Good clothes open all doors. —Thomas Fuller

When I look at archaeological and ethnographic collections, I am always taken with the fact that each object seems to carry several layers of meaning. Objects such as the Native Alaskan necklace in Figure 5.1 do not fall neatly into categories constructed by my museum predecessors. If this object had been lost, discarded, or buried with its owner, we would have known it in the archaeological record only through its components: faunal remains, a carved ivory needle case, a brass bead, a brass finger a ring, a crucifix, and a Chinese coin. The original strip of leather onto which each item is strung is intact. Because this object is still in it original form, we have an opportunity to interpret the components of the necklace both separately and, more important, in relationship to one another. While the motivation for placing a crucifix on a necklace with a Chinese coin and a small animal skull is unknown, it is clear that the act of making this necklace and wearing it was significant for the owner. Each component of the necklace—the crucifix, the animal bones, the ring, even the brass bead—is a meaningful piece of adornment in its own right, but when layered together each component adds to the power and impact of the necklace when viewed together as one item. In this way the necklace speaks to us about the intent of its maker, how this individual drew from several different cultures to make a necklace intended to be worn in the colonial world.

This necklace is just one visual reminder of the ways in which colonial peoples pulled together different fashions to mediate their place in the colonial world. The diverse ways that colonial peoples expressed themselves through clothing and adornment offer a discourse of identity in the context

5.1. Necklace of leather thong with bone, animal teeth, ring, metal cross, and coin, nineteenth century, Northwest Coast. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 38-44-10/12889.

Of colonial projects that were fraught with regulations, tensions, anxieties, desires, and tastes. While the necklace may have been similar to other objects in colonial America—for example, the octagonal cuff links found in New York and Massachusetts—the ways these objects were used were specific to their context and were meaningful to those who created and then viewed those fashions.

This point is illustrated in the archaeological work that has been done on the clothing and adornment of enslaved Africans and African Americans. Anne Yentsch’s (1994) examination of clothing and adornment artifacts recovered from the Calvert site in Annapolis, Maryland, has enabled her to bring forth various stories of dress that have been lost in documentary sources. Glass beads that adorned the necks and wrists of African women and children and clothing fasteners adorned with a hand to protect the wearer from the power of witches have been recovered in the mid-Atlantic colonies in particularly meaningful ensembles (Yentsch 1994:33). Whites dismissed such objects as baubles but allowed African women to use glass beads to express themselves visually (albeit silently). These kinds of dress were a visual discourse, a way to communicate self with those that understood the meaning of such forms of clothing and adornment. Similarly, Alexandra Chan (2007) analyzes items of clothing and adornment recovered in a slave context in Medford, Massachusetts—for example a small stone bead crafted by an enslaved African—in the context of a dialogue between the individuals who occupied Ten Hills Farm: the Isaac Royall family and 63 enslaved individuals of African descent (Chan 2007:93-94, 140). In both of these examples, enslaved Africans wore clothing that was in some sense similar to the clothing worn by those who were enslaving them. But the African Americans constructed their dress using combinations of clothing and adornment that carried multiple layers of meaning.

In this section, I discuss two different assemblages of clothing and adornment artifacts: the first from Dutch New Netherland and the second from French Louisiana. In these examples, I explore the meanings that different combinations of European-manufactured and Native American-manufactured items held and how these objects were part of a social discourse and were mobilized to create specific identities in the colonial world. In the example from Dutch New Netherland, I begin with a relatively small collection of items of clothing and adornment recovered from household contexts, while in the example from French Louisiana I focus on a larger assemblage of clothing and adornment items recovered from domestic and burial contexts. My goal here is to problematize these two assemblages, consider some of the existing stereotypes about the dress of certain colonial peoples, and investigate how disparate practices of dressing the body became intertwined in multiethnic communities.

