The perimortem damage identified at Okladnikov Cave has far more carnivore processing (Figs. 3.94-3.95) than anything we had been led to expect from published archaeological accounts of the site. Clearly, the cave had been used repeatedly for thousands of years by both humans (Fig. 3.96-3.100) and hyenas. The evidence for both comes from their individually distinctive refuse types, signature perimortem damage, and from the skeletal and dental remains of both species. However, the perimortem taphonomy leads us to believe that hyena use of Okladnikov Cave far exceeded that of humans. As for the

Fig. 3.94 Okladnikov Cave chewed bone. A sample of carnivore-chewed bone fragments from Layer 6. The left piece is 3.2 cm long (CGT neg. IAE 7-22-99:15).

Fig. 3.95 Okladnikov Cave chewed bone. A carnivore-chewed rhinoceros humerus with end-hollowing and tooth scratches fTom Layer 7. Specimen is 26.9 cm in length (CGT neg. IAE 7-20-99:36).

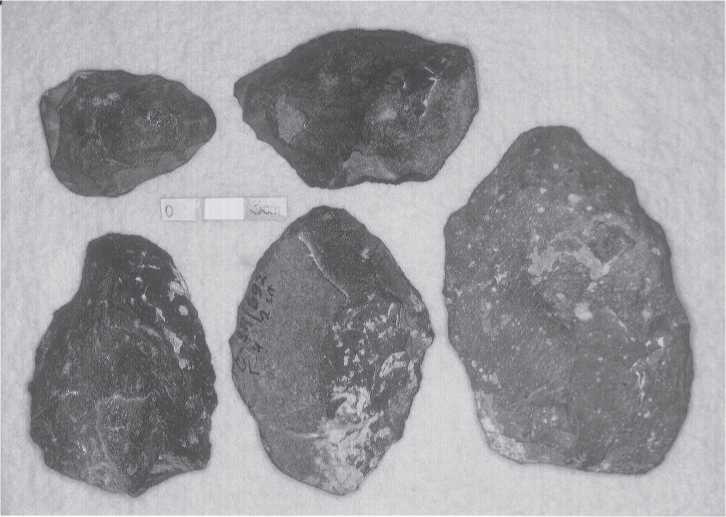

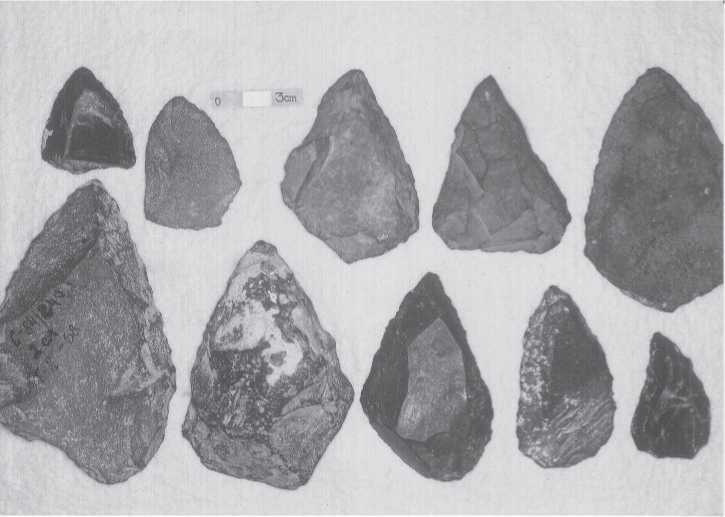

Fig. 3.96 Okladnikov Cave stone artifacts. Mousterian scrapers. These and following artifact photographs illustrate the variability in cutting edges, with no identifiable temporal significance. Scale is 3.0 cm (CGT color IHPP 6-2-87:20).

