Tourism is widely recognized as the world’s largest industry. For many countries, regions, and locales, it is a major economic pillar or a promising source of revenue. Cultural anthropologists have examined tourism and tourists in terms of the consequences of tourism on a particular location, the relationship between tourism marketing and self-identity, the use of tourism to propel nationalism, ethnicity, and other identities that increase tensions or build understanding, and the relationship between tourism and development. Archaeologists have started to examine the impact of tourism on archaeological sites and the impact of tourism on the understandings of the past in order to comprehend the dynamic, recursive relationship between marketed presentations of the past and the understandings from archaeology (Figure 1).

Tourism is a bundle of cultural practices that are under constant negotiation and that are part of broader social and historical processes. Cultural anthropologists have focused on the relationships between guests and hosts to bring out the power dynamics of tourism. Embedded in tourism are concepts of leisure, wealth, and movement. There are many definitions for tourism because is it a historical, multifaceted, fragmented, and complicated set of discourses and approaches. Tourism is a practice and it is a business that includes services, transportation, hospitality, and descriptions of locales. The World Tourism Organization (WTO) differentiates tourism from activities that provide payment or long-term stays; for the WTO, tourism consists of short-term visitations that require travel, changes from one’s routine. Archaeo-tourism visits to archaeological sites and landscapes, offers two types of change, one geographic and the other temporal, by providing access to the past.

Figure 1 For tourist consumption. Representing the past for tourism, such as the wooden horse at Troy, is one of the concerns regarding marketing the past for tourism.

The broader term is heritage tourism, a term that includes visits to a locale that is themed as historic, natural, or cultural.

Archaeology is intertwined with tourism because archaeological excavations and historic monuments provide tourist sights and exhibits for display (Figure 2). On that simple level, archaeology has intersected with tourism since the Grand Tour. The Grand Tour refers to the conventions of travel, starting in the sixteenth century, by British elite crossing the Channel to Europe and south to the Mediterranean. The Grand Tour was educational in character; young men, and occasionally young women, gained social polish by traveling to the sites of Classical Antiquity. A primary goal of the seventeenth-century Grand Tour was Italy, where the children of the elite, aspiring political leaders and young writers and artists, went to experience first-hand the ruins of Classical culture. At its height in the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Grand Tour continued to Greece. By the nineteenth century, voyages continued to the Holy Land and the ancient splendors of Egypt. As archaeology expanded and transportation became more readily available, travelers became tourists and visits to excavated sites allowed tourists to claim education as a feature of their travels.

With travelers and tourists visiting archaeological sites, directors of large-scale projects have invited participation in digging. The current incarnations include dig for a day, an approach that makes excavations into a tourist experience. Whether tourists are excavating or photographing sites, the popularity of

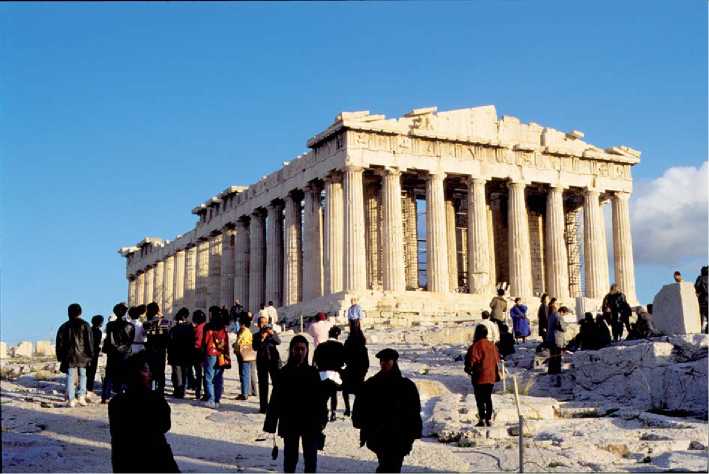

Figure 2 Tourists at a site. Tourists at the Pantheon: the popularity of archaeological sites, due to tourism, raises apprehension over preservation.

Sites can endanger fragile remains because heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing components of global tourism (see Popular Culture and Archaeology; Who Owns the Past?).