Clothed in Dutch New Netherland: Burlington Island

In the 1620s, the Dutch government established the colony of New Netherland (Jacobs 2005:35-37). The first settlers arrived in early 1624 and began to put down roots in parts of the present-day states of New York, Delaware, Connecticut, and New Jersey. The Dutch struggled to maintain their colony. While they had established numerous social and economic relationships with local Lenape communities, they found it difficult to attract settlers to New Amsterdam, especially to southern regions of the colony (Jacobs 2005:37-38). The growth of English settlements in neighboring New England and conflict between England and the Netherlands eventually led to the end of New Netherland. Governor Peter Stuyvesant was forced to surrender New Amsterdam, which was soon renamed New York, to an English fleet in 1664.

In the late nineteenth century, a small collection of objects from the Abbott Farm site in Trenton, New Jersey, found their way to the Peabody Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Museum records indicate that these objects were excavated from the farmstead by Charles Conrad Abbott, an avocational archaeologist under the tutelage of Frederic Ward Putnam, director of the Peabody Museum. A label in the accession file, presumably written in the hand of Abbott, indicates that he excavated the material from the site of a 1668 “Dutch Trader’s House” on the south end of Burlington Island, which is located in the Delaware River.

Burlington Island had been settled by two Dutch families and eight single men in the 1620s (Veit 2002:24). This small settlement was the locus of trading in the region until Alexander d’Hinoyossia, vice-director of New Netherland, moved his family to the island in the 1650s and added more structures to the small community (Veit 2002:25-26). It was likely one of the structures of this small community that Abbott excavated in the late nineteenth century.

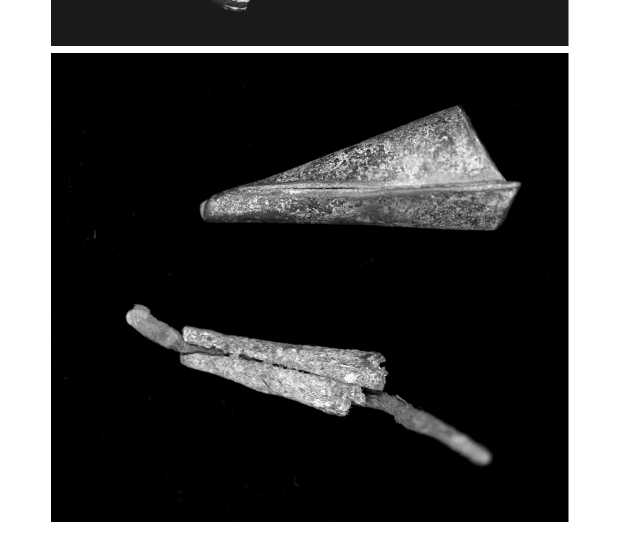

Abbott recovered artifacts of adornment from the site that included 65 assorted glass beads, two copper tinkling cones, and two hematite pendants (Figures 5.2a, b, and c). Additionally, Abbott excavated porcelain (a French term for wampum), amber, and copper beads (PM accession file 52-46). Such an assemblage of adornment items would seem to indicate Native American-style dress: glass beads and tinkling cones could be attached to clothing, wampum beads were worn as belts or jewelry, and hematite pendants would be worn around the neck in a style that was closely aligned with the dress of the Lenape people living in the region. Lenape dress was most likely more complex than such an interpretation, however. Archaeological evidence from other sites in the region suggests that Lenape people often incorporated aspects of English and Dutch clothing and adornment into their fashions because of the ready availability of many kinds of cloth (Veit 2002:106-110). Abbott’s excavation of other material from the site, including hundreds of white and red pipe fragments, wine bottles, iron nails, window glass, and clay roof tiles, led him, and later Veit and Bello

5.2a, b, and c. Artifacts of clothing and adornment recovered from the Abbott Site, Burlington Island, New Jersey. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

(1999:100, 110-115), to date the site to the mid-seventeenth century during the period of Dutch settlement.

