As our site inventory and discussion elsewhere have shown, late Pleistocene cave hyena remains have been found across most of Eurasia, fTom England to the Sea of Japan. However, not all Pleistocene cave excavations have produced remains of hyenas; Mezmaiskaya Cave in the northwestern Caucasus, for example, had no hyena remains (Baryshnikov et al. 1996). In European Russia, hyena remains have been found in the upper level of the “recent” loess of Wurm times. They have been found in Aurignacian sites in the Crimea, but not afterwards (Golomshtok 1938:221). While today these creatures have a more southerly Old World distribution, in late Pleistocene times they roamed further north. Ageeva etal. (1978) proposed that at the time of the expansion and eventual reduction of the northern Eurasian mammoth fauna, cave hyenas had lived as far as 56° N latitude (Table A1.33). Vereschagin and Baryshinkov (1984:496) agree. Law (2007: n. p.) stated that “Crocuta crocuta has been recorded from as high as 4000 meters in east Africa and Ethiopia.” Such height indicates that despite their southerly presence they have a tolerance of cold. It would be roughly freezing at that elevation when the evening temperature on the plains below was 70°F. Today, the northern limit for hyenas is about 35° N (roughly the same latitude as Cyprus and Tehran). Some 100-170 striped hyenas are thought to live in Israel (Horwitz and Smith 1988:472), and at least one of their dens has been the subject of actualistic perimortem taphonomic study (Horwitz and Kerbis 1991). Becker and Reed (1993) studied bone damage in Nubia caused by hyenas. Their interpretations paralleled those of Horwitz and Kerbis. In Russia, the cities of Moscow, Krasnoyarsk, and Bratsk are located on the fifty-sixth parallel, the northern limit of Pleistocene hyena distribution. We add for comparative purposes that also located at about 56° N is the north shore of Lake Baikal, Bering Island, Port Moller (on the Alaska Peninsula), the Belcher islands in the southern part of Hudson Bay, and Glasgow, Scotland. At this latitude continental winters are long and cold, although less so where oceanic currents introduce relatively warm water. Ageeva et al. (1978) additionally note that paleontological and archaeological finds of Siberian hyenas and other associated faunal remains suggest that the preferred hyena habitat was a sort of middle-mountainous relief covered with both steppe and forest vegetation. Such a combination of climatic latitudinal limit, vegetation-game animal associations, and foothill and low mountain cave utilization sites could have been the conditions that created the boundary across which further northward human dispersal was also challenged in late Pleistocene times. Our site backgrounds (Chapter 3) confirm the fifty-sixth parallel hyena boundary hypothesis, although we have one site (Ust-Kova) north of that latitude.

Since 1978, reports have appeared dealing with archaeological sites and their faunal contents on or near the fifty-sixth parallel. In addition to our own identifications listed in Table A1.2, we can add what S. N. Astakhov (1999) has reviewed and synthesized fTom the various excavations in the cluster of Afontova Gora sites located along and near the left bank of the Yenisei River in Krasnoyarsk - research that began in 1884 and continues to the present day. The late Pleistocene Afontova Gora large mammal inventory is familiar (mammoth, rhinoceros, horse, bison, reindeer, bear, wolf, etc.), but no hyenas. While the absence of hyena remains supports the fifty-sixth parallel hypothesis, the fact that Afontova Gora is a riverside setting could mean that its environmental conditions did not encourage hyena visitations. There are stone caves not far up-river, Yelenev, for example, so cave absence is not an issue. The finding of what is believed to be a dog in Afontova Gora may explain the absence of hyena remains as dogs could have served as sentinals and counter-hyena guards.

