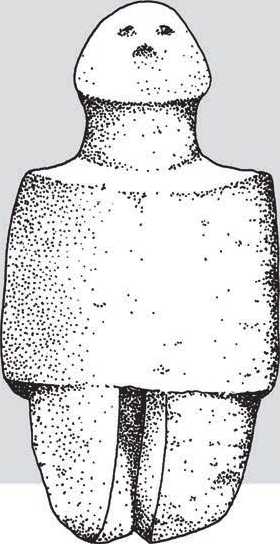

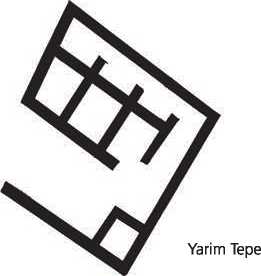

The shift: from the shaman to ritual specialist is difficult to detect in the archaeological record, but that it occurred in many of these villages around this time seems quite apparent. Shamans are traditionally focused on curing and prophecy. They act as intermediaries between the realm of the living and the realm of the dead. Their art lies in their knowledge of plants and animal spirits. Ritual specialists, on the other hand, probably inherit their power or derive it from the codified knowledge necessary to conduct public rites for the benefit of a community or individual. These rites are calendric, and performed in conjunction with the agricultural cycles. A ritual specialist will also be associated with a particular site and building. Historically, the transition is not necessarily where one replaces the other. Among the Navajo, shamans and priests co-exist. However, in the Anatolian/Levant area, household rituals had become quite pronounced and it was from within this context, enhanced by bull rituals, that ceremonial life in Mesopotamia slowly grew in scale. Only with the establishment of proto-urban towns in Mesopotamia do we find the unambiguous evidence for the distinctive pattern of town and temple that was to become characteristic for later Mesopotamian culture. Evidence for the transition is at Tell Gawra, which came to have a structure that can be identified as a temple around 3500 bce. Before then, apart from the great ritual center of Gobekli Tepe, the house shrine—and the emerging ritual centers of the herders—remained the dominant mode of religion, even though it was only a matter of time for the house shrine to rise to the level of an autonomous institution. Throughout this period we continue, therefore, to see animal figurines and mother goddess figurines at almost every site, but some seem to be given special value (Figure 8.19a, 8.19b). One such statue, at ’Ain Ghazal, was located on a rise at the outskirts of the village. It was placed at the end of a stone path specially made for it. The sculpture was probably displayed on a small platform of reeds or wood at the end of the path. Could the figure have evoked a primeval deity like Nammu, the later Sumerian deity who represents the creator of mankind? Could it have been part of a birth cult? 14

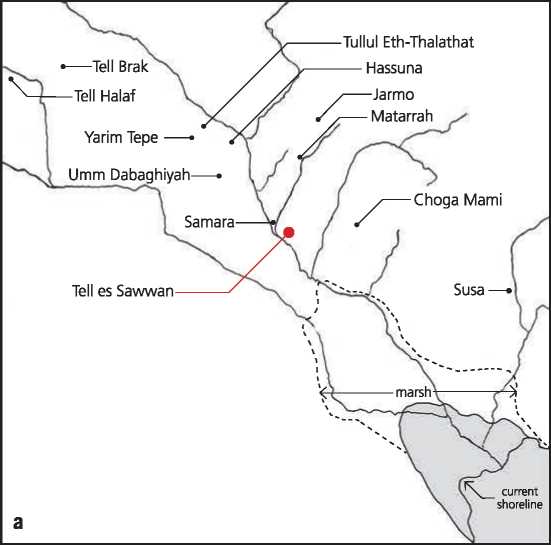

In Tell es-Sawwan, we see an example of the autonomous shrine in the houses closest to the river that had under their floors and in their vicinity up to four hundred burials, many of which were children’s burials. Graves were mostly ovals filled with yellow sand, leveled, and plastered over with a layer of gypsum or occasionally with bitumen. These graves were secondary burials into which the bones had been transferred after first having been buried elsewhere. One building seems to have been particularly important. A suite of four rooms on one of its flanks was connected by axially arranged doorways and probably served as a mother goddess shrine. Not only were numerous burials found under the floors of these rooms, but a small altar niche with a figurine was found in the last room. In the room before it, traces of burnt ofi'erings were discovered that included gazelle, sheep, and goat bones. Since this cult center was close to the river, the location may have been viewed as a sacred threshold.15