In a recent analysis of this material, Veit and Bello (1999:98, 101-103) note that there was also a Lenape settlement on Burlington Island; the Lenape name for the island was Tinnagconc. In their discussion of the question of ethnicity in relation to these objects, Veit and Bello had trouble reconciling the items of Native American manufacture (the hematite pendants, copper beads, tinkling cones, and wampum) with European-manufactured artifacts of adornment (glass beads) recovered from the site. They wondered whether the Dutch traders living at the site were curating Native American material.

Their analysis resonates with me, not only because of the question of ethnicity, but also because of their questioning of curatorial practice. Many who interpret early colonial-period European settlements assume that Europeans held on to Native American-manufactured objects only for the sake of curiosity (perhaps as a measure of racial and social difference) and not as objects to be used in their own daily activities. The underlying assumption of such interpretations is that Native American-made objects could not have meaning in the life of someone with a European worldview. A similar assumption exists for the European-manufactured “trade goods” found at the site. It is assumed that these items were part of Europeans’ warehouse of trade goods rather than as items they could incorporate into their daily lives. When archeologists find European-manufactured items in Native American contexts (particularly glass beads in burials), they link their presence to notions of meaning. That is, researchers assume that Native peoples were eager to include the “exotic” into their worldviews. But why is this kind of interpretation so rarely forwarded when Native American-manufactured items (e. g., tinkling cones) are recovered from European contexts, especially since Native American-manufactured items are commonly recovered from colonial-period European sites in the New World?

Rothschild (2003:192) notes that the Dutch maintained a social distance from neighboring Native peoples (see also Baart 1987; Huey 1991). Dutch ministers made few attempts to Christianize local Native American populations in New Netherland, and there was little sexual contact between Dutch male settlers and Native American women (Rothschild 1996:190). Of course there were deviations from this pattern. For example, Arent Van Curler, magistrate of Albany and one of the founders of Schenectady settlement, fathered a daughter in 1652 with a Mohawk woman (Bradley 2007:93). But sexual interactions did not necessarily result in the co-mingling of material culture. Although some Native American-manufactured artifacts were recovered from Dutch homesteads in New Amsterdam, there is no indication that the inhabitants used these objects (Rothschild 2003:194; 1996:193).

Paul Huey (1988:568-570) indicates that glass beads and wampum were the most frequent items of adornment recovered from excavations at Fort Orange (in present-day Albany, New York). In addition to these items of adornment, however, black glass and brass buttons, aglets, and hooks and eyes as well as Dutch lead fabric seals were also recovered from the site. Historical accounts suggest that the Dutch often obtained items of clothing from the English; the practice was so common that a Swedish visitor to Albany in the eighteenth century remarked that while the settlers spoke Dutch and had Dutch manners, “they dressed like the English” (Shannon 1996:21). In addition, while the primary form of interaction between Dutch and Native inhabitants of New Netherland was for the purposes of trade, Dutch settlers choose to trade only for furs and food, not for household items (Huey 1988:251; Rothschild 1996:189, 193). Based on this information, we assume that Dutch people living at the house on Burlington Island never wore the items of adornment that Abbott recovered. But unlike at Fort Orange, no other items of clothing and adornment were recovered from Abbott Farm, and here we are left to wonder if it is really the case that the recovered items were not added to the clothing and adornment strategies of Dutch people living on Burlington Island.

The pattern of Dutch colonialism sketched out by Huey, Rothschild, and Veit seems to indicate that the Dutch and Lenape people kept separate residences on Burlington Island. Peabody Museum records also indicate, however, that a Lenape woman was buried at the site. Her presence has not been factored in to interpretations of the site and the artifacts recovered there. It would be easy to say that the Native American material was the result of her presence there, but what was her relationship to the Dutch men or women living there? Was this site her own home? Why was this site not interpreted as multiethnic? The answers lie in long-standing tendency of researchers to base their interpretations of the ethnicity of individuals living at a particular site on the ways that archaeologists categorize material culture: that is, since the architectural style of the house was European, then the occupants must have been European as well. This classification scheme separates people and their activities into discreet units as either “Native” or “European” But this categorization yields almost no information about the ways that individuals used material culture in processes of identity formation. Artifacts acquire symbolic meaning and value through use and activities rather than through categories that are assigned to them based on where they were produced, an interpretive bias that overlooks the possibility of multiethnic households (Jones 1997; Lightfoot 1995; Loren 2004, 2007a).

