Between AD 900 and 1000, the junction of the Shashe and Limpopo Rivers saw a significant shift in political hierarchy within the Zhizo phase. A settlement known as Schroda was far larger than contemporary Zhizo settlements in the region and can be identified as the capital of an emerging chiefdom. This correlates with the intensification of trade links with entrepots such as Chibuene and Sofala on the southeast African coast. The Shashe/Limpopo area supported large elephant herds. Ivory and probably gold were exported where they entered complex trade networks with Swahili, Arab, and Indian centers around the Indian Ocean rim. Many of the thousands of glass trade beads at Schroda originated in Indonesia.

At AD 1000, a new ancestral Shona-speaking chiefdom entered the Shashe/Limpopo valley, wrested power from Schroda and intensified trade links with the coast (see Political Complexity, Rise of). A new and larger capital was established at K2 and the number of smaller contemporary settlements increased significantly. Increasing political power and wealth was underwritten through the control of exotic trade goods that now included cloth. This is reflected by changes in the organization of the capital, where the central cattle enclosure was moved out of the town and suggests that political power was no longer based only on cattle. James Denbow has shown that contemporary Toutswe farmers in Eastern Botswana to the west of K2 were also deeply enmeshed in trade relationships. These extended deep into the Kalahari and connected with the Okavango area of North West-ernBotswana and both pastoralists and hunter-gatherers were involved in commodity production and exchange. Despite this regional trade, however, Toutswe political hierarchies never matched those of the Shashe/Limpopo because access to exotic trade goods was limited.

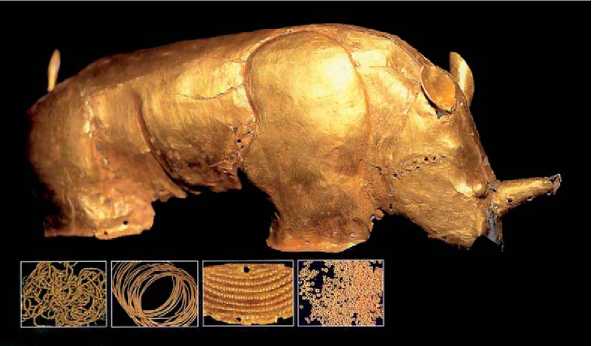

Early in the thirteenth century, K2 was abandoned and the town moved only 1 km away to Mapungubwe Hill (Figure 2). The status of elites found full expression with their occupation on top of the hill, deliberately separated from the commoner section of the town below. The establishment of the Mapungubwe state initiated the Zimbabwe Culture sequence. This represents a class-based system in which ruling elites, as sacred leaders, centralized political and ritual power, particularly rain making. Gold was assimilated into an elite value system and expressed in the thousands of gold beads, gold-plated rhino, bowl, and sceptre found in the royal cemetery on Mapungubwe Hill (Figure 3). The state extended its control into eastern Botswana though the boundaries are not yet fully established. Agricultural production was extensive, and the distribution of commoner homesteads on the edges of the Limpopo indicates that floodplain agriculture was important. The Mapungubwe State collapsed around AD 1300, possibly because of climatic and political factors. The main continuity in the Zimbabwe Culture was north of the Limpopo River with the rise of Great Zimbabwe, the capital of the Zimbabwe State that dominated much of present-day Zimbabwe.

Figure 3 The gold rhino from the royal cemetery at Mapungubwe.

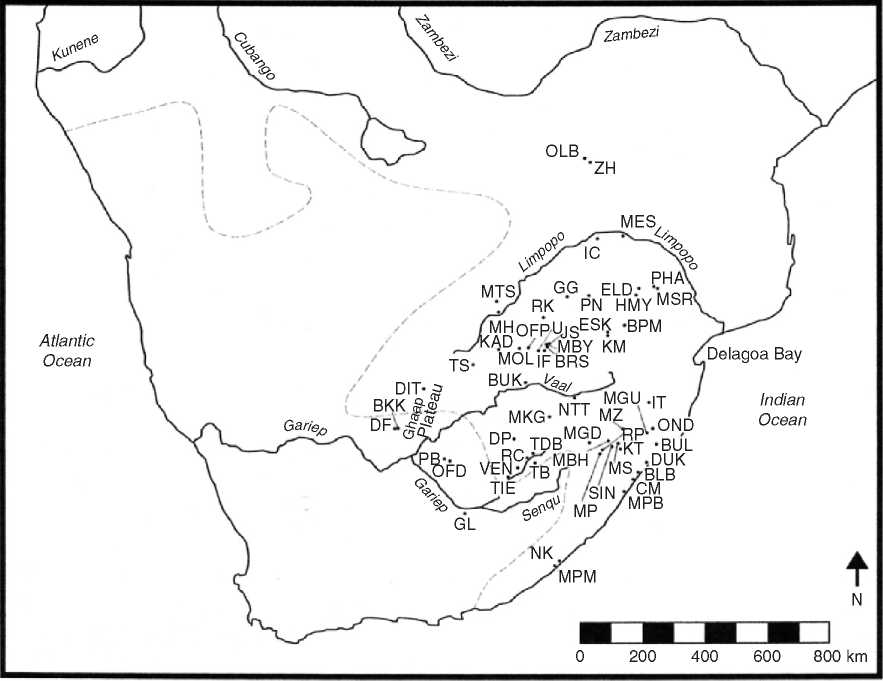

Figure 4 Distribution of Later Farmers. Taken from Mitchell P (2002) The Archaeology of Southern Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

World History

World History