Between the powerful states on the western coast of South America and the Bororo culture in Brazil with its large village units there were also chiefdom societies that controlled large territorial areas but lacked the bureaucracy characteristic of a larger state. One of these chieftain cultures emerged in Venezuela in an area known as Llanos, which is north of Rio Apure and south of the Andean Mountain range with its numerous streams. It developed about 300 ce and was still in place with the arrival of the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. The extensive flooding that takes place in this area can limit farming without a strategy for water management. Canals were used in the wet season to move water away from the site and protect the plants from flooding, and then used in the dry season as irrigation channels. This was not possible without some form of centralization and control, which the chiefs were able to maintain, even though a larger state structure never developed. Nonetheless, the Spaniards, when they arrived, were impressed with the size and density of village populations. One river was said to have some 18 kilometers of irrigated fields on both sides. The crops were maize, squash, manioc, cotton, and sweet potatoes. One of these kingdoms was centered in a town defined by a roughly oval berm, which probably supported a palisade.

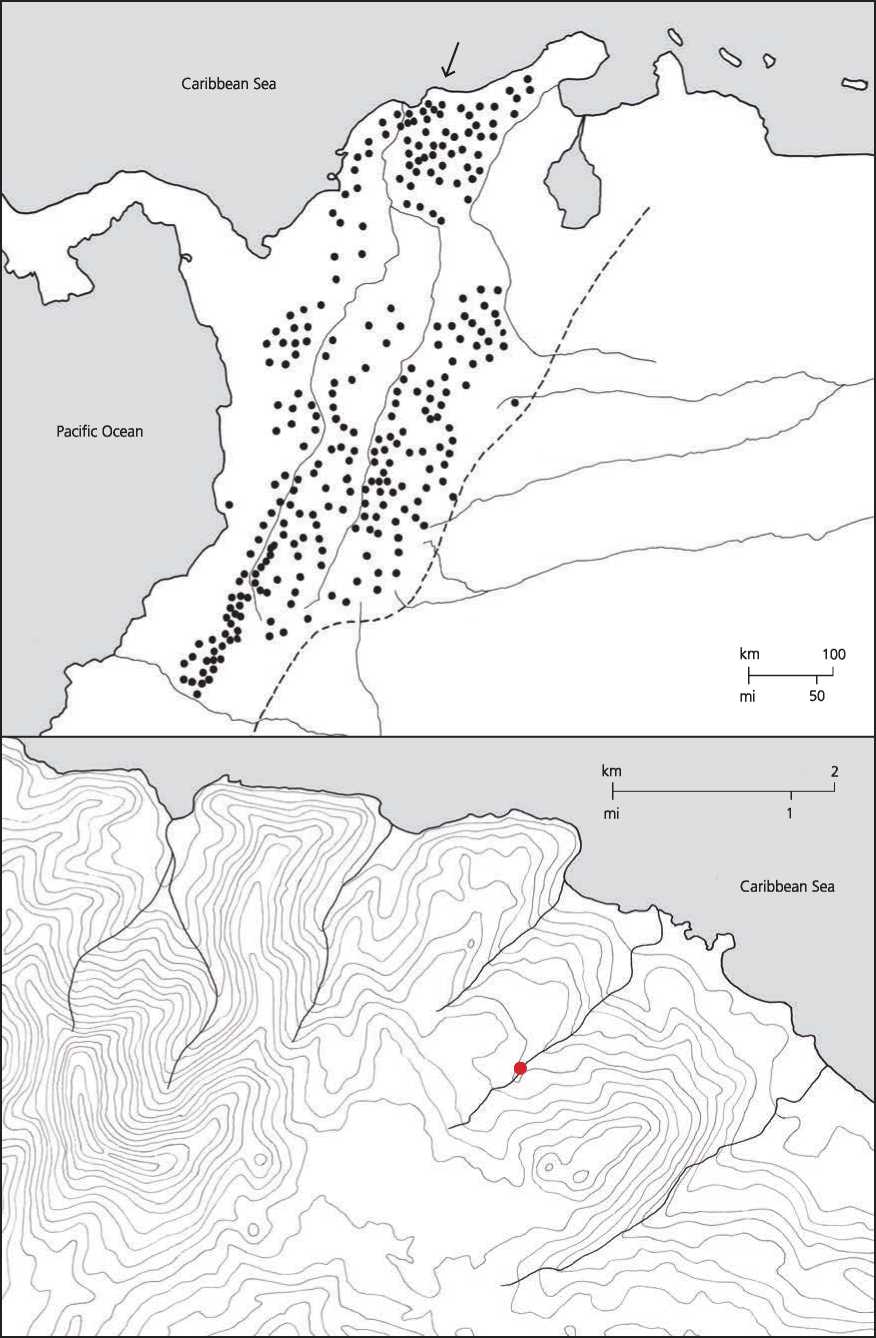

Figure 11.35: Tairona. (a) Archaeological sites from around 1000 CE; (b) location of Ciudad Pedida, Colombia settlement plan. Source: Timothy Cooke