During the colonial period, mixed-blood, African, Native American, and European men and women of a variety of social and economic backgrounds created multiethnic communities throughout colonial America (e. g., Rothschild 1996, 2003; St. George 2000). So while Dutch and Native peoples often maintained separate residences in New Netherland, the context of Abbott Farm illustrates the permeability of those boundaries: a Lenape woman lived and was buried at the site, and a variety of Native American objects of adornment were recovered there. The community clearly was multiethnic and the lives of Dutch and Lenape people were intertwined—perhaps not sexually, but certainly economically and socially. These entanglements took form in daily life, including through practices of dress, where distinct cultural traditions met and reshaped social, sexual, and political interactions.

Clothed in French Louisiana: The Grand Village of the Natchez

Located along the east bank of the Mississippi River in what is now southwestern Mississippi, the Grand Village of the Natchez was occupied during the period 1682-1729 (Neitzel 1965). The Grand Village, a mound and village complex with a large central plaza, was the main ceremonial center for the tribe (Neitzel 1965). The Natchez had occupied this area of the American Southeast for several centuries before the French explored the region in the late seventeenth century (Neitzel 1965; Usner 1992).

In the early eighteenth century, the French established small households and plantations in the Natchez area; in 1729, they established Fort Rosalie there. As in many colonial situations, interactions between the French and the Natchez were fraught with violence, which culminated in the 1729 movement against the French now known as the Natchez Massacre, in which most of the French inhabitants of Fort Rosalie were killed. Ensuing violence between the French and the Natchez resulted in the dispersal of the Natchez from their homelands. Many Natchez refugees joined other tribes, including the Chickasaws, the Creeks, and the Cherokees. Today, people of Natchez descent live among the Creek and Cherokee Indians but without federal or state recognition as a Native American tribe (Barnett 2007; National Park Service 2008).

In Louisiana, it was believed that intermarriage with Native American women would foster alliances that would enable the French to survive in new terrain. Such alliances would also provide new souls ready for conversion, which was an explicit goal of French colonial projects (Hawthorne 1991; Rowland and Dunbar 1929:233; Spear 1999, 2003: 32). Through the work of Capuchin and Jesuit missionaries and some of the more pious settlers, Native peoples living in Louisiana learned about Christian notions of sin and promiscuity. Religious conversion was less than successful among the Natchez, however, as Father Gravier noted in 1708:“Monsieur de St. Cosme had not made a Single Christian among the Natche[z]” (Gravier 1708:129). Similarly, detailed descriptions written by French planter Le Page du Pratz on Natchez burial and ceremonial practices suggest that Natchez people never changed their religious and belief systems to follow Christian beliefs (Le Page du Pratz 1975).

This did not preclude numerous sexual relationships between Natchez women and French men living at Fort Rosalie (Dawdy 2006; Spear 1999, 2003:32). For example, French settler and author Antoine Simone Le Page du Pratz had a long-standing relationship with a Chitimatcha Indian woman. Like other French men in the colony, he had no problem with interracial sexual relations (Dawdy 2006:154). Did these intimate relationships as well as numerous economic, social, and diplomatic engagements between the French and the Natchez impact dress in Native American communities?

