The history through space and time of advanced big game hunting starts with the Gravettians of 25,000 BCE and ends with the Plains Indians in the Americas in the nineteenth century ce. It is not a direct lineage, but does constitute the longest set of catenated continuities in the history of mankind. How the Plains Indians came into existence is known only in general terms. The hunting tradition came to Alaska around 12,000 bce with some of the oldest camps found in the Tanana River valley between the Alaska Range and the Tanana-Yukon Upland. People hunted wapiti, bison, and mammoth. Some hunters made it to North America, which was largely steppe and grassland with the first bison-centric culture taking shape around 9000 bce. By 5000 bce the Plains Indians had probably developed their cultural uniqueness, which remained more or less continuous until the introduction of corn into the region around 1000 ce and horses around 1600.25 In some places, tribes became semi-sedentary around corn-growing areas. Other tribes remained largely migratory. Some of their names are Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Lakota, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, and Sarsi. Whereas many were native to the plains, in particular those known collectively as Sioux, not all lived with the bison since ancient times. The Cheyenne, for example, were newcomers into the region. The word “Cheyenne” is a Sioux name meaning “people speaking language not understood.”26 The reason they were not understood was they had migrated into Sioux area from the Ohio Valley far to the east. They had originally been sedentary, planting corn, squash, and beans, and harvesting wild rice. But ecological changes expanded the grasslands of the prairie in the seventeenth century, forcing the Cheyenne to adopt the Plains Indian lifestyle. With the introduction of horses in the seventeenth century, the Cheyenne abandoned their farming lifestyle altogether and became a full-fledged Plains horse culture.

The Sioux are considered among the most typical of the Plains Indians. Their society, prior to the advent of the horse, consisted of small, close-knit family hunting groups with a patriarch at its head. The primary type of residence was the fipi.27 The Crow call the tipi ashe (home) or ashtdale (real home), but the word tipi comes from the Lakota word tipestola. Though clearly derived from prototypes developed thousands of miles away before humans even set foot on the Americas, it is a local development that probably took its shape around 2000 BcE if not earlier. Although superficially similar to the Siberian conical residence, the tipi is on closer inspection quite difierent.

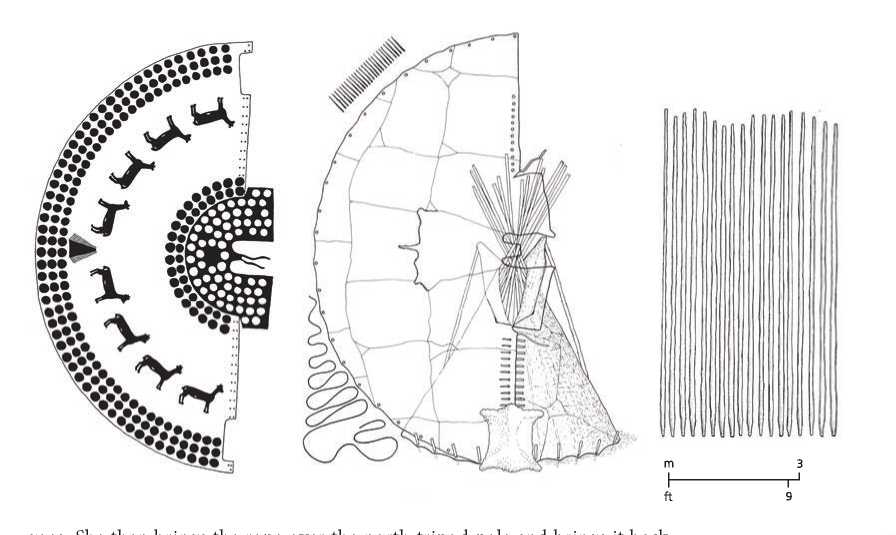

The most ingenious aspect of the tipi is how the open fire in the center of the tipi is dealt with. If the tipi were a true cone, the smoke hole would be at the center around the poles meaning that the structure could never be closed in wet weather. In Siberian structures this is simply accepted. But the Plains Indians solved the problem by tilting the cone of the tipi so that it has a long side, which is the front, and a short side, which is the back. This then shifi:s the location of the smoke hole to the long side of the tent, just below the apex. It is thus possible to close the top as tight as possible, while also allowing for flaps to open or close the smoke hole. Some tribes tilted their cones more than others. This explains why the plan of the tipi is not circular but oval.

