Modern urban dwellers are cushioned, to an extent, from the rhythm of the seasons, from the immediate effects of good or poor harvests and of the health and fertility of flocks and herds. But in any pre-industrial and essentially rural society, the association of communities with the natural environment and their dependence on it are both close and direct. The world of the Celts was no exception. The single farm or small nucleated settlement was the home of many Celtic peoples, and even the large communal centres, like Danebury in Hampshire or Bibracte in Burgundy, were not so very far removed from the surrounding countryside.

For the Celts, the effect of this constant interaction with nature manifested itself in many ways. The pre-Roman Celtic artist, who expressed himself mainly, though not exclusively, through the medium of metalwork, chose as his themes the plants and animals by which he was surrounded in his daily life. Anthropomorphic representation was of less interest to the Celtic metalworker. Sometimes the foliate and zoomorphic designs depicted were fantastic, unreal and full of imagination, but these fantasies do not conceal the fact that the artist had a deep understanding of his subjects. The bronzesmith and blacksmith appreciated, indeed revered, the beauty and the elegance of animals and the sinuous curves of foliage, and, by exaggerating some of their features, enhanced and promoted their aesthetic qualities.

The natural world of the Celts is nowhere manifested more clearly than in the realms of religion, ritual and myth. For the Celts, the supernatural forces perceived in all natural phenomena could not be ignored but had to be appeased, propitiated and cajoled. In Celtic religion, it was the miraculous power of nature which underpinned all beliefs and religious practices. Thus, some of the most important divinities were those of the sun, thunder, fertility and water. These were the pan-Celtic deities: the celestial gods, the mother-goddesses and the cults of water and of trees transcended tribal boundaries and were venerated in some form throughout Celtic Europe. Every tree, mountain, rock and spring possessed its own spirit or numen.

The divine sun was represented by the symbol of the spoked wheel as early as the later Bronze Age: in pre-Roman and Romano-Celtic Europe, the solar force was manifest as an anthropomorphic divinity who none the less retained his original wheel motif to represent the moving sun in the sky. The spirit of the sun was capable of creating and destroying life: it could fertilize or shrivel the crop in the ground; it was a promoter of healing and regeneration, and was even able to light the dark places of the underworld. Water was acknowledged as a powerful force, again from early in European prehistory. For the Celts, the numina of rivers, marshes, lakes and springs were potent supernatural beings who, like the sun, could both foster and destroy living things. Water was perceived as mysterious: it falls from the sky and fertilizes the land; springs well up from deep underground and are sometimes hot, with therapeutic mineral properties; rivers move, apparently with independent life; bogs are capricious, seemingly innocuous but treacherous. All these aquatic forces were venerated, propitiated and given offerings. In the Romano-Celtic period huge, wealthy cult establishments grew up around curative springs presided over by such divinities as Sulis at Bath in Britain and Sequana near Dijon in Gaul.

Single trees, woods and groves were sacred. Before the historical Celtic period, open-air sanctuaries, like the sixth-century BC Goloring enclosure in Germany, had as their cult focus a sacred post or living tree. This tradition was maintained by communities all over Celtic Europe, from the fourth century BC until (and indeed beyond) the end of official paganism in the fourth century AD. Thus, at the third-century BC ritual enclosure of Libenice in Czechoslovakia, there were sacred wooden pillars or trees that had been adorned with great bronze torcs or neckrings as if they were cult statues. At the opposite corner of the Celtic world, the late Iron Age shrine of Hayling Island in Hampshire was built around a central pit holding a post or stone. The Romano-Celtic sanctuary of the Mother-Goddesses at Pesch in Germany had a great tree as a cult focus. At Bliesbruck in the Moselle, numerous sacred pits were filled with votive offerings which included the bodies of animals and tree-trunks. Romano-Celtic iconography emphasizes the importance of trees in cult expression: altars to the Rhineland Mothers and the sky-god are decorated with tree symbols. The groups of public monuments known as 'Jupiter-Giant Columns' were composed, in part, of tall pillars carved to represent trees. The ancient Roman writer Pliny refers to the sacred oak of the Druids. Epigraphy alludes to Pyrenean deities called Fagus (Beech-Tree) and 'the God Six-Trees'. The sanctity of trees seems to have been based on their height, with their great branches appearing to touch the heavens; their longevity; and the penetration of their roots deep underground. They thus formed a link between the sky, earth and underworld. In addition, trees reflected the cycle of the seasons, with the 'death' of the deciduous tree in winter and its miraculous 'rebirth' with the burgeoning of new leaf-growth in the spring. The Tree of Life allegory was perhaps enhanced by the fact that animals use trees both for shelter and for food.

The sanctity of natural phenomena and of all elements of the landscape led inevitably to the veneration of the animals dwelling within that landscape. Accordingly, wild and domesticated species were the subject of elaborate rituals and the centre of profound belief-systems. The Celts depended on domestic beasts for their livelihood, on wild creatures for hunting and on horses for warfare. This intimate relationship between human and animal in so-called secular life stimulated the concept of beasts as sacred and numinous, whether in possession of divine status in their own right or simply acting as mediators between the gods and humankind. Animals were sacrificed in rituals which sometimes involved eating all or part of the carcase but, on other occasions, the animal was very deliberately left unconsumed, as an unsullied gift to the supernatural powers who had provided humans with these beasts and who demanded offerings which meant a very real loss to the community. The sacrifice of animals must have represented more than simple offerings of valuable commodities. Examination of the evidence for religion in the Romano-Celtic period, when images and epigraphy present us with clues as to how the divine world was perceived, shows us a whole range of deities whose names, cults and

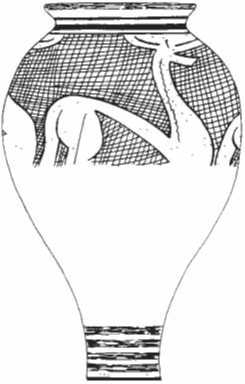

Figure 1.1 Iron Age pot with deer motif, Roanne, Loire, France. Paul Jenkins,

After Meniel.

Identities were intimately associated with, and indeed dependent upon, the animals depicted with them. This intimacy reached its peak in the perception of gods in human form taking on the features of the beasts themselves - hooves, horns and antlers. Moreover, sacred animals could be envisaged and depicted not only as the normal creatures recognizable within the everyday world but also as fantastic beasts whose multiple horns or composite form remind us, indeed, of the weird and wonderful creatures of the Book of Revelation: 'and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns. . .' (Revelation 12.3).

A major theme which is explored in this book is the close link between the sacred and the mundane. It is quite impossible to separate the profane and spirit worlds, or the ritual from the secular aspects of society. Such a division is spurious and should not be attempted. It is certain that ritual pervaded most, if not all, aspects of life and was confined neither to specific ceremonies nor to formalized religious structures. The association between humans and animals expresses very clearly the conflation of cult and the everyday: the killing of animals, whether for food or for sport, had a ritual aspect; warfare was closely bound up with ceremony and religion; for the Celtic artist symbolism, sometimes overt religious symbolism, was central to his repertoire. The vernacular sources, too, show us a world where heroes straddle the realms of the mundane and the supernatural, where animals can speak to people and where divine beings can change at will between human and animal forms. These early Celtic documents open a door on a world of shifting realities and ambiguities, where animals interact closely with both humankind and the gods. To the Celts, animals were special and central to all aspects of their world.

World History

World History