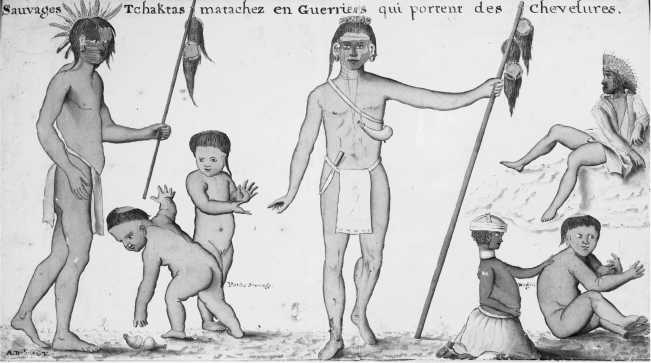

Historical images of the Natchez and many other Native peoples living in the Lower Mississippi Valley suggest otherwise; in these images Native peoples are depicted as altering their fashions only minimally. In 1734, Alexandre de Batz depicted Native American warriors wearing little else but cloth about their middle (Figure 5.3) Forty years later, Le Page du Pratz depicted a Natchez woman and her daughter in much the same way (Figure

Colonial narratives provide a bit more information and texture to our understanding of how Natchez people changed their fashions. French authors were fascinated by the ways that Natchez peoples, especially women,

5.3. Sauvages Tchaktas Matachez en Guerriers, watercolor by Alexandre De Batz, ca. 1734. Courtesy of President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 41-72-10/19.

Adorned their bodies. For example, Le Page du Pratz (1975:137) described the dress of Natchez women as exotic:

From their belts to their knees hang many strings from the same cord [ribbon] which are attached claws of birds or prey like eagles, tierce-lets, buzzards, etc., which when these girls walk make a kind of clicking, which pleases them.

Similarly, French engineer Dumont de Montigny noted that “their tresses are ordinarily laced by way of ornament with strings of blue, white, green, or black beads [made of glass]” (quoted in Swanton 1911:51). Du Pratz also described a warrior’s dress:

All the attire of a warrior consists in the ear pendants, which I have just described, in a belt ornamented with rattles—and bells when they can get them from the French (quoted in Swanton 1911:127).

The account of Father Le Petit, a Jesuit missionary, complicates our understanding of Natchez dress, however. He noted in 1730 that among the captives the Natchez spared in the massacre were a tailor and French women who knew how to sew European clothing. He wrote, “The least miserable [captives] were those who knew how to sew, because they kept them busy making shirts, dresses, etc” (Le Petit 1730:165-167). Clearly, the static visual

5.4. “A Natchez woman and girl.” From Le Page du Pratz, The History of Louisiana (1774, 37).

Images of resistance to European clothing styles that Alexandre de Batz and Le Page du Pratz offered were not completely accurate depictions of the reality of Natchez clothing styles in the eighteenth century; Natchez people wanted European-style clothing.

How does the archaeological record add to our understanding of the complexity of cultural exchange among Natchez peoples and French colonialists? Archaeological investigations at the Grand Village of the Natchez, also known as the Fatherland site, were conducted in 1930, 1962, and 1972. The most thorough studies on the site were published by Robert Neitzel (1965, 1983). Moreau Chambers excavated several burials from Mound C at the site in the 1930s, and Neitzel later published these excavations as part of the site report on his own excavations at the site in 1962 (Neitzel 1965:40-47). In the 1970s, Neitzel returned to the site to conduct excavations at several of the mounds and the large plaza area (Neitzel 1983).

Artifacts of clothing and adornment recovered from the Fatherland site’s domestic and burial contexts include shell ear pins, brass and copper tinklers, brass thimbles, Jesuit rings, religious medals, one - and two-part coat buttons, brass bells, shoe and belt buckles, and thousands of glass beads (Neitzel 1965:48-51; 1983). This variety of European-manufactured and Native American-manufactured clothing and adornment items is not surprising. Overall, the material assemblage from the site shares similarities with assemblages from other colonial sites in the region in that Native American-manufactured material was often found in combination with European-manufactured items in domestic and burial contexts. These combinations of European-manufactured and Natchez-manufactured items indicate the extent to which Natchez peoples incorporated French material culture into their lives and daily practices.

