experience over time as what Ferris (2010: 15) describes as ‘the ongoing process of creating and reinventing culture informed by the past’. This requires attention to subjects other than the history/prehistory dyad: memory, tradition, temporality, and even spatiality become significant for our critiques of the violence done to archaeological practice by the attempt to define and stabilize historic and prehistoric subjects.

The efforts of contemporary residents of Omoa to recount the histories that explain their own presence in the town, rooted in late nineteenth-century development of the banana industry; the representations of the tourism institute to portray Omoa as a place whose history ended in the eighteenth century; and our project’s efforts to trace the reproduction of Omoa as a place and community from colonial to contemporary periods, are all examples of memory work, discussed by Aguilar and Preucel (this volume). Memory work of this kind is effectively characterized by Ferris’s description of practices that employ ‘understood ways of how the world works—memory—to inform decisions’ in a ‘historically informed present and assumed future’ (Ferris 2010: 15-16).

It is neither the time we talk about, its distance from our presence, nor access to specific materials such as script documents that creates a common project. It is our understanding that histories are products of work through which people collectively connect their present with other times and places. As Gould (this volume), citing Pauketat (2001: 4), puts it, history is ‘the process of tradition building or cultural construction through practice’, and that is a process with neither beginning nor end.

When Michel de Certeau (1988: 4) characterizes Western historiography as dedicated to the creation of periods ‘between which, in every instance, is traced the decision to become different’, he is implicating a specific form of historical consciousness shared to a greater or lesser degree, due to our education under Western traditions of knowledge, our intensification of that immersion in higher education in an historical field, and our production of historical accounts of this form sufficiently coherent to justify publication in journals and by university presses.

As Schmidt (this volume) notes, as an historian, de Certeau proposed that the goal of writing history should be to show that ‘no society is totally homogenous and unified, that there will be new irruptions of a troubling otherness’ (Giard 2000: 19, cited in Schmidt, this volume). These ‘irruptions’ may interrupt history at the fine or coarse grain, but they are in no way evidence that history has a beginning, or an end.39

World History

World History