We feel that demography lies at the heart of the late arrival of humans to the New World. Simply said, there could be little or no population expansion if there was little or no population growth. Instead of a possible expansion rate of, say, 30 km (20 miles) per generation of hunters, there would be no need for expansion if the number of hunters did not exceed the holding capacity of a given region. To expand, carnivore predation of humans or their food supply had to be reduced. A 1918 comment referred to by David Quammen (2003:38) reinforces one restricting factor in a “barrier” hypothesis, namely, child-napping, which would have contributed to the limiting of human population size in late Pleistocene Siberia:

Careless mothers leave children unattended [remarked R. G. Burton in 1918] and a panther [leopard], skulking around the village outskirts after dark, even though not a confirmed man-eater, will always be ready to carry off a child if no one is watching.

Such a viewpoint fits well with Quammen’s (2003:70) discussion of carnivore food size preferences and restrictions. Prey determination is based on what size animal a predator can kill and swallow. These restrictions apply to the solitary predators, but upper size

Fig. 4.7 Inasmuch as shamanism was present throughout the New World, the practice must have been part of the late Pleistocene Paleo-Indian culture brought fTom Siberia. Some of the bone objects found at Mal’ta and Ust-Kova may have been used by shamans. Shown is a shaman doll, ca. 60 cm high, on sale at the Irkutsk Regional Museum gift shop (CGT color 10-1-00:29).

Limit can easily be extended for the social predators - hyenas and wolves - whose effective mass is multiplied by pack size. The hyena’s bone-crushing jaws and teeth circumvent the swallowing restriction of other carnivores.

While Pleistocene cave lions and bears must have been terrifying - for example, the menacing 30 000-year-old paintings of them in Chauvet Cave, France (Clottes 2003) - we wonder whether carnivore horror may not have been even greater for the killing packs of night-prowling cave hyenas and wolves. The unattended toddler would make a nice, easily snatched evening meal. Many animals are depicted in the cave and mobile art of the European Upper Paleolithic mammoth or Arctic steppe fauna: lion, feline forms, bear, rhinoceros, red deer, hind, chamois, horse, muskox, ibex, goat-sheep, reindeer, wolf, hare, megaloceros, mammoth, bison, auroch, and many others, including salmon, sole, other fish, seals, and birds, such as owls, and even a grasshopper (Leroi-Gourhan 1967). While we have failed to find any hyena portrayal in our literature search, Guthrie (2005:236-267) has done so. According to this eminent zoologist, whose book on Paleolithic art shows scores of mammals he identifies, he found depictions of hyenas to be very rare. He proposes only two possible hyena depictions. Keep in mind that Guthrie is a zoologist, not an art historian. Hence, his identifications carry considerable credibility. One image of a hyena was found at La Marche, France. However, there are no spots indicated as is the case of the second depiction, found at Parpallo, Spain. The Spanish scene shows a smaller animal attacking a larger and horned mammal. The attacking creature seems to be clenched to the throat of the prey. Guthrie suggests that the predator is a hyena because of the erect short tail and the spotted coat. With the bones and teeth of hyenas so abundant in the Paleolithic, one wonders what was the reason for the rarity of hyena depictions. Other Upper Paleolithic predators are rather commonly depicted. Fear and revulsion come quickly to mind, as discussed in our section on living hyenas. Anderson (1984:60) also finds “that there are few representations of the spotted hyena in Paleolithic art, [but there is] an ivory sculpture fTom La Madeleine.”

Does this rarity of hyena images mean that cave hyenas were so unimportant that they did not merit depicting? Or were they so horrifying that it was too dangerous to portray them, even in the deep, dark sanctuaries of European limestone caves? Vereschagin and Baryshinkov (1984:496) noted that large amounts of cave hyena remains have been found in numerous European cave sites. Gary J. Galbreath (personal communication, September 14, 2007) also related that large numbers of hyenas have been found all over Europe, adding that “the individuals were quite large by modern hyena standards.” Thus, there are a variety of reasons to be suspicious about the role hyenas might have played in Siberian late Pleistocene human demography. After all, carnivores and humans were competing for the same food and shelter resources.