A comparison of the visual and historical records with the archaeological material recovered from the Fatherland site lays bare the limitations of some historical sources. Visual representations produced by de Batz and Le Page du Pratz fail to capture the detail and complexity of dress practices; they provide only a simplified view of the ways that Natchez people dressed. They depict them in an idealized fashion wearing more “traditional” dress: naked apart from cloth about their middle and tattoos. Neither of these depictions shows Native peoples wearing European-manufactured clothing or adornment, which we know the Natchez desired from Le Petit’s quote that they spared women and tailors in the Natchez massacre. Archaeological material challenges the accuracy of these sources, indicating that

Natchez people drew from a variety of different clothing and adornment choices available to them to construct new identities in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

The details of clothing and adornment assemblage are worth discussing here. One adult at the site (Burial 15) was buried wearing a woolen frock coat—a justaucorps much like those described at Fort Michlimackinac—as indicated by the recovery of a three-foot length of brass buttons, spanning the distance between the individual’s neck and knees. Iron coils hung from the individual’s ears, and white, blue, and black glass beads were recovered around the neck of the individual (Neitzel 1965:43). This is the only example of a Natchez individual clothed in a French-style coat at the Fatherland site. While individuals in other burials at the site were interred with various combinations of glass beads, tinkling cones, thimbles, buttons, bells, coils, religious medallions, and finger rings, no evidence remains to suggest that any other individual at the site was interred wearing an article of clothing.

Another example of a Native American individual buried wearing a frock coat is from the Bloodhound site, an eighteenth-century Tunica Indian community and cemetery located in present-day western Mississippi (Brain 1988:162-174). At the site, an adult female was buried wearing shell ear pins and a European frock coat with wide leather cuffs and large copper-covered wooden buttons. Several matching brass buttons found near the pelvis suggest that she was wearing trousers. Hundreds of small white glass beads found to the right of her head suggest that these beads were woven into her hair, a practice of hair adornment often described by eighteenth-century French authors (Brain 1988:170-171). In both of these examples, the fact that a Native American was wearing a European-made coat was an embodiment of changing identity: the coat was worn in combination with glass beads and other Native American items of adornment. The incorporation of French coats along with glass beads, rings, coils, and other items into the sartorial world of Natchez and Tunica people was strategic. It materialized power, creativity, and the ability of these peoples to incorporate both the familiar and unfamiliar in their world and on their bodies.

Another category of adornment artifacts that stands out is glass beads. Glass beads of all varieties were recovered in burial and nonburial contexts at the Grand Village (Neitzel 1965:51). The quantity and quality of beads from the site suggest that glass was an important medium for Natchez people. Historical accounts of Natchez uses of glass resonate here. For example,

Father Le Petit, the Jesuit missionary, discussed the extent to which the Natchez valued glass and placed it within their main temple building as an object of reverence (Swanton 1911:269). Moreover, eighteenth-century colonial authors seem to have been fixated by the ways that Natchez women wore glass beads around their body and in their hair in particularly lavish and sexual ways.

Glass beads found in nonburial contexts at the Grand Village include a wide variety of drawn tubular and wire-wound glass beads similar to those commonly found at mid-eighteenth century sites in the colonial Southeast. These included medium-sized blue, white, and green glass beads; polychrome beads; dark amber to black flattened spherical beads; porcelain beads; medium-red opaque, drawn, tubular white, and blue glass beads; and raspberry beads (Neitzel 1965:51; 1983:109-110). These beads were found in proximity to other items of clothing and adornment recovered from nonburial contexts: shoe buckles, buttons, tinkling cones, and iron coil earrings (Neitzel 1983:111-114).

In contrast to beads found in nonburial contexts, the majority of glass beads recovered from burials are medium-sized blue or white beads worn as necklaces. Shell beads and in fact shell artifacts in general—with the exception of one shell ear pin—are absent from the site. This absence is striking in this context as glass beads are often found in combination with shell beads in Native American sites in the colonial Eastern Woodlands. Additionally, there is little archaeological or historical evidence to suggest that Natchez people wore or made beaded clothing. Rather, their investment of labor related to beads was limited to stringing them into necklaces of distinct color combinations. In almost every instance, they wore glass beads in combination with both Native American - and European-manufactured material, suggesting the importance of glass beads in the lived experiences of Natchez peoples.