A second innovation was in the construction method. Siberian cone structures are formed by leaning poles against each other and then tying them together with leather straps or horizontal bands. The tipi, by way of contrast, has no horizontal elements whatsoever. So what gives it structural integrity? The answer is the skin. Each tipi is custom-designed with a skin

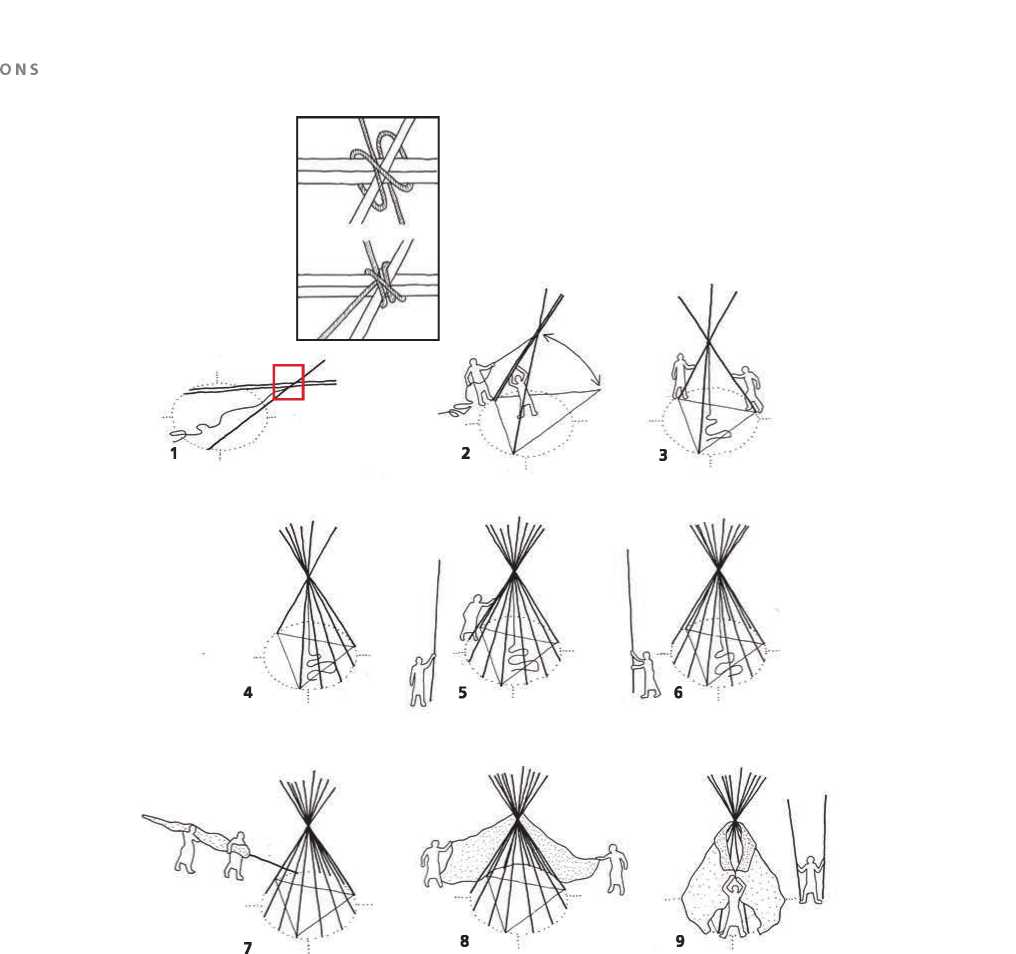

Figure 4.23: Tipi construction sequence. Source: Andrew Ferentinos, Paul Goble, Tipi: Home of the Nomadic Buffaio Hunters, World Wisdom, 2007, pp. 28-29