It contained a ritual mound fronted by a wide alley defined by other smaller mounds and a row of houses. It was connected by causeways to neighboring villages. Warfare and exchange were significant features of these kingdoms as evidenced not only by the earthworks and palisades but also by the evidence of conflagrations. The ritual mound is a clear indication not only of a priestly class but also of calendric calculations typical of Central and Peruvian cultures, but not typical of cultures to the east and south in the Amazon region.29

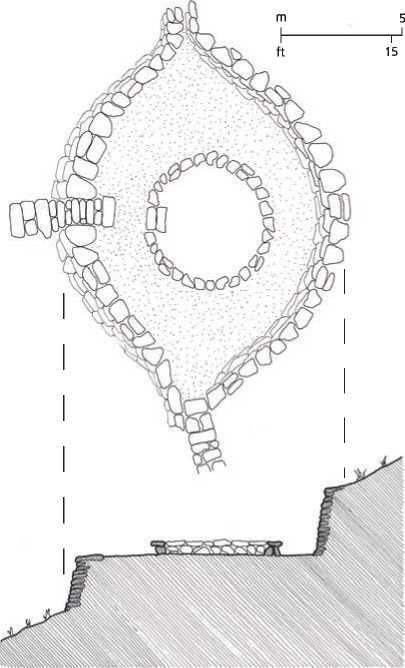

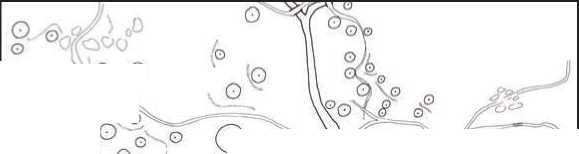

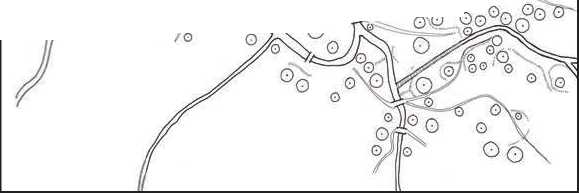

There were similar chiefdom cultures in Colombia, the totality of which are ofi:en known as the Tairona culture, though it was not a single political entity. Each chiefdom had, apart from the hierarchy of chiefs, a priestly class as well as specialists in arts and crafi:s, such as the gold workers and stone engravers. One such urban cluster was found in upper Buritaca, Colombia, along a terrace on the side of a narrow mountain valley, about half way up from the peak. Known as Ciudad Pedida, this carefully planned multi-layered town was strategically located to dominate the Buritaca River Valley. It was a very organized village, with 120 residential terraces, each with one or more circular house platforms of fine stone masonry on which the round houses were sited (Figures 11.35 and 11.36).

Figure 11.36: Gavin, Colombia. Source: Victor Englebert

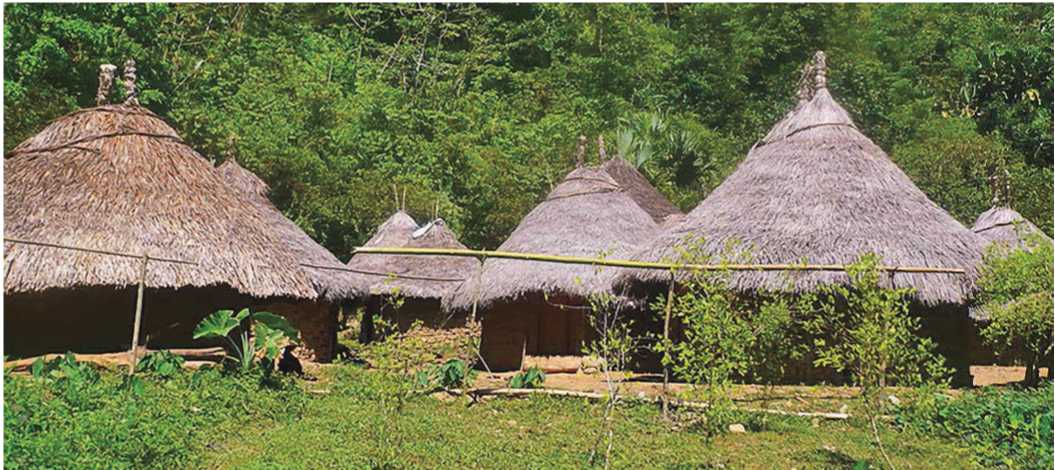

Figure 11.37: Source: Romain Breget/Http://commons. wikimedia. org/wiki/ File:Kogui_village. JPG

The terraces are interconnected by a complex web of flagstone stairs and pathways. Everything was linked by a system of water channels. If we supposed that a terrace represents a family unit, then we can assume that the populations ranged from 400 to 600 individuals. Although today the site is remote and overgrown by forest, we must imagine a difierent situation some six hundred to a thousand years ago. Not only were the slopes part of an extensive agricultural zone, but the village was connected to the outside world by means of a network of roads, the extent of which are only recently beginning to be better understood.30 The primary products exchanged from the coasts were Ash, salt, shells, cotton, tobacco, and manioc. From farther aAeld came special objects of polished stone. From the hot continental interior came coca leaves, potatoes, and sweet potato, as well as squash and corn. The Kogi people who live in the Colombia highlands still preserve aspects of Tairona culture, especially the round houses on stone platforms (Figure 11.37).

World History

World History