There is another possible limiting factor for human population size in Siberia - human sacrifice to persistent and troublesome predators. Citing the 1925 edition of the 1825 writings of the self-educated Russian naturalist of Primorsky Territory and Manchuria, N. A. Baikov, Quammen (2003:356) related that an infant might be tied to a tree as a sacrifice to an aggressive marauding Amur tiger.

While hyenas and humans seem to have been strongly competitive associates in southern Siberia, one wonders if that association was maintained as Upper Paleolithic

Siberian people pushed further north toward Beringia in the late Pleistocene. Ovodov’s finding of cave hyena remains and stone artifacts in Geographic Society Cave demonstrates that the association existed even as far east as the Sea of Japan. If eastern Siberian Upper Paleolithic people used the Amurian-Pacific continental shelf as a route to Beringia, one might expect the hyena-human relationship to continue beyond the 55° N limit because of the warming effect the Pacific Ocean would have had on the continental shelf. However, the association seems to have ceased before humans reached Alaska. Kurten and Anderson (1980:198) report that bone-eating hyenids had reached North America, although their fossils are rare, and none has been identified as a cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea).

There are no known depictions of hyenas in Siberian rock or mobile art, even though images have been identified which are attributable to late Pleistocene-early Holocene fauna (Jacobson 2005:121). Jacobson notes that one Altai image can be confidently identified as having a Pleistocene age, namely that of a wooly rhinoceros.

In sum, we envision a diminishing food supply and shelter availability as one proceeds northward in Siberia. At some point the competition between humans and hyenas (and other carnivores) must have so intensified that the latter preyed on humans with increased frequency. The human groups were reduced in number to a level of bare survival. As the food resources diminished or became harder to come by with increased latitude, there must have been a zone in which we suggest the competition was so intense that humans were unable to proceed northward. At the same time, hyena groups were unable to expand due to the same limited food supply that both species competed for. We propose that the competitive struggle climaxed at 55-56° N, the northern limit of known hyena remains, and about the northern limit of dated late Pleistocene archaeological sites.

While climate may be the sole or main controlling factor for the northern limit of human occupation, as revealed by their archaeological residue in Siberia, we feel otherwise. The northern limit of Pleistocene hyenas seems to have been about 55-56° N. With one exception, Kuzmin (1994; see also Kuzmin and Tankersley 1996) lists no early Upper Paleolithic (39 000-24 000 BP) sites above 55° N. Kuzmin does list a number of archaeological sites north of 55° in latest Upper Paleolithic times (24 000-10 000 BP). One example is Ust-Kova at 58° N. The deepest cultural layer produced a radiocarbon date, based on charcoal, of 14 000 BP. Despite the recovery of a large faunal assemblage, there was very little carnivore damage and no direct or indirect evidence of hyenas at Ust-Kova.

It would be foohsh on our part to over-emphasize the potential contribution of hyenas to the late human colonization of Beringia, but we want the reader to consider the possibility of such an additional inhibitor to the late peopling of the Americas relative to the spread of modern humans everywhere else in the world, except deep pelagic Oceania.

The reader may also be wondering how a study of perimortem bone damage could wind up with discussions of dogs, clothing, cults, shamans, missing burials, and human teeth. To our way of thinking the bone damage can be readily described, but for fuller understanding it has to be put into some sort of cultural, temporal, populational, and environmental context. This context involves issues that came up in the course of our data collection.

