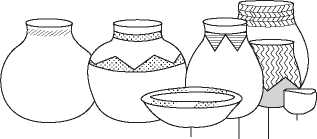

At the beginning of the thirteenth century a political change occurred as the Bosutswe elite living in the center of the hilltop aligned themselves with the elite at Mapungubwe by adopting new ceramic styles that evoked those of Mapungubwe. They further differentiated themselves from their followers by constructing large, double-walled houses wIth sunken interiors similar to those found at Mapungubwe. Commoners, on the other hand, continued to use Toutswe ceramics until approximately CE 1300. Remains of burned structures containing Toutswe ceramics on top of Boutswe date this period of transition to around CE 1200 and suggest that force may have been involved in the transformation of the hilltop from a Toutswe village, replete with houses and animal kraals, to the secluded residence of a small number of elite families (Figures 9 and 10). Late thirteenth century dates for Toutswe ceramics at CCP villages in the surrounding area suggest that a more rigid system of class differentiation developed that was similar to that now attested between Leopard’s Kopje and Leokwe peoples in the Limpopo valley.

Figure 9 Remains of a burned house containing Toutswe ceramics at Bosutswe. The burning, which dates to the thirteenth century, could suggest that the removal of commoner residences from the hilltop after CE 1200 involved the use of force. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

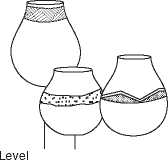

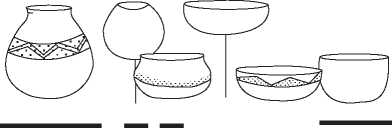

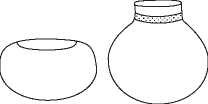

Figure 10 Changes in ceramics overtime at Bosutswe. The dramatic change in ceramic classes above level 4 date to the period when elite residences inspired by Mapungubwe were built at Bosutswe. Ceramics of Class 4d originate in the Okavango region and indicate trade westward across the Kalahari. Classes 4a and 4b, on the other hand, belong to the Leopard’s Kopje and Eiland traditions in South Africa and suggest that changes in trade networks from west to east occurred after CE 1000. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Imported glass beads, along with locally made gold, bronze, and copper jewelry, were worn by the new Bosutswe elite as an index of their status. The earliest spindle whorls date from this period and suggest that cotton cloth was worn by the elite as another mark of social distinction. Finds of bronze prills, along with the crucibles used in melting copper and with remains of iron forge bases, further suggest that

Figure 11 Agate disks recovered from a fourteenth century cache of more than 100 at Bosutswe. Such stones may have figured in rainmaking and other rituals. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The Bosutswe elite had centralized control over metal production and exchange. The high tin content of some of the Bosutswe bronze indicates it was locally produced rather than manufactured from reworked Mapungubwe bronze.

Metalworking has a well-known association with the spiritual realm in the ethnographic record and smelters, who were often associated in Central African tradition with kingship, played important roles as spiritual mediators and sometimes diviners. Other evidence suggesting that the Bosutswe elite now conTrolled spiritual resources include the recovery of a cache of over a hundred thin, snow-white agate disks from the floor of an elite structure in the center of the hilltop along with glass beads, bronze bangles, and the canine teeth from at least four hyena - an animal often associated with the supernatural (Figure 11). Such agate disks would not be out of place in contemporary divination kits or rain-controlling paraphernalia and it is possible they served these functions in the past as well.

The period between CE 1300 and 1500 saw the rise and then collapse of Great Zimbabwe to the east. While ruins of Zimbabwe type occur northeast of the Bosutswe region, and even to the west along the margins of the Makgadikgadi pans, none are known in the region running from Bosutswe to Toutswe. Bosutswe and other Lose-affiliated sites appear to have been able to maintain their distinct cultural identity while interacting with Zimbabwe communities from which rolled-rim, graphite burnished wares of Zimbabwe style, along with a lead-tin ingot, and other unusual commodities were obtained.

Figure 12 Remains of a large, circular stonewall located on an island in the Makgadikgadi pans. Local Khoe-speaking populations still leave offerings of coins and other objects at the site. © 2008 Dr. James Denbow. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

World History

World History