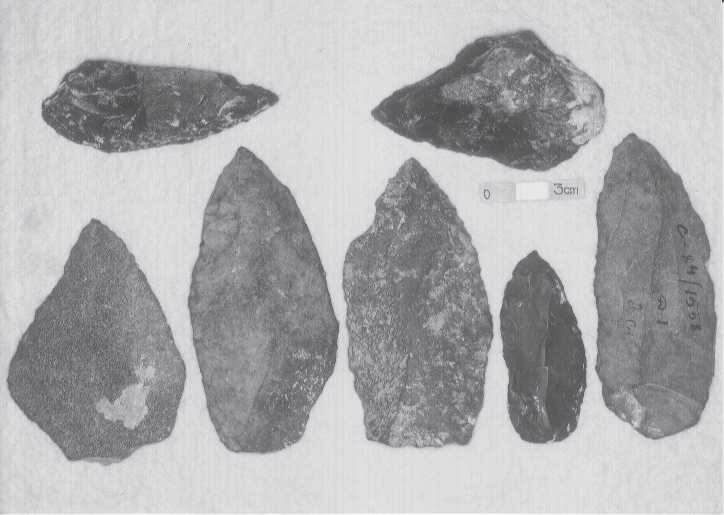

Fig. 3.97 Okladnikov Cave stone artifacts. Unifacial pointed objects. Scale is 3.0 cm (CGTcolor IHPP 6-2-87:23).

Fig. 3.98 Okladnikov Cave screblos. These knife-like unifacial tools would have left highly variable cut marks, depending on how they were used. Scale is 3.0 cm (CGT color IHPP 6-2-87:22).

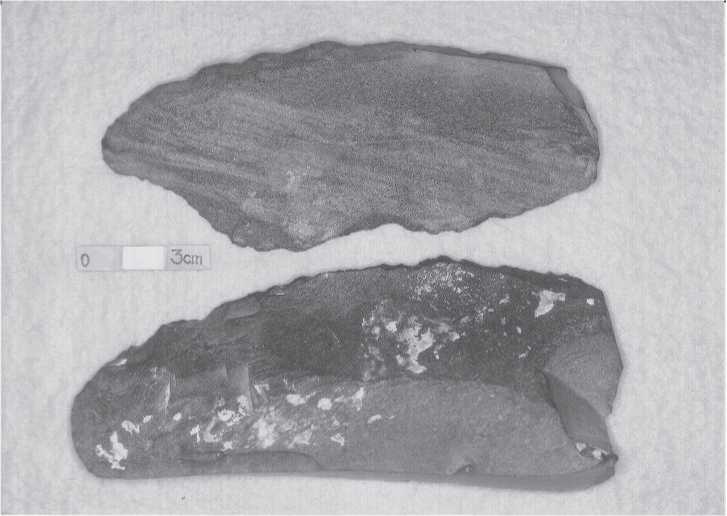

Fig. 3.99 Okladnikov Cave scrapers. There is also a small bifacial tool in the upper left corner. Scale is 3.0 cm (CGT neg. IHPP 6-2-87:25).

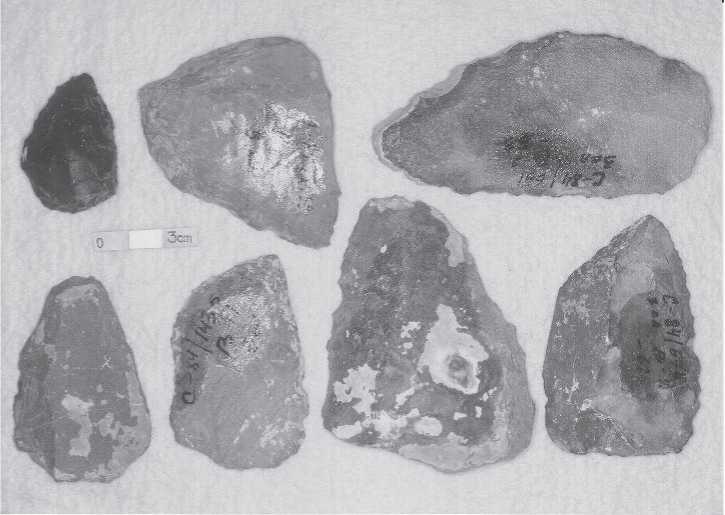

Fig. 3.100 Okladnikov Cave scrapers and points. These Mousterian tools are among the older specimens from the cave, coming ITom Layers 4-6. Scale is 3.0 cm (CGT color IHPP 6-2-87:18).