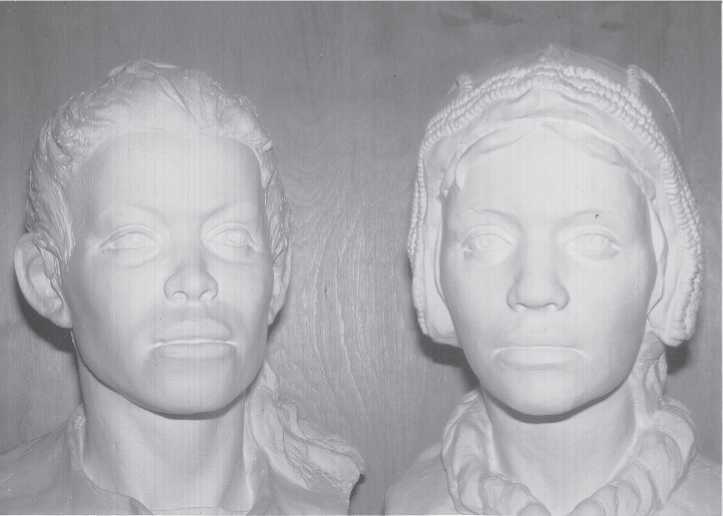

Fig. 4.8 Facial reconstructions by M. M. Gerasimov of the Sunghir sub-adults. Their prognathism follows from the fact that they had large teeth. Although large, they were simplified and morphologically like teeth of modern Europeans. These reconstructions are the best ever made, showing what Cro-Magnons looked like. Given their dental similarity to that of the Mal’ta child, had he or she lived to a comparable age, they would likely have looked similar to the Sunghir pair (CGT color LPR 1-6-81:19).