In addition to the sites with hyenas in our 30-site inventory, we would like to relate what Ageeva et al. (1978) had to say concerning a 1977 discovery by speleologists from Abakan, in the territory of Khakasia - namely, some details about a nearly complete, large (height at shoulder estimated to be 90 cm) and old (teeth very worn; Fig. 4.3) hyena skeleton and other animal remains at the bottom of a vertical cave trap called “Fanatic’s Cave,” the fauna of which fits the steppe-forest concept. Unlike the massively damaged hyenas of our inventoried sites, the Fanatic’s Cave animal indicates a solitary death due to its fall into the uninhabited animal trap. Other Pleistocene species from Fanatic’s Cave identified by these authors included sable, wolverine, wolf, bear, fox, and bison - steppe and forest dwellers whose presence in the trap was not fully understood. The location of Fanatic’s Cave in the Serengeti-like Minusinsk Plain of southeastern Siberia would have been a favorable area for large herds of seasonally migrating ungulates such as horse, kulan, yak, and bison, whose numbers would have provided resident hyenas and other large carnivores many opportunities for hunting, scavenging, and demographic stability, if not population size. The numerous late Pleistocene archaeological finds fTom the upper Yenisei River basin corroborate this inference of abundance (Vasili’ev 1996).

At the fifty-sixth parallel both hyenas and humans of late Pleistocene times can be hypothesized as having been intensively competitive due to limited resources. We propose that the fifty-sixth parallel was the rubicon that humans had to overcome to reach the New World, and at this latitude hyenas possessed advantages that humans lacked, most notably having the ability to hunt at night, and being climatically adapted in contrast to the “night-blind” and “tropical” humans burdened with their helpless and slow-to-mature infants. We propose that the fifty-sixth parallel marked the location of a significant barrier to human dispersal northward, as much as was the Arctic Circle at 66.5° N latitude. There, most large carnivores had dropped out of the barrier mix and only cold, long periods of mentally depressing (Arctic hysteria) darkness, and patchy environment remained as major inhibitors to human population expansion into Beringia.

Hoffecker (2005) reviews the far northern settlement by humans, which he finds to be a late human expansion.

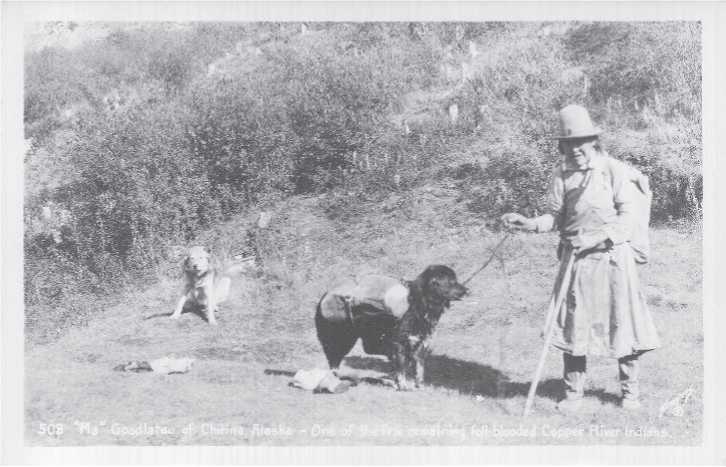

According to Kurten (1976), no fossil remains of cave hyenas have been discovered in the New World. Still, some late Pleistocene inhabitants of Siberia did reach Alaska, notably saiga antelopes, humans and their dogs. We feel that it was the fully domesticated dog that helped break through the hyena barrier and made possible the transit to eastern Beringia. One example of such aid is helping transport all the camping, personal, and hunting gear needed for human survival in the high Arctic, equipment the likes of which the Siberian Mousterians did not possess. Dogs could have been used to pull sophisticated sleds with runners across more-or-less level ice and snow (Fig. 4.4), or pull simple two-pole travois sleds, sufficient for use in grasslands, or used to carry “saddle bags” in forests, rocky terrain, and other situations. Modern Na-Dene Indians of Alaska used saddle-bag-carrying dogs, as shown in a late-nineteenth-century postcard (Fig. 4.5). Oddly, dogs seem not to have filled the imaginations of artists who have depicted the migration of Siberians to Alaska, or as aids in hunting. As with modern Eskimo use of dogs to help hunt polar bear, late Pleistocene dogs could have aided in the hunt for game animals; after all, their behavioral evolution involved hunting in social packs. Until the introduction of modern snowmobiles, dogs were indispensible for human existence in the Old and New World Arctic.