Archaeological claim that Okladnikov Cave “was used as a hunters’ site for long-term occupation” (Derevianko and Markin 1992:207), our perimortem analysis is unsupportive. One or two weeks a year, or perhaps each generation, seems much more likely if we assume that one or two bones per carcass will receive cut marks. If we assume more than two bones were accidentally cut, then the amount of time spent butchering out an animal might mean that the cave was used only a few visitations per century. On different grounds, Ovodov and Martynovich (2004:180) also found the previous quote to be unrealistic. They write:

[we made] some statistical calculations, based on the time of accumulation of Pleistocene sediments in the cave and the number of tools and [stone] waste, we have come to a paradoxical conclusion: one flake was being produced each 6 years. As P. Volkov (the only specialist in Siberia in wear analysis) thinks, 5 minutes is enough [time] for making one screblo.... About 100 flakes would be produced at that. During three to four days of experiments in his laboratory P. Volkov has produced about 10 000 flakes. Most probably, Okadnikov Cave was seldom used by humans and for a short time only.

Ovodov and Martynovich made their calculation based on the recovered 3911 stone artifacts, of which 78% were flakes, as reported by Derevianko and Markin (1992). Boaz et al. (2000) reached a similar inference in their favoring of carnivores as the primary destruction agency for bones in the Lower Cave of Zhoukoudian, rather than the result of extensive hominid processing. Regarding a Middle Paleolithic German

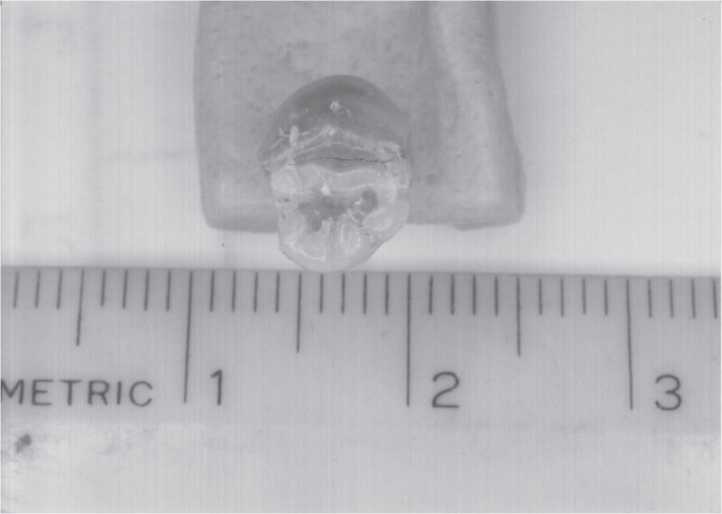

Fig. 3.101 Okladnikov Cave human tooth. This adult lower left first premolar was found in Layer 3. It is associated with stone tools typologically identified as Mousterian (CGT color Moscow 6-25-87:17).

Cave, Diedrich (2011) reviewed its bone accumulation characteristics resulting fTom hyenas and hominid occupation, an issue we have encountered with the accumulations in Okladnikov Cave.

At an international summer conference held in 2000, at N. I. Drozdov’s Kurtak field camp near the Yenisei reservoir, Ovodov gave an unscheduled report on July 29 about some of his paleontological findings with emphasis on hyenas. Relative to our concern about hyena use of Okladnikov Cave, he determined that ca. 16% (944/>6000) of the pieces of bone were hyena. Compared to a site he called “Hyena Den,” where he found ca. 12% (95 / 800) hyena pieces, it would appear that hyenas were common occupants of Okladnikov Cave.

One of the mysteries of the late Pleistocene Siberian archaeological record, at least up to now, has been the nearly complete absence of human skeletal remains, especially remains ofwhole or nearly whole individuals (Fig. 3.101-3.104). The unique exception is the largely complete older child found by M. M. Gerasimov at Mal’ta. Despite many years of excavation, as well as the excavation of numerous late Pleistocene sites, Siberia has a strikingly sparse record of human skeletal recovery, particularly when compared with anywhere else in the Old World, including Australia and even bone-destructive tropical environments such as Southeast Asia. This discovery of a strong dual presence of humans and hyenas at Okladnidov Cave provides a basis for hypothesizing on empirical grounds as to why there is a near absence of Siberian Pleistocene human remains. If

