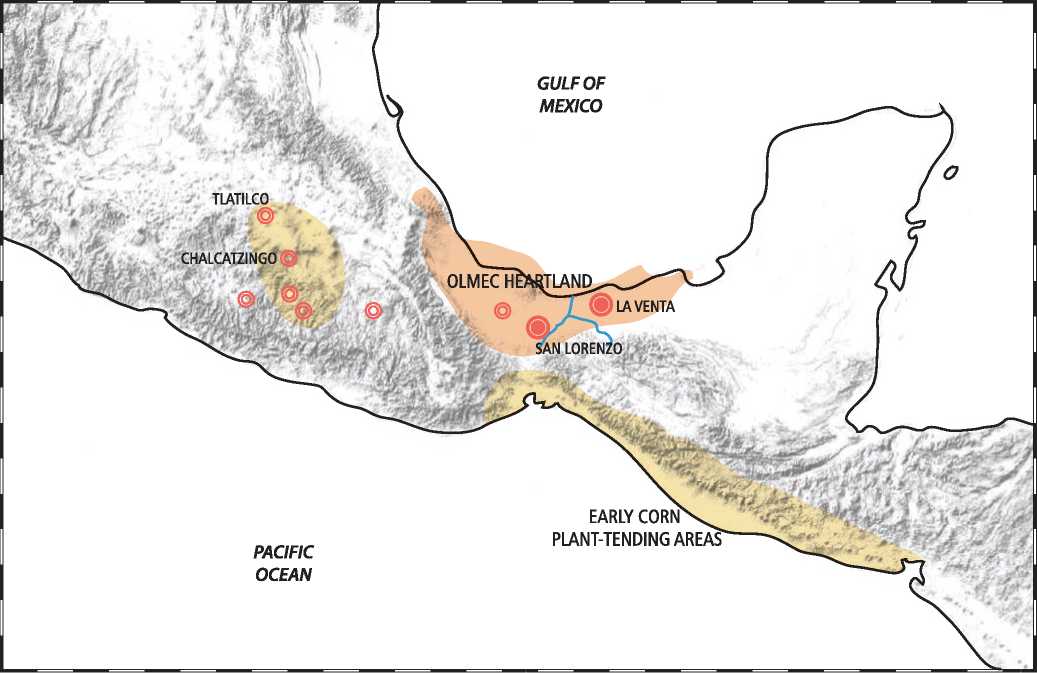

The first society to organize the agricultural revolution into a new scale and into a new type of polity were the Olmecs (1500-400 bce), who were also the first culture in Central America to produce architecture out of stone (Figure 11.6). Their heartland, however, was not in places where agriculture was developing, but in the low-lying marshy areas of eastern Mexico. Even a cursory glance at GoogleEarth shows the difierent ecological foundations of the Tlatilco and Olmec areas. The Tlatilco culture was situated in the large upland region of central Mexico that in GoogleEarth has shades of brown and speckled green; settlements were tucked along the marshes and streams of the valley bottoms. The Olmecs were in the swampy flatlands that stretch in a lush dark-green some 500 kilometers along the coast and penetrate in a giant arc 100 kilometers inland. Whereas Tlatilco areas permitted an integrated hunting and plant-tending way of life that had its roots in thousands of years of practice, the swamps did not. The only wildlife of any size in Olmec areas were turtles and birds. This was no Mississippi River Basin that permitted an affluent First Society to develop and it was probably only sparcely populated.

Perhaps the eruptions of various volcanoes played a part in the history of this region. In 400 ce, an eruption of the volcano Xitle put an end to Cuicuilco, covering the entire site in meters of lava. Two hundred years later, the enormous Popocatepetl volcano erupted and then again around 200 ce and in 823, all of which put a damper on the development of the more northerly region.

14 38 10 N, 91 44 00 W

Figure 11.6: Olmec world. Source: Florence Guiraud

But the Olmecs do not seem to have come from this northern area. Instead they probably originated from Pacific coastal areas near Guatemala. There, as at Takalik Abaj, in the dense tropical jungle, 40 kilometers from the Pacific Ocean, plant tending had already developed its unique cultural imprint. The people there, however, did not need irrigation. As important as this place was in providing obsidian and other raw materials, it was not until about 500

BCE that they began to build monumental architecture, in other words, well after the Olmecs had made their move. Regardless of their origin, the Olmecs came to the region specifically to transform it from swamp to a corn-producing, cult center controlled by powerful personalities, who were probably part shaman, part deity, part ruler. It might be a stretch to compare the situation to the difierence in our modern day between a family farm and a corporate one, but holding this difierence in mind, even in general terms, will orient us more to the drama set in play by the Olmecs. This was no gradual expansion of plant-tending lifestyles. This was the purposeful industrialization—and ritualization—of the landscape. And since the risks were enormous, the need for control was paramount. Corn was now not a plant, but a god.

