This river-deposited bone accumulation provides a paleontological comparison for the archaeological sites, just as do the hyena caves. Deposition, post-depositional re-exposure, and collecting procedure have each probably affected the condition of the assemblage. Selection favoring larger-sized pieces over smaller ones must have occurred for each of the three processes, with moving water (river current and waves lapping against the bluff most of the year, and ice scouring during spring break-up) carrying off small bones and pieces of bones. By the time Vasiliev made his many collecting visits to Krasny Yar, many of the smaller items had been removed or reburied by the swiftly flowing Ob River, or simply missed because of their near invisibility in the gray-brown beach silts.

In his discussion ofwolf-pack kills on frozen lakes, Haynes (1982:279) suggests that:

On interior lakes and sloughs that are not disturbed by high energy drainage currents, bones left on the ice by predators tend to float on ice rafts during spring thaw, rather than simply dropping to the bottom where the ice is not thick or the water too shallow to float it, some remains may settle gently into the bottom during the thaw, forming discontinuous beds atop earlier skeletal deposits.

The extensive faunal deposits at Krasny Yar, including large animals like mammoth, may have ice-rafted to the site, as well as having accumulated by other natural processes. Our damage observations do not shed much light on which of several depositional processes

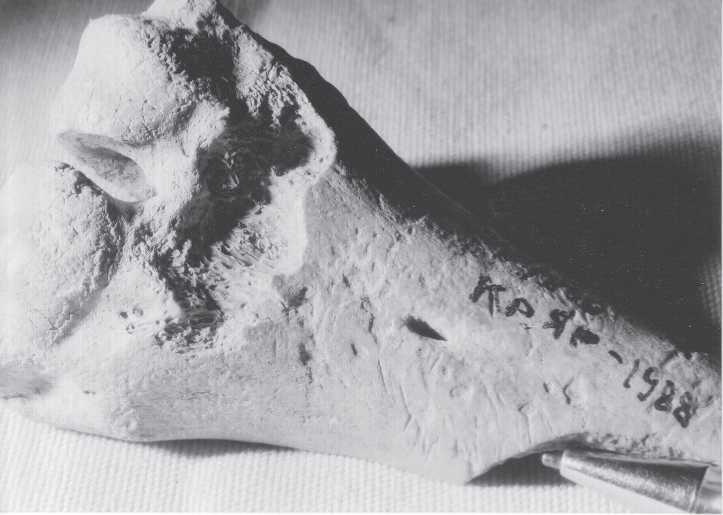

Fig. 3.64 Krasny Yar animals. The striations at the pencil point on this 7.0 cm long reindeer metapodial were judged to be cut marks, although there is a chance they are pseudo-cuts. Uncertainty in the identification of the few cases such as this arose fewer than one in 100 times (CGT neg. IAE 6-21-00:25).

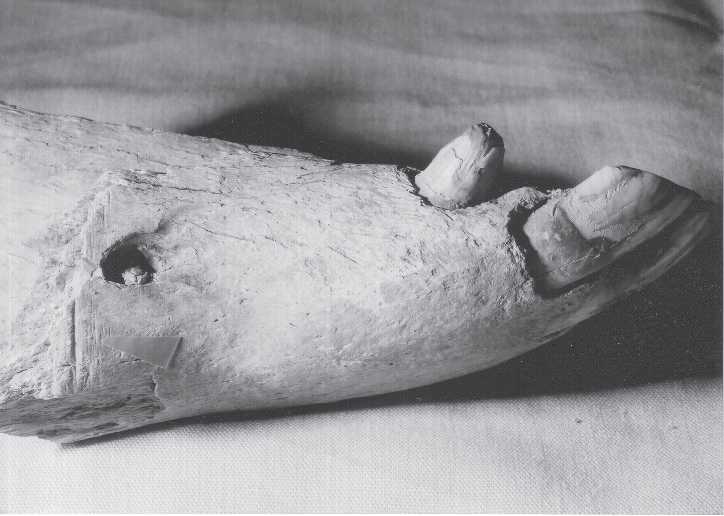

Fig. 3.65 Krasny Yar animals. There is no doubt about these striations being cut marks. The longest cut on this horse mandible (specimen 3328) is 1.6 cm (CGT neg. IAE 6-20-00:5).