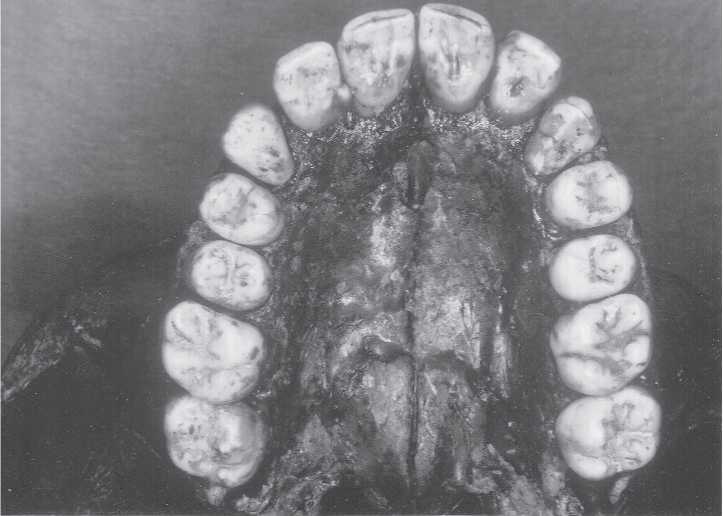

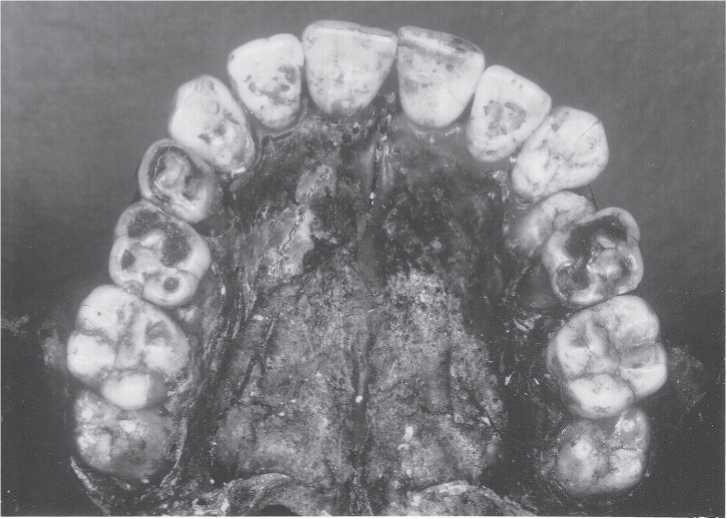

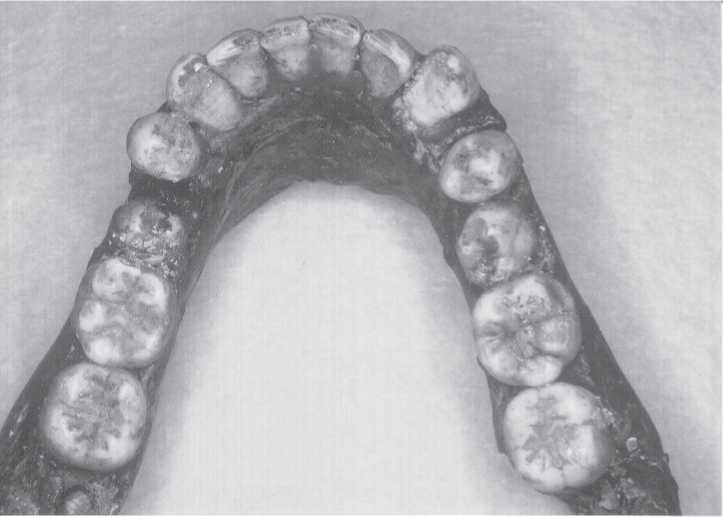

This context showed that hyenas were a significant part of the southern Siberian landscape, perhaps so much so that they contributed to the limiting of the Mousterian hold on Siberia, allowing the entry and expansion of bands of European Cro-Magnon people to as far east as Lake Baikal (Mal’ta). Upper Paleolithic burials in European Russia, such as Sunghir (Figs. 4.8-4.12), are dentally very much like modern Europeans and Mal’ta. A second prong of modern humans entered far eastern Siberia. These East Asians were dentally very unlike the Europeans. Called Sinodonts, these anatomically modern humans reached the New World, whereas the Cro-Magnons and the Siberian Mousterians did not.

The human and animal figurines found at Mal’ta and Ust-Kova, both open sites evidencing butchering of many hunted animals, proclaim much more symbolic activity than the inhabitants at earlier sites such as Denisova and Okladnikov caves.

However, the marked differences in carnivore bone damage between the earlier and later assemblages strongly suggest that carnivores were less of a threat in later than in earlier sites. Perhaps 20 wolves prowling at night about the Mal’ta and Ust-Kova camp fires would have been less of a terror than 20 larger cave hyenas (Fig. 4.13).

A great deal of government-funded archaeological excavation has taken place in Siberian late Pleistocene sites. The first discovery of Siberian Paleolithic stone tools

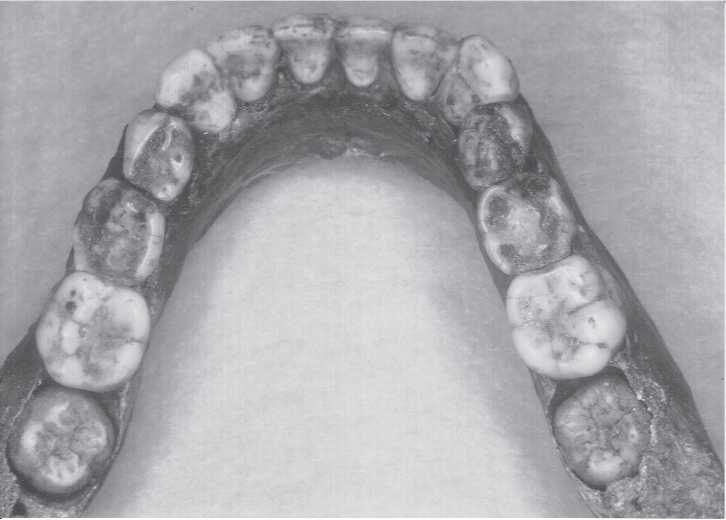

Fig. 4.9 Maxillary teeth, Sunghir A (12-15-year-old male). Like modem Europeans, Sunghir A has weak central incisor shoveling, no double-shoveling, a reduced breadth of the lateral incisors, strong expression ofCarabelili’s trait on the first molar, no cusp 5 on the first molars, no first molar enamel extension, and other similarities. These features are also found in the Mal’ta child (Fig. 3.82) (CGT color LPR 12-25-80:1).