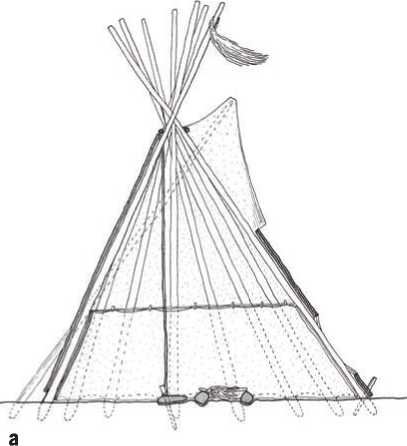

That fits like a tight jacket over the poles, in that sense it is fundamentally different in conception from the Siberian prototype where the skins are draped over the frame and then tightened to it. The skin of the tipi is akin to a piece of clothing. Another innovation was at the beginning of construction. For a chum, erecting the three poles will usually need at least two people. The tipi can be erected by one person. The three poles, lying on the ground, are joined at the apex by a cord, which is then pulled up to make the frame. There is a four-pole type and a three-pole type of tipi, the latter used by Sioux, Cheyennes, Omahas, and others. A tipi can be 6 or 7 meters in diameter, but some can be as large as 10 meters in diameter (Figure 4.23).

Once the poles are elevated into position, the other poles are added to complete the circle; the builder then grabs the rope, dangling in the center, brings it to the outside and winds it around the bundle of pole at the apex by walking around the tipi, tightening the rope as she

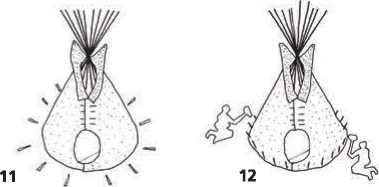

Figure 4.24: Tipi parts and skin. Source: Andrew Ferentinos, Paul Goble, Tipi: Home of the Nomadic Buffalo Hunters, World Wisdom, 2007, p. 13

Goes. She then brings the rope over the north tripod pole and brings it back into the center, where it is pegged into the ground to serve as a brace against the wind. Ropes were made from buffalo hair and strips of hide.

For the poles, usually pine was used or, where available, cedar, which is quite light and strong. The tribes of the southern Plains preferred poles of red cedar, which were weather resistant and lighter than pine. Fir, if it could be found, was even lighter. Since such wood was not found on the open prairie, it was often acquired in trade with people to the east or west. Cedars require a great deal of trimming at the butt end to make them a useful size. The poles, usually gathered in the early spring, must be stripped of bark and smoothed of imperfections. Fifteen poles are needed for the frame and two for the smoke flaps. The poles as they are dragged from camp to camp become shorter and shorter until unusable. For that reason, the poles are cut with length to spare and thus new ones will project 2 to 3 meters beyond the top of the tipi.