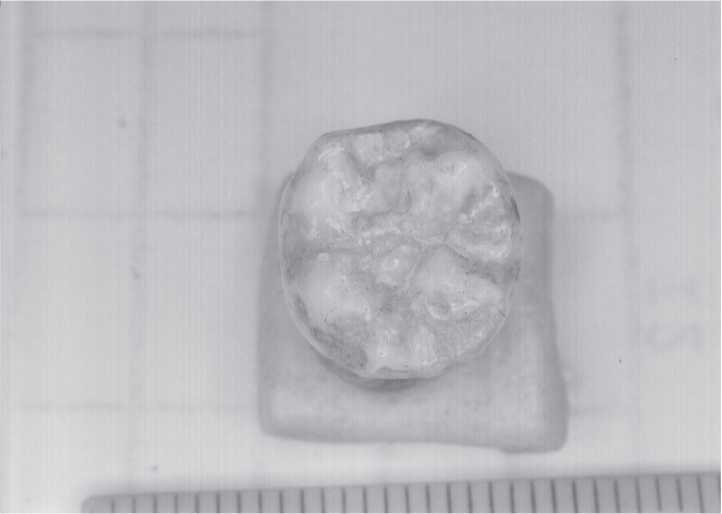

Fig. 3.102 Okladnikov Cave human tooth. This tooth, found in Layer 2, is considered by the senior

Author to be a lower left third molar of an individual who was about 12 years old at the time of death. It has no wear. The question that arises fTom this unerupted tooth is: What happened to the rest of the child’s body? Presumably the child died in the cave (CGT color Moscow 6-25-87:16).

Fig. 3.103 Okladnikov Cave human tooth. This tooth is considered to also be a lower left third molar. It was found in Layer 3. It also has no wear (CGT color Moscow 6-25-87:12).

Fig. 3.104 Okladnikov Cave human arm bones. One of the two humeri in this photograph came from

Okladnikov Cave Layer 3 (the shorter piece). The other was found by Ovodov in an animal cave he tested near Okladnikov Cave. The provenience indicated on the animal cave bone reads: “Cave, Sibiryachikha-6, Altai, 1985, remote part, red clay, with bones of hyena, rhinoceros, usv.” The humerus from the animal cave appears to be that of a child, around five years of age at the time of death. Ovodov suspects that both arm bones date around 30 000 BP (CGT color IAE 7-27-90:23).

Humans had buried their dead in the caves or in the open, we propose it possible, if not likely, that neighborhood hyenas - with their strong scavenging instincts - dug up the buried human corpses, especially those individuals who died in the winter time and would therefore have received only a shallow burial or no burial at all due to frozen ground. Hyenas today dig up relatively shallow Bedouin burials in Israel and carry away body parts to their isolated den sites (Horwitz and Smith 1988). After the end of the Pleistocene, discoveries of Siberian human skeletons are not common, but their recovery is much more fTequent than that of the late Pleistocene. Obviously, time and preservation contribute to the amount of human skeletal recovery, but possibly so also does the extinction of the Siberian cave hyena population.

Another thought triggered by the analysis of the Okladnikov assemblage has to do with seasonal or discontinuous use of the cave, since we seriously doubt that the evidence for the presence of both humans and hyenas means they lived together in Okladnikov Cave. Two lines of evidence seem most relevant. First, the small amount of burned bone argues against roasting of game and against a lot of accidental burning fTom fires kept going for human warmth all winter long. Second, the non-human teeth that were recovered with no wear or very little wear probably represent spring to fall births and deaths. Both humans and hyenas could have been the hunters or the scavengers. In either case, these game animals indicate one or the other species was responsible. The small amount of burned bone suggests humans were not using Okladnikov Cave in the winter, when camp fires would have been needed for warmth. We propose that the spring-fall kills occurred when humans would have been most likely to use the cave. Humans likely abandoned Okladnikov Cave during the winter in favor of forest camps, where fuel supplies for warmth would have been much easier to obtain. On the other hand, hyenas must have over-wintered in locations where they could obtain shelter from deep cold and lengthy winter storms. Our perimortem taphonomy suggests that Okladnikov Cave and other Siberian caves aided hyenas and other carnivores more than humans in the winter.