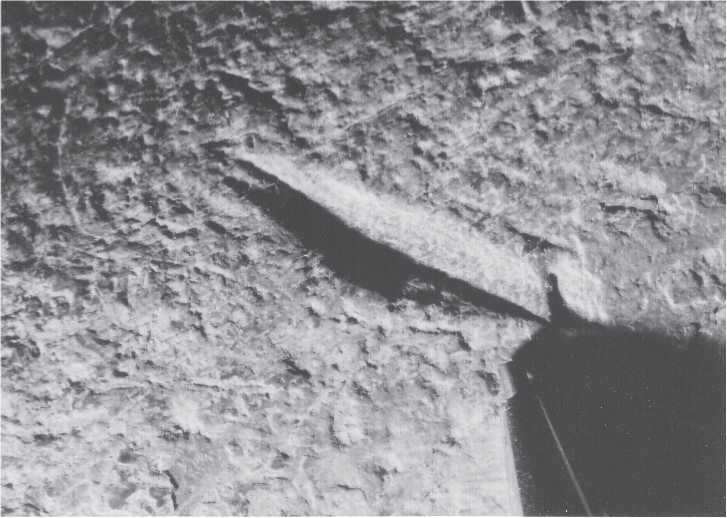

Fig. 3.66 Krasny Yar animals. A rhinoceros distal humerus with a 2.0 cm long cut mark. Total bone length is 29.5 cm (CGT neg. IAE 7-4-00:33).

Were mainly involved in the accumulation, although ice-rafting into a slough or still embayment is an attractive idea.

While the content of Krasny Yar is patently of importance for paleoecological studies, it is the perimortem damage that is our main interest in the assemblage. Of this damage, most unexpected was the substantial amount attributable to carnivores. We cannot identify exactly when in the death history of these animals the carnivores were active; however, two scenarios seem equally possible: First, the damage represents processing at the time of death, that is, initial and early perimortem. In this instance all large carnivores are equally good candidates for the damage - lions, hyenas, wolves, etc. The various carcasses in various degrees of completeness were then transported an unknown distance by water over an unknown period of time to Krasny Yar. Also unknown are the geomorphological conditions that favored the accumulation of the bone bed. At the time bone accumulation occurred at Krasny Yar the site might well have been a slough or a sand bar, like many along the Ob River today. After thousands of years the bones are re-exposed as the Ob River washes away the sediments that had buried them at Krasny Yar.

The second model envisions the carnivore damage having occurred in later perimortem death history. This model offers no explanation for the animal’s deaths, but sometime after dying their carcasses are chewed on by scavenging carnivores, which in accord with the damage signature would likely implicate hyenas to some degree. Transport again occurs where bones are deposited at Krasny Yar to be buried and later re-exposed.

We have tried to estimate from the amount of polishing and abrasion how far the assemblage traveled before reaching its burial site at Krasny Yar. Judging fTom the amount of bone polishing in various of our open sites, where movement must have at best been only a few meters and trampling of little consequence, the Krasny Yar location could have been very near to the death sites of the assemblage, say within a kilometer or so. If this estimate is at all reasonable, then the geomorphological setting of Krasny Yar might have been like that of a lake shore or abandoned river loop rather than the high-energy river bank condition of today. To put it another way, Krasny Yar might have been a freshwater muddy slough counterpart to the tar traps at the La Brea animal pits in southern California. However one interprets the taphonomy of Krasny Yar, it marvelously illustrates the sort of concerns about deposition and association that Yefremov (1940) expressed when he proposed his definition of taphonomy.

World History

World History