Figure 8.19a, b: Figurines: (a) Cyprus, (b) Bouqras, Syria. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Cyprus Anthropological Museum and Ackerman

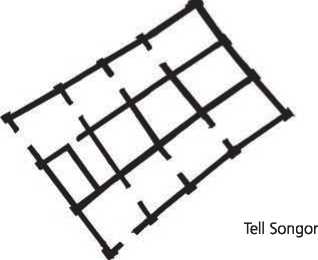

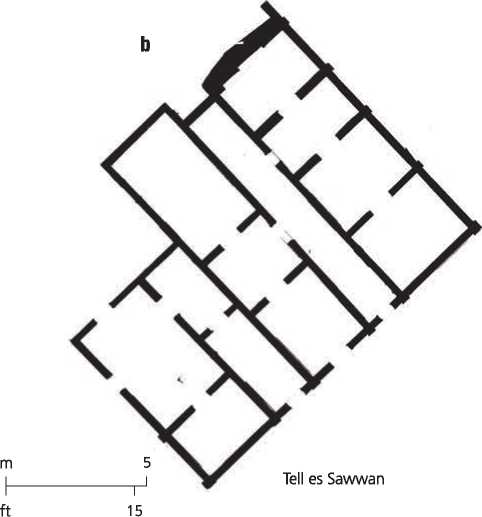

Most villages of that time seem to have had similar cult structures with only slight variations, even though the ones at Tell es-Sawwan were the largest. The cult rooms at Yarim Tepe, however, had a hearth possibly associated with ritual practices, while a sequence of rooms at Choga Mami may have served as a cult center dedicated to a mother goddess or fertility deity. The cult center at Songor differed in so far as several rooms were connected by centrally located doorways. All of these structures are oriented toward Tell es-Sawwan, which led scholars to surmise that the cult being practiced here had a supra-regional import. In fact, the graves at Tell es-Sawwan are so numerous that it is possible that it was a regional burial ground dedicated specifically to children (Figure 8.20).

Tell es Sawwan, Iraq, comparison of cult buildings In the region. Source: Mark Jarzombek/ Donny George Youkhanna, The Architecture of the Sixth Miiiennium BC in Teii es-Sawwan (London: Nabu, 1997), 21

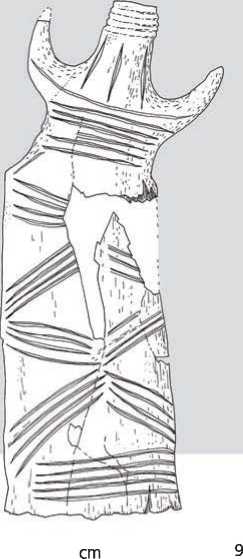

The burials were commonly accompanied by small figurines of alabaster, the source of which was some distance to the north, indicating far-ranging commercial dealings (Figure 8.21). The gender of these figurines is ambiguous and it was thought that since many of these figurines were found in children’s graves they either represent a type of mother goddess accompanying a deceased child or perhaps their embodied spirit at an older age.16 What the accompanying figurines represented is not clear especially since they are found only in Tell es-Sawwan’s infant graves. One unusually rich grave of an adult was furnished with six such statuettes along with vessels, alabaster animal figures, and turquoise beads. Small figurines of baked and sometimes unbaked clay representing both human and animal forms also begin to be found. Their remarkable diversity precludes any single explanation of their purpose.

