All Pleistocene Californians are known as Palaeo-Indians, with a benchmark provided essentially by the appearance of the Clovis spear point: Palaeo-Indian sites are either Clovis sites or pre-Clovis sites. Pre-Clovis sites are assumed to be greater than 10 000-14 000 years old, and are inevitably the

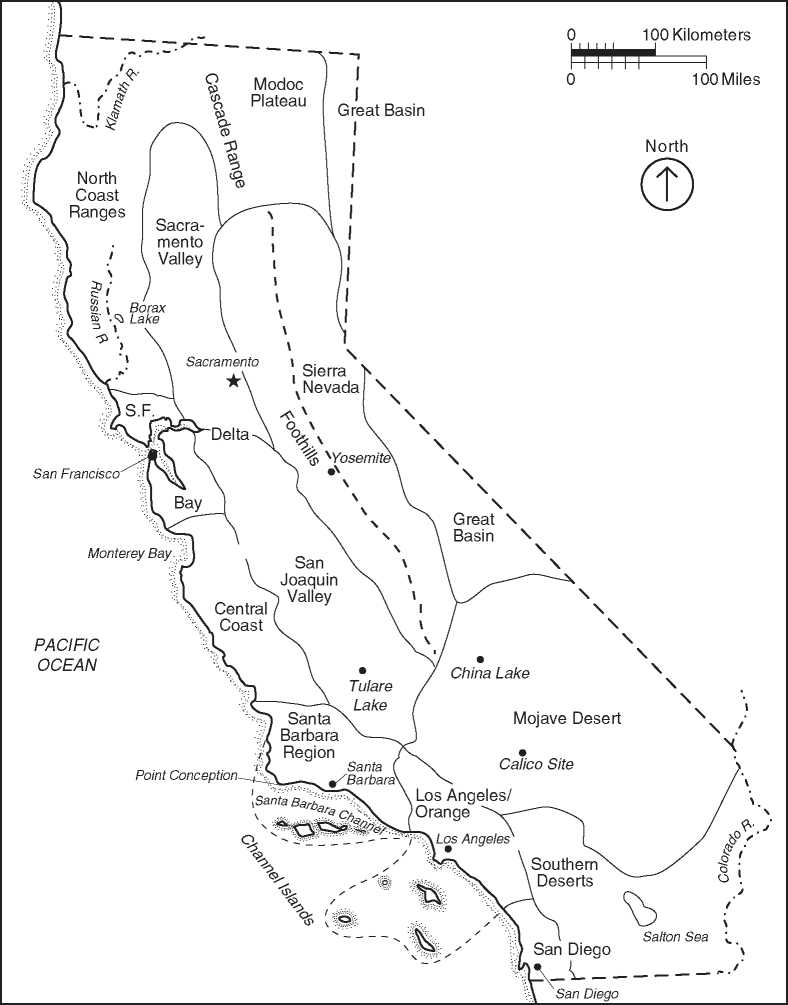

Figure 1 Regional divisions and selected California localities in California.

Subject of heated controversy. Nowhere is the controversy more apparent than at Calico, perhaps the most famous archaeological site in California. Located in the Mojave Desert, the Calico Site (Figure 1) has revealed deeply buried sediments yielding thermoluminescence and uranium/thorium dates of 135 000 and 200 000 BP, respectively, among the oldest dates ever proposed for occupation of the New World. Despite their apparent extravagance, it is not the dates themselves that are at issue. The controversy revolves around whether more than 20 000 stones recovered

From these mid-Pleistocene strata are indeed tools manufactured by humans. The overwhelming consensus among professional archaeologists today is that they are not, but instead are ‘geofacts’, rocks that were cracked and faceted by natural processes. An assemblage of undisputed stone tools has been recovered from Calico, but from substantially later deposits near the site’s surface. Most archaeologists today believe that Pre-Clovis discoveries will eventually be made in California, but almost certainly not at the Calico Site.

Less nebulous is California’s Clovis Period (c. 14 000-10 000 BP) but there is still room for controversy. Most of the evidence for Clovis comes from the shores of long-dead lakes, suggesting a distinctive lacustrine focus on the hunting of large game animals. However, archaeologists recognize that a dramatic rise in sea level over the last 10 000 years may have obscured an untold number of ancient sites along the Pacific coast, and that historical disturbances (mining, agriculture) and natural processes of erosion may have concealed or destroyed ancient sites in Valley and Foothill contexts. So it is perhaps the lack of data, or rather a bias in the data that has led to the characterization of a technologically and economically unified Ice Age in California. Moreover, problems plague many or most of the 400 Clovis points confirmed statewide. This is because the majority of Clovis points have been isolated finds, lacking in additional archaeological associations, or surface finds lacking stratigraphic context. More vexing still, the majority of Clovis points from California have been recovered by private collectors, and many points have come to the attention of archaeologists only some years after their initial collection.

Perhaps the most significant region for the study of Clovis people in California is at Tulare Lake in the southern San Joaquin Valley (Figure 1). An overwhelming majority of the Clovis points discovered in California have come from the shores and near vicinity of this extinct, ancient lake. In addition, a wide variety of stone tools have been recovered, especially scraping tools and tools presumed to be used for working wood and bone. Extinct mammal species abound, including Colombian mammoth, sloth, and Bison antiquus. In combination, Tulare Lake has a remarkable potential for study of Clovis hunting, tool manufacture and use, typology, and raw material selection. Unfortunately, nearly all of the Clovis materials at and around Tulare Lake have been churned and displaced by twentieth-century agricultural practices, and a wide majority of Clovis artifacts - including all of the points - were collected privately. To date, reports of extinct fauna in association with Clovis remains are anecdotal at best, and extensive, intact Clovis deposits have yet to be investigated by professional archaeologists from start to finish. Still, no place in California holds the promise of Tulare Lake for further understanding of Clovis people in California.

Two additional regions have yielded multiple Clovis finds: 20 fluted points have been recovered from the Borax Lake region of the North Coast Range and 15 have been reported from the shores of China Lake in the northern Mojave Desert (Figure 1). Although these finds have a better record of controlled recovery than is the rule at Tulare Lake, many are from surface contexts. These lakes also reveal Pleistocene fauna but, as at Tulare Lake, none is unambiguously associated with Clovis artifacts. So far, the ancient shores of Tulare, Borax, and China Lakes have provided by far the best window to the Clovis Period, but the view is far from clear at this time.

World History

World History