Finally, a few words on the controversy generated by the Okladnikov teeth, and those from Denisova Cave. As mentioned, the senior author had a very brief opportunity to examine these Altai teeth in Moscow in 1987. There was no comparative material available, neither modern or archaic humans. The few observations of crown non-metric traits that were possible followed the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASU-DAS) (Turner et al. 1991, Scott and Turner 1997). This system is concerned only with the permanent dentition of anatomically modern human populations. It does not consider deciduous teeth for various reasons (for discussion, see Scott and Turner 1997), and the standards were developed using dental casts and actual teeth obtained from around the world. In other words, ASU-DAS rigorously defines anatomically modern human dental variation. In Turner’s examination of the Altai Pleistocene teeth, it was patently obvious that these teeth had morphology far outside the range of variation of modern human teeth. Moreover, Turner felt that the morphology was more like that seen in archaic humans of Europe than in the few later Pleistocene archaic teeth of East Asia. Hence, he concluded that the Altai teeth were more like those of Neanderthals than those of modern humans of both Europe and Asia (Turner 1990c:242). In 1998 a review paper by Alexeev was published wherein he concluded that the Altai teeth were archaic but race could not be identified. Then, Derevianko and Sphakova published a reaction to the Turner paper, claiming that his study was wrong - he misidentified a deciduous molar, and was incomplete because he did not include the traits used in the Zoubov dental system. It should be noted that the Zoubov system is used nowhere outside of Russia, a criticism inconsistent with world dental anthropology, whereas ASU-DAS is used widely around the world. As for the alleged misidentification of the deciduous teeth, even if true, it is irrelevant since ASU-DAS does not deal with deciduous teeth. This critical point eluded Derevianko (2005) in his page-long critique of Turner’s observations of the Altai teeth (as much space as he devoted to criticizing Yu. Mochanov).

Why the criticism of Turner and the favoring of Sphakova’s view that the Altai teeth were modern? Sphakova’s experience in dental anthropology was not much more than that of a first-year graduate student. Derevianko (2005) provides the answer both directly and indirectly. Directly, he states explicitly that he believes in multi-regional evolution of modern humans. He rejects the out-of-Africa hypothesis that has become the major world view of modern human origins. He believes thatNeanderthals were the ancestors of modern Europeans and Siberians. Why? We reject the possibility of racial prejudice in having a relatively recent African ancestor despite the strong anti-Black sentiment throughout Russia. We suspect that his acceptance of the multi-regional view of modern human origins is colored by the work of he and his associates in the Altai caves, where they have concluded that there is stratigraphic evidence for cultural continuity from the Middle Paleolithic to the Upper Paleolithic, i. e., from Mousterians to anatomically modern humans. They see no cultural break that might indicate incoming modern people to the Altai, bringing with them the hallmarks of Cro-Magnon culture - movable art, symbolic representations, bone tools, considerable formal burials, jewelry, and other cultural characteristics ofmodern humans. In our view, cultural continuity is like a null hypothesis - it cannot be demonstrated, only, as in geology, can discontinuity be demonstrated. Okladnikov Cave stratigraphy, while appearing as continuous, was probably blurred and homogenized by the bioturbation of hyenas, marmots, wolves, hares, and other burrowing and digging animals that used the cave and fronting talus slope. As will be discussed in Chapter 4, all of the Altai caves that Derevianko and associates - ignoring the open sites that hyenas would have quickly disturbed - use to argue for cultural continuity have a significant hyena/carnivore presence, meaning that bioturbation ruined the stratigraphic virginity. Had there been a major human biological and cultural intrusion into the Altai, or elsewhere in Siberia, it would never be detected given the overwhelming presence of cave hyenas.

So, who was right in the question of dental identification of late Pleistocene humans in the Altai? First, fewer than a dozen teeth is hardly what one needs to settle this question. But, putting sampling concerns aside, according to T. Chicksheva (personal communication, August 23, 2006), preliminary DNA analysis in Germany of the Altai material suggests a “mixed” combination of Mousterian and Homo sapiens. What this means is impossible to say since the terms were not defined. But, regardless of terminology, it certainly favors Turner’s view that the Altai teeth were not those of anatomically modern humans. How this information will eventually relate to the issue of cultural continuity remains to be seen - hopefully before this book is finished.

In sum, we regard Okladnikov Cave as more of a paleontological site than an archaeological one. Indeed, humans did use this rock shelter on occasion, of that there is no question. These people possessed a Mousterian tool assemblage, and in the senior author’s view, based on dental morphology, were more likely to have been closer to European Neanderthals than to anatomically modern humans. Because of the substantial use of this cave by hyenas and their likely bioturbation of stratigraphy, the cave and its cultural and physical anthropological contents is not a good resource for the theoretical discussion of cultural and biological continuity, or multi-regional evolution in Siberia. This is particularly so since it seems to lack an Upper Paleolithic component and dates. It is Ovodov’s view, which we share, that the density of the Mousterian population in the Altai was less than that of cave hyenas and much less than that of a number of herbivores.

World History

World History