Glass beads were the materialization of the Natchez people’s intimate and economic relations with the French that had reshaped their community and sense of self. While there is no information about why the color blue was so important to the Natchez we do know that they frequently located blue beads close to the face in burial contexts. It is no coincidence that glass beads were the items that were chosen so frequently among other kinds of European-manufactured items, including other items of clothing and adornment. The properties of glass—color, sound, and translucence— were meaningful to the Natchez in the context of the ways they adorned

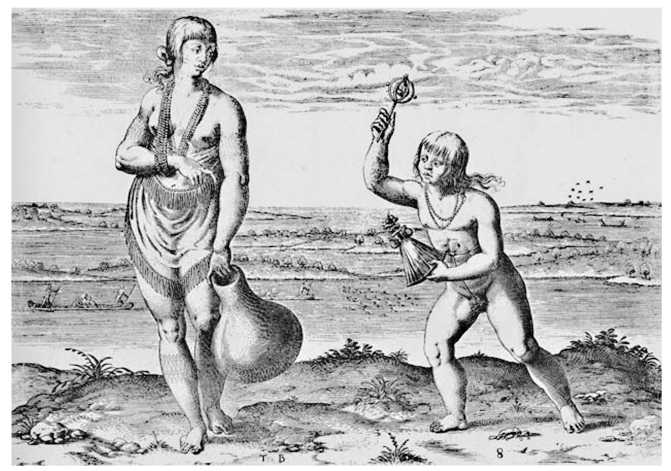

5.5. “A Chief Lady of Pomeiooc, by Theodor de Bry after John White.” Plate 8 from Theodor de Bry, America, Part 1, 1590.

Their bodies; they were placed with loved ones at the time of death, worn near the face as necklaces, and woven into hair. Turgeon (2004, 2006) argues that in many Native American communities, beads carried notions of protection and spiritual well-being in an afterlife; perhaps the same was true for the Natchez. The primacy of beads in the archaeological assemblage suggests beads were more than just simple adornment for the Natchez people. Rather, they used them to physically embody new understandings of self and the body that they created through their associations with the French.

Lindman and Tarter (2001:2) argue that “bodies are maps for reading the past through lived experience, metaphorical expression, and precepts of representation.” They place the body at the center of studies of the colonial world, where “many bodies and many interpretations of bodies were coming together in a transitional world of cultural contact, conquest, adaptation in early America” (Lindman and Tarter 2001:5; see also Loren 2007a). In this context, the measurement and classification of difference was intimately tied to the body and bodily presentation (Stoler 1997). Images such as the illustration by Theodor de Bry (after John White) in Figure 5.5 indicate such colonial concerns.

John White illustrated an Algonquian woman and her daughter wearing beads around their necks. The woman is tattooed and wears a deerskin about her waist. Her daughter is naked with the exception of a covering over her privates, but in her hand she holds a doll clothed in Elizabethan dress. The text accompanying this image reads, “They [girls] are greatly delighted with puppets, and babies [dolls] which were brought out of England.” The subtext that underlies this image is that White, de Bry, and Har-iot all believed that if properly guided and schooled, Native peoples could become civilized; that they could make themselves into the image of the English. Not an exact replica, of course, but a properly clothed and adorned facsimile.

Such imaginings of progress and sartorial order had little basis in reality in colonial America. The body is where engagements were lived, felt, experienced, and understood by every actor in the colonial world. In the context of these engagements, clothing and adornment were aspects of self that were open to negotiation and reinterpretation. Doing these tasks through dress was just one strategy European peoples and Native peoples used to understood self and other in this changing world; a process by which people from different backgrounds became “colonial” in early America (St. George 2000).

World History

World History