The small complex at Ein-Gedi in Israel contains four primary components: a courtyard, two broad rooms, and a gatehouse situated on a promontory overlooking the Dead Sea, between two springs. In the center of the courtyard there was a sacred tree. In the main, rectilinear room there was a stone bench on the long walls. Opposite the entrance there was a white limestone drum that served probably as an altar. A ceramic bull, or perhaps a ram, carrying two churns was recovered nearby. The floor was perforated with a series of small shallow pits about 50 centimeters across that contained ash and were used for small fires lit beneath special bowls designed with legs that sat in the hearths. Given the formalized nature of the setting, this place was probably controlled by a ritual specialist. People came here to make ofierings.17

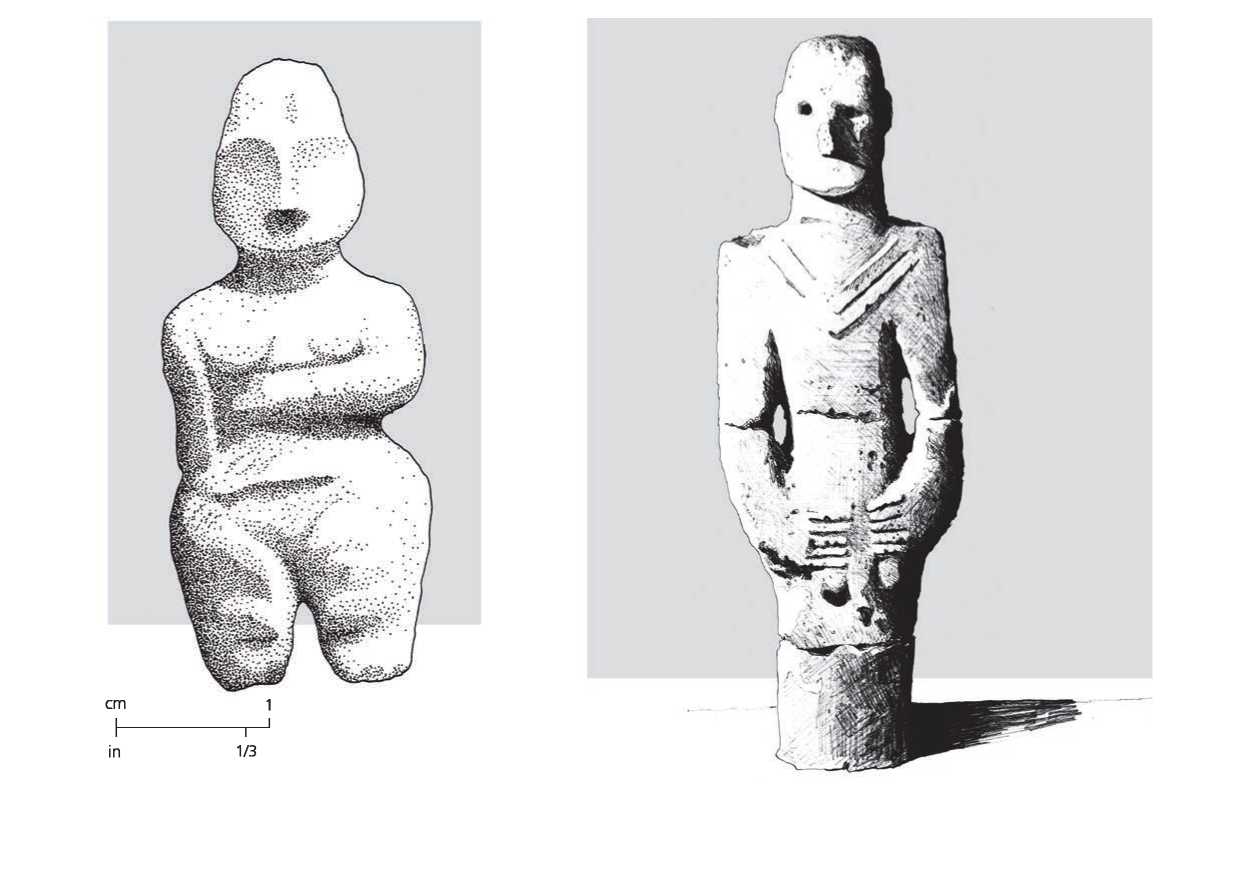

T Figure 8.22: Balzklzgol statue, Tell es Sawwan, Iraq. Source: Mark Jarzombek

Around this time, people also began to develop human-scale representations of deities, as, for example, the “Balzklzgol statue” (Bolikli Gol) as it is called, found near Sanilurfa in central southern Turkey. It is a 2-meter-tall figure of a man carved from limestone, with eyes of obsidian. The statue is believed to represent the God of Reproduction. He is wearing a Z-shaped vest or perhaps gold chains. His penis would have been in wood (Figure 8.22).

