The utilization of dung from farm animals could be effected in one of several ways: the animals could be turned out onto harvested or fallow fields, thus fertilizing arable land before ploughing and at the same time resting the normal pasture, or beasts (and this applies particularly to sheep) could be penned up in particular areas for a period of intensive manuring.102 A third way is by the collection of dung from byres in which animals were kept in winter, which would then be spread over the fields before early spring ploughing.103 Certainly one or other method would be used before either autumn, winter or spring ploughing. If an animal is corralled overnight, most of its dung can be collected without too much effort; Peter Reynolds's calculation of dung production per cow per day is an average of 25kg.104 At Danebury, the dung of sheep, which is manure of high quality, was invaluable in its addition of nutrients to the thin chalk downland soils.105

The benefits of manuring were recognized long before the Iron Age. The dung of goats, sheep and horses was probably valued most, followed by that of cattle and pigs. As well as being applied directly to the fields, manure could first be burned and its ash spread onto the arable land. Burning dung was also a useful source of fuel: this practice is widespread in Europe and beyond, from India to Iceland. It was a common source of fuel in Scandinavia and northern Britain.106 Traditionally, dung is collected by women and fashioned into 'cakes' or 'bricks' for burning. I have witnessed women rolling dung in this way on the edge of the Nile at Tel el Amarna in southern Egypt. That dung was likely to have been put to this use in Iron Age Britain is suggested by the identification of dried-out cow-dung at the pre-Roman Iron Age site of Hawk's Hill in Surrey.107 The dung was probably stored for a while before use, since the drier it was the better it would burn and, in any case, fresh dung damages the grass on which it lies.108

Ploughing, reaping and threshing

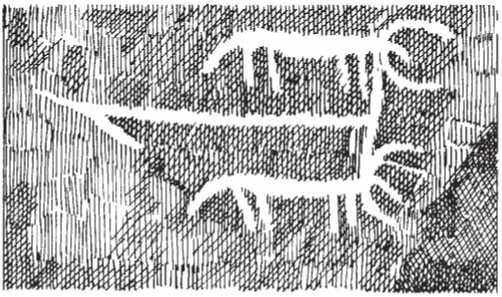

The Bronze Age rock art of Scandinavia and Camonica Valley depicts scenes of ploughing, using a simple plough or ard drawn by a pair of cattle. One Camunian scene shows two oxen drawing the plough, accompanied by the ploughman, who is walking behind. Two other men are also depicted, one in front of the animals, the other behind the ploughman. The individual at the animal's head carries a kind of mattock or hoe, as does the person at the rear of the group; the leading man also bears a twig or branch (figure 2.17).109 Reynolds has observed a similar scene in present-day rural Spain, where peasants break up the clods of earth before and behind the plough and where one man walks by the animal's head to brush off flies with a kind of fly-whisk or swatter. In the Camunian scene, the ploughman carries a stick, which is generally interpreted as a goad, to keep the cattle moving. But in Spain a stick is used by the ploughman to free the point of the plough periodically, as it becomes bogged down in heavy soil.

The evidence for Iron Age ploughs is scanty, because they were made of wood and do not generally survive, though by the third century BC in

Figure 2.17 Ploughing scene, on a Bronze Age or Iron Age rock carving at Camonica Valley, north Italy. Paul Jenkins, after Anati.

Britain, ard-shares were tipped with iron and these parts sometimes turn up as finds on sites.110 We do have the evidence of the rock art, where the plough is depicted as a simple angled spike or 'ard'. Wooden ards like those carved on the rocks are found preserved in the waterlogged conditions of peat-bogs, especially in Denmark: the Donnerupland ard, found in a Danish marsh, has been reconstructed and used in experimental farming, where it was found to be extremely efficient.111 In Britain, evidence for Iron Age ploughs exists mainly in the form of score-marks; an ox-drawn ard was used at Danebury.112 The simple plough or ard was an uncomplicated implement consisting of a wooden shaft ending in a spike set at an angle, sometimes iron-tipped, which simply stirred and made furrows in the soil. The ard is distinctive in possessing no mouldboard or coulter for turning over the earth. However, there is some evidence from the later Iron Age that fairly heavy soils were none the less being exploited.

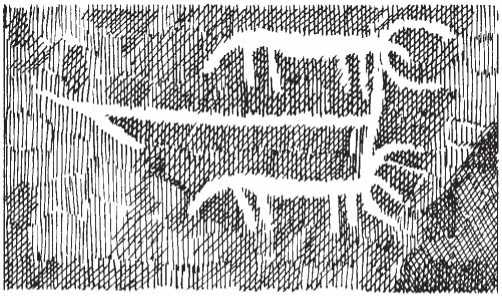

Cattle or horses could be used in ploughing: the bone evidence of horses suggests that they were sometimes used for this purpose.113 Again, a later Iron Age Camunian rock-art scene depicts a plough pulled by horses.114 But most farmers undoubtedly used cattle for traction (figure 2.18). The presence of middle-aged or elderly cattle on archaeological sites implies that they were worked before they were eaten. Such is the case at the habitation site of Variscourt; and at the sanctuary of Gournay, the cattle had undoubtedly been used as working animals before they were sacrificed to the infernal gods.115 For successful ploughing, it is necessary to have a pair of specially trained animals, with the correct size to power ratio. Peter Reynolds has calculated that the average Celtic field (for which there is archaeological evidence in Britain) can be ploughed in a single day.116 The cattle used for traction were probably kept apart from the herd, controlled and specially tended.

Figure 2.18 Rock carving at Camonica Valley, depicting two oxen pulling a plough. Paul Jenkins.

At the Butser experimental farm, two of the slender, long-legged Dexter cattle were trained as a working pair for ploughing. It takes about two years to train these animals to work in unison as a team, yoked together, to pull a light ard.117 Reynolds has found that cattle are difficult to train and can be quite intractable, requiring a considerable period of handling before being introduced to each other, the yoke or the plough. What is interesting about the work at Butser is the conclusion that many plough teams may well have been cows rather than oxen, because they are more amenable to training. The two animals could be yoked together by either a neck or a horn yoke: both methods were used in the Iron Age and are indeed both still employed in modern peasant farming.118

Animals were also required for their pulling-power at harvest time. Certainly, by the Romano-Celtic period, reaping-machines pulled by horses, donkeys or mules were known in northern Gaul and depicted on such stone sculpture as that from Reims and Buzenol-Montauban.119 After the corn had been cut, oxen or horses would be needed to carry the harvested crop away from the fields to the farm for processing and storage. The scenes on the rocks at Camonica show a number of light, four-wheeled wagons pulled by horses or cattle (figure 2.19). These vehicles could represent the transport of corn, hay or other produce.120

After harvesting, the grain had to be extracted from the raw corn. Although threshing can be carried out efficiently with flails, it can also be done by allowing farm animals to trample over the harvested corn.121 Right through the farming year, therefore, from the initial manuring of the fields and ploughing to the harvest and even after, animals were closely linked with humans in nearly every aspect of crop production.

Figure 2.19 Wagon-pulling scene on a rock carving at Camonica Valley.

Paul Jenkins.

World History

World History