Heritage tourism has become a key concern for archaeology. Some professionals envision an accelerating partnership between archaeology and tourism; tourists provide financial resources for revealing and preserving material remains from the past and archaeology can be an interpretive vehicle for discovering the past of a specific, marketed location. The success of tourism highlighting archaeology means that tourist sites constitute some of the most famous archaeological sites (to invoke just a few renowned examples, Machu Picchu, Masada, the Pyramids at Giza, Mesa Verde, Stonehenge, the Pantheon, the Great Wall of China). Tourist resources facilitate conservation and presentation of sites, although rarely without controversy. Controversy grows out of new understandings of archaeological and historic resources, in heritage tourism, as capital to be exploited in a rational manner. The archaeological record, rather than a resource for scholarship, becomes an economic value for a community or a government. The success of an archaeological site, under this framework of significance, does not depend only on the finds and their presentation but also on the vagaries of the tourist market and to concerns over what will be popular for tourists.

As a neoliberal approach to archaeological sites, heritage tourism encourages particular ways of knowing the past and material culture that situate the appropriate uses of the archaeological record, uses that might be at odds with the profession. And as heritage sites move beyond their historic and/or emotive value and constitute economic value for the tourist market, they can become sites for violence. Archaeological sites and historic monuments have become targets of aggression, both from nationalist fervor and during wars. The spectacular examples include the destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, India

(1992) , the Mostar Bridge in Bosnia-Herzegovina

(1993) , and the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan (2001) as well as the attack on tourists visiting the Hatshepsut Temple in Luxor, Egypt (1997). The danger of violent attacks on historic monuments because of their symbolic value, the menace of popularity endangering fragile, and even sturdy, features, and the value of antiquities leading to the looting of artifacts are major growing concerns for the profession.

Interactions with the tourist industry and national government are facets of the intersection of archaeology and tourism. Contemporary ethics encourage archaeologists to work with local and descendant communities, usually referred to as stakeholders.

Acknowledging the politics of archaeology opens up the ownership of the past, particularly the past as presented to the mass audience. One of the key examples is Masada, a Roman period fortress in Israel. Excavated as a nationalist endeavor, Masada is a famous archaeological site, renowned for the heroic story of Jewish rebels against the Roman Empire committing suicide rather than submitting to slavery and for its dramatic vistas near the Dead Sea. The 1960s excavations brought attention to the material remains on the plateau and the popularity of the site has brought the architecture and artifacts to mass audiences. The marketing of Masada encourages those who wish to see the historic story; tourism creates expectations that archaeology will shed definitive light on the past. Those expectations have led to scholars raising questions about the accuracy of the current interpretations. The challenge comes from the tourist industry being a stakeholder that promotes more tourists to see the site with interpretations for the tourist sight. For archaeology, this raises questions over the appropriate analysis of the material remains. As tourism continues its growth trajectory, archaeologists face the paradox of the tourist industry, as new stakeholders, demanding more materials and particular interpretations from the archaeological record.

At sites that have integrated archaeology into their research project for public consumption, like Colonial Williamsburg, there are concerns regarding authenticity. Interestingly, accuracy is the enticement contested in heritage tourism. Even at theme parks, places of the imagination like the Holy Land Experience in Orlando, Florida, the goal is accuracy in material details. Archaeology is seen as a tool providing objects, imagery, and authority; the tourist industry provides the representations of the materials. Archaeologists, because of the many in the profession whose work is being intertwined with archaeo-tourism and heritage tourism, are critically examining the implications of archaeological actions within the parameters influenced by the new set of possibilities and paradoxes.

These dynamics are encouraging archaeologists to engage in participant observation on the impact of the tourist industry. Methods to bring out the complexities of the paradoxes involved in heritage tourism include the examination of the legal framework for UNESCO’s World Heritage List and exploration of government policies that stress particular aspects of the cultural landscape for tourism. Tourist advertising, souvenirs in gift shops, and the layout of signs and visitors’ centers illustrate the conundrums of representation. Ethnographic interviews with visitors, designers of historic parks, and owners of history theme parks

Bring out the contingencies of decision making. Such studies find local-level responses and negotiations that come with asymmetrical interrelations. With globalization, similar forces are influencing the implementation of conservation, preservation, and presentation of the archaeological past. With local responses and decisions varying greatly, the intersection of archaeology and tourism requires sustained exploration and research.

See also: Ethical Issues and Responsibilities; Popular Culture and Archaeology; Who Owns the Past?; World Heritage Sites, Types and Laws.

World History

World History