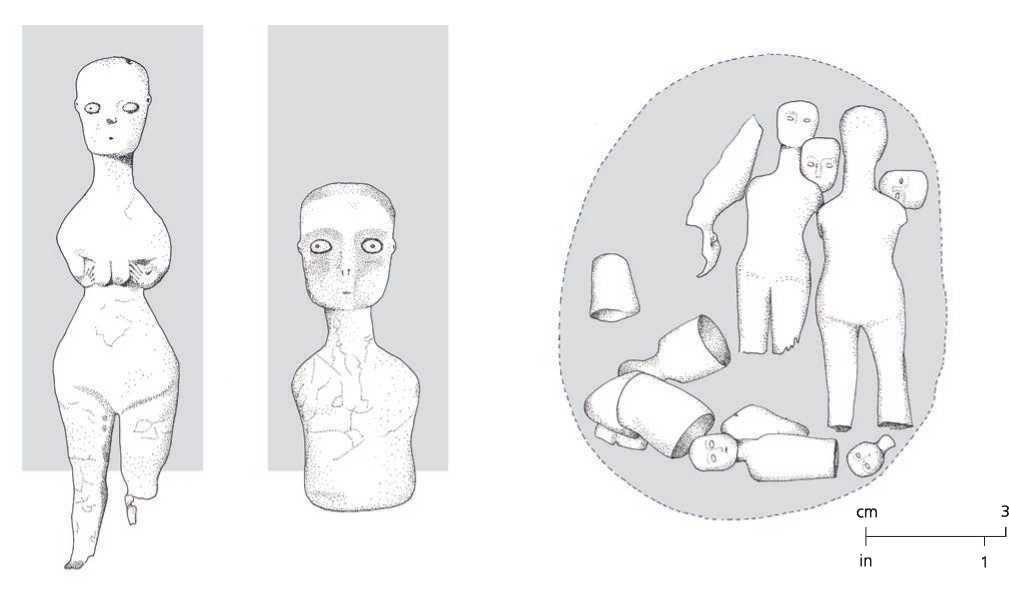

Figure 8.23: 'Ain Ghazal, Jordan, pit with plaster statues. Source: Mark Jarzombek/Jacques Cauvin, The Birth of the Gods and the Origin of Agriculture, translated by Trevor Watkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 111

There must also have been some relationship between the removal of the heads of those interred in the house floors and the discovery of a large number of plaster heads and anthropomorphic statues buried in pits in the vicinity of buildings that probably had ritual functions. A few of these astonishing sculptures, as at ’Ain Ghazal, are half-size human flgures modeled in white plaster around a core of bundled twigs. Clothes, hair, and in some cases ornamental tattoos have been painted on them. The eyes are created using cowrie shells and bitumen for the pupils. Thirty-two of these flgures were found at ’Ain Ghazal in all, flfl:een full flgures, flf-teen busts, and two fragmentary heads. Three of the busts were two-headed (Figure 8.23). The largest collection of plastered skulls comes from Tell Ramad, Syria, where twenty-three skulls were found of men, women, and even boys. On some, the foreheads or top of the head bore a large red spot; the eyes were made of grayish plaster with the iris and pupil standing out in pure white. With others, the entire skull was painted red. They were seemingly exposed for display. One group was in a niche of the outside wall of a building. Some were placed against the stone foundation. The skulls at Beisamoun and Kfar HaHoresh were oriented east. The high density of inhumations around the plastered skulls at ’Ain Ghazal, Beisamoun, Kfar HaHoresh, Jericho, and Tell Ramad suggests the possibility of communal and perhaps regional mortuary centers. Archaeologists are unsure what to make of these statues. Were they ancestor cults? Then how do women and children flgure in this? The same is true if they were enemy trophy heads.

World History

World History