By 1000 BCE, the Olmec organization skills were such that their influence soon extended in an arc of about 200 kilometers along the southern shore of the Gulf of Mexico on the coastal plains of Veracruz and Tabasco.6 They also created a city, San Lorenzo, that had substantial reservoirs and drainage systems integrated into a palatial complex with causeways, plazas, and platform mounds. It was a focal point for trade throughout Mesoamerica, and for good reason. The immediate area was relatively poor in raw materials. They got their jade from places in Guatemala. Red ochre needed for rituals was brought from the northwest in the Almagres area. Basalt for statues and buildings was brought from the slopes of Cerro Cintepec, one of the volcanoes of the Tuxtla Mountains some 60 kilometers away. Obsidian came from even farther afield, from central and western Mexico. The discovery of jade sources in the Rio Motagua Valley in Guatemala around 900 bce and the perfection of lapidary technology required to work this intractable stone into jewelry, figures, masks, and implements gave the Olmec elite a new and potent token of prestige. In return they had salt, which was used as a type of currency, rubber from a tree that they isolated and developed, and tar, which bubbled up from the ground in various places in the Olmec heartland. Tar was used to waterproof boats, but was also used in rituals. The word Olmeca (“rubber people”) is in fact an Aztec name given to the people who lived in this region. But it was corn that was at the core of their worldview. The scale of its production is only now becoming clear. So aware were the Olmecs of the significance of the maize revolution that corn was represented in the headdress of the king. Later in the Maya creation story, humans were literally created from maize.

The Olmec corncob was about a third of the size of the modern version. It also came in different variants, allowing for growers to fit difierent corns to the difierent nutrient conditions of the land. That the Olmecs could accomplish this had a lot to do with their location. Large rivers flooded the plains and renewed the soil, yielding wide stretches of tall grass that was chopped down in November when the floods receded. Based on practices that are still used today in this region, we know that Olmec growers piled the grass in rows where as it began to rot it would serve as mulch for the corn, which was grown between the rows. The corn was harvested in spring before the rains. There was also a rainy season crop planted in the uplands above the flood plain in late May and harvested in October.

The dual planting season not only transformed the Olmecs into a corn-producing machine, but it also required an organization far difierent from the informal village life of earlier times. Extremely hierarchical, Olmec culture centered on rulers whose images were carved on gigantic basalt stones, brought laboriously by boat and sledge from the mountains. Unlike the angular and sharp features of later Mesoamerican civilizations, the Olmec heads were round and soft, and very lifelike. Some of these heads were over 3 meters high. No two are alike and thus clearly represent individual people. They wear helmets of leather. How they were carved out of the hard stone without metal tools boggles the mind. The Olmecs made not only big things. They also carved miniature figurines as well as statues of men at a life-size scale. Their sensitivity to the human form is astonishing and equals if not surpasses the sculptural skills of later Mesoamerican civilizations. In 800 bce, no other culture in the world had achieved such a level of aesthetic confidence.

Caves, springs, and volcanoes figure prominently in the Olmec consciousness, all integral to shamanistic practices. The volcano was associated with the world being born from below, but was also viewed as the home of the storm clouds, lightning, and rain. A dragon with a gaping mouth represents the portal to this underworld. The sky was ruled by a bird monster or sun god whose energy powered the cosmos and made the plants grow. Underneath the dragon the Olmecs visualized a watery void out of which the world was formed. The main deity in their mythology was the rain god depicted as a jaguar, a shamanistic symbol of transformation. This jaguar could assume other forms, even human ones. The mythological union of a woman and a jaguar produced a special class of gods that were represented in sculpture as having a snarling mouth, toothless gums, fangs, and a cleft head.

Mirrors of polished iron ore were also found. These small concave mirrors may have symbolized a prototypical Tezcatlipoca, the later patron god of the Aztec royal house, whose essential aspect was the mirror with which he looks into the hearts of humans and divines their future.

Ball playing was also an element of Olmec ritual as evidenced by clay figures showing players wearing heavy, leather belts and possibly headgear. It seems that the ball players also wore mirrors, giving us some indication of the magical nature of what we might naively call games. The games are one of the least understood elements of Mesoamerican culture, though it is likely that they originated in the low-lying tropical zones home to the rubber tree. One candidate for the birthplace is along the coastal lowlands along the Pacific Ocean, such as at Paso de la Amada where a court was discovered that dates to 1400 bce. But it was the Olmecs who elevated it to ritual status. Soon, every center had to have a court. Some cities had several. Today, archaeologists have identified over 1,300 Mesoamerican ball courts. Balls ranging from 10 to 22 centimeters have also been found, most as part of buried ritual ofierings. They are heavy, namely 3 and 4 kilograms. In a modern-day game, known as ul-uma, that is played in some Mesoamerican villages, the play resembles a net-less volleyball, with each team confined to one half of the court. The ball is hit back and forth using only the hips until one team fails to return it or the ball leaves the court. But why the games were held and what they signified is not known. Were they to defuse or resolve conflicts, struggles to the death by captives, or symbolic activities associated with calendric events and shamanistic practices?

World History

World History