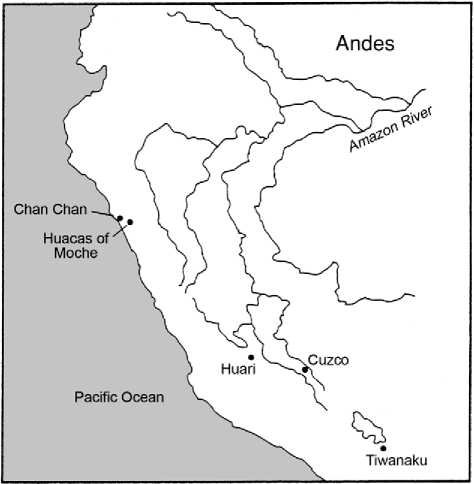

The capitals of late prehispanic Andean empires were sizeable cities, with populations in the tens of thousands (Figure 8). Researchers have not reached a consensus regarding the antiquity of the first Andean cities and the development of the first centralized state governments. Despite ongoing debate, the Mochica, Wari, and Tiwanaku can be considered to have been early states in their respective regions and provide case studies for exploring urbanism and the rise of civilization. The capitals of these polities bear witness to the transformations concomitant with the establishment of centralized state governments.

Huacas of Moche

The capital of the Mochica state was located at the mouth of the Moche Valley, at a site comprising the Huaca del Sol, Huaca de la Luna, and the intervening valley bottom. This site, which spanned more than

Figure 8 Schematic map of the Andes showing locations of early cities.

72 ha and had a population estimated in the thousands, is known today as Huacas of Moche. The principal monuments were laid out so as to capitalize on natural topography while also bounding the area of urban residential population. A major avenue sets the Huaca de la Luna and adjoining elite residences apart from the urban residential area (Figure 9). The two huacas appear to have been used by elites as part of the religious and political activities of the state - other ceremonial activities are known to have been conducted in nearby elite households.

Recent excavations have revealed that the area between the major civic-ceremonial complexes was densely occupied in the Moche IV period (CE 400700). Researchers have identified multiple domestic compounds that are thought to have been the residences of extended family units. Compounds were enclosed groups of rectangular structures of varying size and construction quality, which contained modest open spaces and storage facilities. These units were separated from each other by narrow streets (generally less than 2 m wide). Excavations have revealed that the occupants of these compounds were generally not a farming population, but were mostly craft specialists - evidence of weaving, ceramic production, shell working, smelting, and the working of lapidary ornaments has been identified, while farming and fishing tools are virtually absent.

The rise of Mochica civilization included the extension of administrative control or hegemony over a

Figure 9 Urban compounds at Huacas of Moche site.

Number of coastal valleys to the north and south of the Moche Valley. In some areas, local settlement patterns were disrupted as secondary administrative sites were established and irrigation systems were extended. The Mochica capital itself seems to have grown and been laid out to meet the new needs of state administration. Monumental building projects increased dramatically at the capital, with elites directing the construction of not only the major hua-cas, but also palatial residences and elaborate tombs. Specialized craft production also increased at this time, and major agricultural intensification projects were completed as well.

Wari and Tiwanaku

The Wari and Tiwanaku polities were the first states to develop in the central Andean highlands and the Titicaca Basin, respectively. Both polities are known to have had urban capitals that developed around the time of the first territorial expansion outside of their core regions. Wari and Tiwanaku secondary centers and provincial outposts were constructed with certain aspects of an urban template in mind, but the populations of secondary sites appear to have been too modest to consider them as cities.

Tiwanaku At its maximal extent, Tiwanaku was a city of 6 km2, with a population estimated in the tens of thousands. At the center of the city lay a ceremonial precinct that was surrounded by a large artificial moat. Certain of the city’s most important monuments are located within the enclosed area (viz., the Kalasasaya and Sunken Temple), as are residential compounds identified as elite and royal palaces. The inner city at Tiwanaku was renovated after CE 800, replacing previous residential areas with a smaller number of compounds occupied by elites with close ties to state ceremonial activity.

Outside of the urban core, archaeologists have excavated domestic compounds interpreted as the residences of minor state officials. These exhibit a degree of central planning and take the form of walled compounds that contained the residences of extended families. Streets and drains separate these compounds and provide access through the site. Some workshops have been identified in the outer part of the city, but the residences of craft specialists have been difficult to identify unambiguously. Agricultural laborers lived mainly in the city’s hinterland, near to the system of raised fields that provided sustenance for the population of the Tiwanaku heartland.

Huari The Wari state developed in the Ayacucho region of highland Peru. Its capital (Huari) was established on the site of several previously autonomous settlements, growing from c. CE 400-900 and exhibiting the characteristics of an urban center by the seventh century. The urban core of Huari was 4 km2 at its maximum extent and contained several monumental religious complexes, areas for public feasts, storage facilities, and residential compounds. Walled temple compounds such as the Semisubterranean Temple and the Vegachayoq Moqo complex were laid out and separated by narrow streets, and domestic architecture in later phases takes the form of walled compounds as well. As domestic residential blocks filled in the open areas between religious complexes, the city grew more crowded, and second-story architecture was built. Residential compounds were laid out as walled enclosures in which a series of halls and smaller rectangular structures were built around a central patio area. The excavated assemblage in these compounds has been interpreted as belonging to mid-level state officials.

The first cities in the Andes grew rapidly, outpa-cingsimilar growth processes at secondary centers (e. g., Lukurmata, Conchopata). As capitals of early states, these cities grew around precincts of monumental religious architecture in which elite residences have been identified. Open spaces for large-scale gatherings and feasts were built as part of the major religious complexes, and more modest plazas are often found in elite residences. The occupants of these early cities included the ruling elite, minor state officials, and artisans whose workshops tended to be located outside the main religious-administrative areas. Housing tends to take the form of walled compounds in which extended family groups resided. Residential blocks were separated by streets that appear to have been narrow and opportunistically built, although there is evidence that the state did lay out major avenues and invested in programs of urban renovation resulting in better access and urban infrastructure.

See also: Africa, North: Egypt, Pre-Pharaonic; Americas, Central: Classic Period of Mesoamerica, the Maya; Postclassic Cultures of Mesoamerica; Americas, South: Inca Archaeology; Asia, East: Chinese Civilization; Asia, South: Indus Civilization; Asia, West: Achaemenian, Parthian, and Sasanian Persian Civilizations; Mesopotamia, Sumer, and Akkad; Cities, Ancient, and Daily Life; Classification and Typology.

World History

World History