Fig. 4.10 Maxillary teeth, Sunghir B (9-10-year-old female?). The same comments on the dental morphology of Sunghir A also apply here (CGT color LPR 12-25-80:5).

Fig. 4.11 Mandibular teeth of Sunghir A. Most notable, and like modem Europeans, is the absence of the protostylid and cusps 6 and 7 on the first molars, and lack of cusp 5 on the second molars. These features are also found in the Mal’ta child (Fig. 3.83) (CGT color LPR 12-25-80:4).

Fig. 4.12 Mandibular teeth of Sunghir B. The same comments apply as on the dental morphology of Sunghir A (CGT color LPR 12-25-80:7).

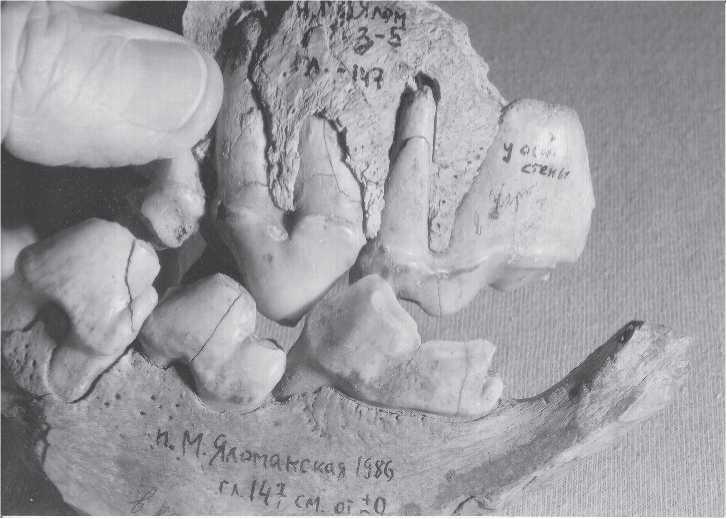

Fig. 4.13 Hyena jaw fragments from Maly Yaloman Cave (1986). We conclude our illustrations with this

Photograph to make the point that it was the large quantity of perimortem bone damage caused by carnivores that enabled us to propose that this Altai cave site, as well as Okladnikov Cave, despite their stone artifacts, were used as much by carnivores as by humans. For example, 48% of the Maly Yaloman bone assemblage had hyena stomach-acid erosion, and the amount of carnivore bone damage at Maly Yaloman was equal to that found in the Razboinich’ya hyena cave. As we came to realize, hyenas must have been a major feature of the Siberian landscape, so much so that we envision them as having contributed significantly to the late human colonization of the New World, and contributing to the discontinuous occupation of Siberian regions, which allowed nomadic Upper Paleolithic Europeans to replace the Siberian Mousterian Neanderthals (CGT neg. IAE 8-5-03:35).

Occurred in 1871 in Irkutsk, at what is now called the Military Hospital site. Since then the recovery of Paleolithic remains from cave and open sites easily totals in the tens of thousands of stone artifacts, cores, debitage, and several bone artifacts, including human figurines, carvings of waterfowl, scratched drawings of mammoth, unique dog and fox burials, etc. In contrast, the number of human bones and teeth that have been recovered is disproportionately (and disappointingly) small.

A combination of technology, dog domestication, climate and vegetation change, megafaunal and hyena extinctions, and the arrival of anatomically modern human Sinodonts from Northeast Asia were all necessary elements for explaining the late colonization of the Americas. We emphasize the competitive role that hyenas may have played in the lives of late Pleistocene Siberians.

At a drizzly late night vodka-fueled field campfire discussion, one of our 20 or so Russian colleagues replied, after being asked why the New World was colonized so late:

“Why would anyone want to leave the paradise of southern Siberia?” Our bone damage study cannot answer that question, but it does offer a scenario of why the colonization was so late in human migratory history. Natural selection molded our species to explore. We are now robotically searching out our distant neighboring planet, Mars. If we should discover bones, Nicolai, Olga, and I will stand ready to help.

World History

World History