The Mijikenda (“the nine tribes”) are nine ethnic groups who live along the coast of Kenya, from the border of Somalia in the north to the border of Tanzania in the south. Although these groups have often been called the Nyika or Nika by outsiders; the word is a derogatory one meaning “bush people.” The designation Mijikenda was adopted in the 1940s. They are hardly “bush people” but controlled the coast and ports. Socially they are agro-pastoral, growing sorghum and millet and also raising cattle, sheep, and goats. Their history is not well known, but it is generally assumed that their ancestors lived originally in Somalia, but moved down the coast in various waves from the tenth to the sixteenth centuries. There they served initially as trade intermediaries between the coast and the hinterland, living in fortified towns. They grew palm groves to produce uchi, a type of palm wine that was used in rituals, libations for the dead, and bridewealth payments. The palm is referred to as “the mother” but only men could own palm trees.13

Each of the Mijikenda groups has a sacred forest called the Kaya. These forests serve as ritual centers for the community. Some still exist on the outskirts of Mombasa. As is typical in such situations, one needs a guide or a “host” to enter the forest. This usually consists of a Kaya Elder with whom a visitor will have to consult and ask permission. To fail to do this before entering represents intrusion and may precipitate harm to the community but particularly to the intruder. The Mijikenda say that in olden days, enemies were blinded in this way and failed to find the hidden villages due to the powerful protective magic of the Kaya. To enter the forest one must also use a particular path that has been maintained through the ages. There are several gates and conceptual thresholds that the path crosses. There might be a receptacle at the site of a gate that holds protective charms and where small ofierings can be deposited. On the outer side of the gates on one side of the path, there are historical burial grounds. At the

Side of the path there are also small booths made of thatch in which there will be small platters of food. This is the Kadzumba ka Mulungu or “house of the spirits" usually placed at a spot known as a Kiza, or place of sacrifice. The Kiza is usually located under the shade of a large fig tree or baobab. The purpose of the ofierings is to entice and divert malevolent spirits from proceeding into the Kaya and disrupting an ongoing ceremony. On passing through the last gate site, one will finally enter the Kaya or the historical village, surrounded by a thick protective fence or stockade of poles and tree trunks, allowed to rot away. Nearby there may be old palm groves. Little or nothing remains of the village dwellings except for the clearing in the forest. If the Kaya was recently used for a ritual, it will have been cleared of grass and weeds and there will be one or more ceremonial thatched huts. The poles and thatch for them will have been obtained from within the forest as no materials are allowed from outside. There will also be traces of fires recently lit and remains of food partaken. The former site of the village meeting booth or hut, the moro, is of particular importance. The moro was where all issues afiecting the whole tribe were discussed together. From time to time, replicas of these huts are built for ritual purposes. The holy of holies of the forest is the fingo, the forest’s special protective magic. Its location can never be disclosed to anyone outside the village. No one was permitted there, and those who blundered into it were not expected to live. Apart from the fingo there may be other sacred spots including the burial sites of past spiritual leaders. Hidden away from the central clearing also is the site of the tutu, a ritual hut where only select elders met for secret discourse and where oaths were administered. In addition to these elements of the forest’s sacredness are the numerous natural phenomena that have spiritual associations. These include springs, large rocks, caves, clifis, and trees of great size. Nothing must leave the sacred forest. Enforcement of rules is mainly through a system of taboos, curses, and other spiritual sanctions, which still have a powerful efiect in the rural communities associated with the Kayas14 (Figure 15.18).

Figure 15.18: Mijikenda, Kenya, a typical sacred grove. Source: Andrew Ferentinos

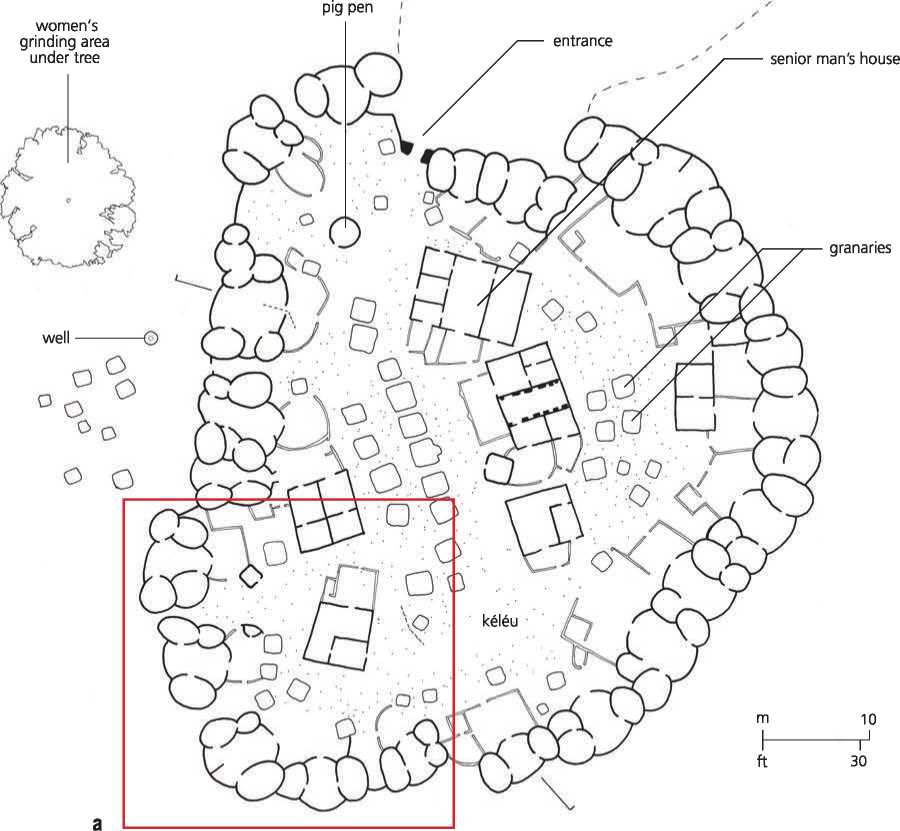

Figure 15.19a, b: Gurunsi village, Burkina Faso; (a) site plan, (b) section. Source: Timothy Cooke/Jean-Paul Bourdier and Trinh T. Minh-ha, African Spaces (New York: Afri-cana Publishing Co, 1985), 35

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](https://www.worldhistory.biz/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)