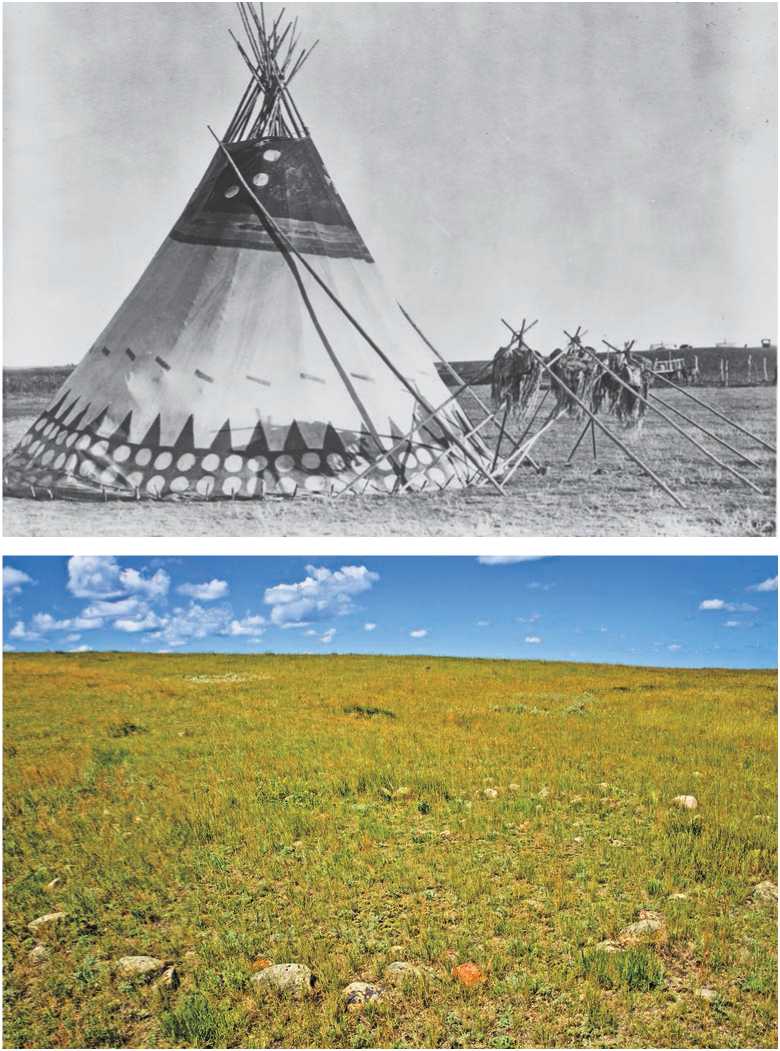

The cover is created in the shape of a semi-circle with flaps and attachments already in place. It is woven from different cow hides and in essence preassembled with all the appropriate holes and stitchings. Among some tribes, only a woman with special privileges could cut and size the covering, but once it was laid out as many women as possible were invited to assist in the sewing, for which they received a feast. The covering was not just the shield against weather. It was a sacred surface, with the smoke flaps called arms. When completed, the cover was soft and white, but after a year or two of exposure to the elements and smoke it became discolored. It was commonly cut up for moccasins.28 Men would sometimes paint the covers with war records and other insignia identifying their clan and its history. For construction, the cover is bundled up around a pole and leveraged into place along one side of the structure, unwound around the tipi, stretched over the framework and then “buttoned” down the front. The base is anchored by stones. In warm weather, the base can be left open for a breeze to come in. When properly built and secured, a tipi is remarkably wind-resistant.

During the winter, the insides are lined with a skirt of furs and hides that also helps with ventilation. The warm air rising in the center draws in cold air from under the tent. The airspace behind the lining serves as insulation. The lining also serves to help in privacy and security. Under attack, an enemy would not know who was in a tent or whether it was occupied at all (Figures 4.24, and 4.25a, 4.25b).

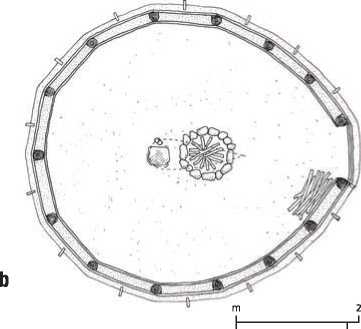

Figure 4.25a, b: Tipi: (a) plan, (b) section. Source: Andrew Ferentinos

When taken apart for transport, the whole package can weigh 400 pounds, so before the use of horses the effort of erecting the tipi paled in comparison to the labor of moving camp. There were no pack animals, so dogs were often used to help move the bundles.29 Early Spaniards tell of five hundred dogs in a train.30 Once horses were plentiful on the Plains and could be used for transport, the tipi spread to the Dakotas east of the Missouri River and west to the Utes and others. The tipi was meant to last as long as possible. The reason is quite clear. Forests were rare on the open plains, meaning that habitation had to be not only transportable, but also durable. The Plains Indians, one can say, had a lifestyle that was migratory, but an architecture that was both transportable and relatively permanent.