Fig. 4.4 One of several valuable uses that dogs serve across the Arctic. Malamute dog team and sled

Belonging to Patricia Bradley, driving sled. Jacqueline A. Turner and Korri Dee Turner, passengers. Temperature was ca. 0°F. Patricia Bradley is daughter of N. P. S. archaeologist Zorro Bradley and wife Natalie, Fairbanks, Alaska. These dogs are about the size of the Razboinich’ya dog (CGT color Fairbanks 12-30-75:34).

Fig. 4.5 Modern Na-Dine Indians of Alaska used saddle-bag-carrying dogs, as shown in this late-nineteenth-century postcard. Photographer unknown.

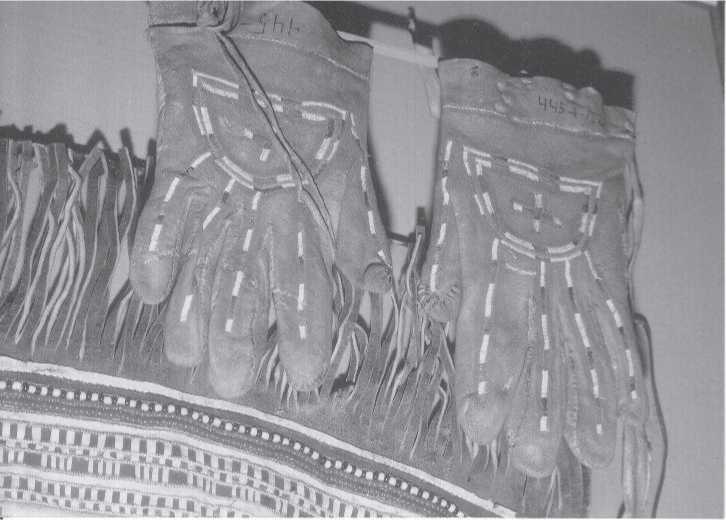

Similarly, tailored clothing was mandatory in the sub-zero Arctic winter weather (Fig. 4.6). Tailored clothing was being manufactured at least 20 000 years ago in Siberia, as evidenced by fine bone needles, such as the one we found at Dvuglaska Cave and those from Afontova Gora. We also feel that shamans (Fig. 4.7) were necessary for the Beringian trek. Their visions of where to find game and other needed resources, based on environmental cues learned early in their practices, would have enhanced the probability of group survival. Their animism was not without a pragmatic basis. In addition, their awareness of community life and individual behaviors would have served their people to cope with personal problems and the depressing low light level of winter months. Indirectly, we propose that the occurrence of a dog skull in Razboinich’ya Cave is suggestive evidence of Siberian shamanism at least 30 000 years ago.

The Razboinich’ya bear skull (Figs. 3.135-3.136) is even more suggestive of sha-manistic presence because of the widespread bear cult practiced all across the far north of Europe, Siberia, and North America (Fig. 3.137). Sokolova (2000:129) believes that the bear cult is an ancient ritual:

The similarity of rites observed among all the peoples inhabiting the vast territories of Northern Europe and North America testifies to the extremely ancient origin of these ceremonies which stem from a respectful attitude to the bear and date back to the Upper Paleolithic.

We propose that the Razboinich’ya bear skull, which has no evidence whatsoever of hyena damage, and hence must have been placed in the cave by Paleolithic humans, is direct physical evidence for Sokolova’s view. Having been found in close association with a directly dated dog skull, it means the cult could be as old as 30 000 BP.

Fig. 4.6 Finely tailored wind-tight leather clothing assembled with the aid of delicate bone needles must have been as important for survival in Siberian winters as it is for modern tribes living in the far north. Shown are beautifully crafted Evenk gloves, Anadyr River, Chukchi Peninsula. Made in the 1890s, these items belong to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg, Russia. Photographed in Smithsonian Institution’s Natural History Museum (CGT color 1-10-89:24).

World History

World History