It is the woman who owns the tipi, with the exception of the tipi of the medicine men. The woman is also responsible for its construction, which she can do in about twenty minutes. Crooked or poorly trimmed poles gave the woman a bad name. It would have been

Figure 4.27: Women in a tipi, South Dakota, USA. Photographed in 1891. Source: Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-749

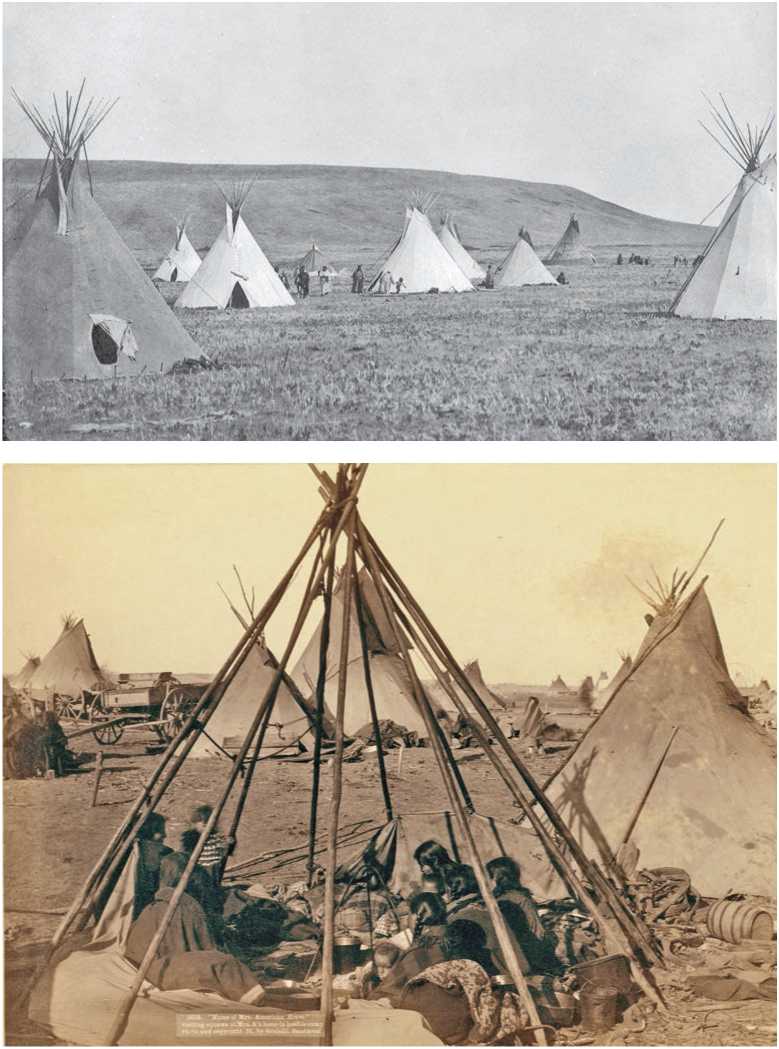

Figure 4.26: Atsina (Arapaho) camp scene, Montana, USA. Photographed in 1908. Source: Edward Curtis Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-66669

Beneath the dignity of a warrior to take part in the erecting of a tipi (Figures 4.26, 4.27, 4.28, and 4.29).

The tipis are, of course, cosmological plans, usually arranged facing east. The interior, in the Siberian hunter tradition, is centered on a fire and behind it an altar. The altar is not an architectural object, but a demarcated spot in which sacred grass is piled and lit, filling the tipi with its sweet scent. When moving inside the tipi, one never moves between a person and the fire, at least without asking permission. One moves behind a person, with the person leaning in a bit. Rules about entering vary from tribe to tribe. In some places, everyone moves in a clockwise direction to their spot. In other places, women move to the left: and men to the right. Sleeping and sitting arrangements also sometimes vary, but usually men are to the right of the entrance, the most important spot being next to the north pole of the tripod. The oldest male usually slept to the north, women on the south.

Figure 4.29: Tipi ring, Saskatchewan, Canada. Source: Gord Hunter

Figure 4.28: Lodge of the Horn Society, Alberta, Canada. Photographed in 1927. Source: Edward Curtis Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-101190

World History

World History