The next stage in the evolution of shipbuilding technology was the building of coherent hulls made of more than one piece of timber. Based on actual archaeological data, this important step is attributed to the Egyptians, who in spite of not being a seafaring-oriented society, managed to produce some of the first multiplank hulls in the world. As the ship finds from Abydos, Cheops, Dashur, Liszt, and the tomb depictions of courtier Ti show, the irregular planking of these hulls were joined in most cases by lashing with vegetable cord and with mortise and tenon joints, the former being adopted from reed boatbuilding while the latter being borrowed from general carpentry (Figure 2). This type of joint would remain in use for more than four millenniums, becoming a hallmark of Mediterranean shipbuilding. The quest of joining multiple planks into one coherent structure was, nevertheless, tried in other parts of Europe, the best example coming from the Greek Islands, especially from Syros where the third millennium BC terracotta ‘frying pans’ are considered one of the earliest ship models, and from the British Isles, as the boat remains from North Ferriby, Caldicot, Brigg, and Dover have shown. Here, the main fastener used to hold together the carefully worked planks was the cord. The sewing technique survived in each of the aforementioned European regions, including Northern Europe, as relicts of older boatbuilding traditions were depicted in the multitude of ship representation carved in different places

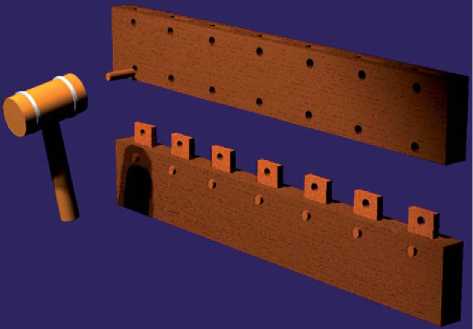

Figure 2 Planks joined by mortise and tenons affixed with wooden pegs.

Throughout the Scandinavian Peninsula. The cord, as universal hull fastener, was replaced in the Mediterranean by the mortise and tenon joining, which in turn would be replaced later during the first millennium AD by treenailing and metal nailing. This coarse evolutionary outline, however, did not happened everywhere as the stitched hulls of the shipwrecks from Giglio, Bon Porte, Comacchio, Marseille (Jules Verne 9), Cervia, Aquilea, and Ma’agan Michael (partially) have shown.

The mortise and tenon joinery used to join the flush-laid planking in wooden hulls bloomed especially during the first millennium BC when the Phoenicians, followed by Etruscans, Greeks, and other people, led the way in the colonization and exploration not only of the entire Mediterranean realm, and as the fifth century BC voyage of the Carthaginian Hanno shows, but also beyond the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar Strait). Their main concurrent, the Greeks, made an early debut in the Mediterranean during the last centuries of the Late Bronze Age, by continuing the art of building seagoing ships of their earlier predecessors, the Minoans from Crete (the best example being the elegant ship frescoes from Thera Santorini). The vestiges of Greek seafaring are found not only at the bottom of the sea, but also in the poetic rhymes of mythological verses of Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad (for the Aegean and Mediterranean seafaring) and the legend of the Argonauts (for the Black Sea seafaring). The Greek wars against almighty Persian fleets and especially their quest of coastal land propitious for the foundation of new city-states led to the perfection of several ship types, such as the famous warship, the trireme, and the less famous but clearly most efficient cargo ship illustriously represented by the Kyrenia vessel.

The apogee of multiplank hull building happened later at the beginning of our era when the

Mediterranean became a Roman ‘lake’. Initially a state with a clear land orientation, the Romans realized during the first Punic War (BC 264-241) that control on the sea is the key to supraregional hegemony, hence their swift adoption of nautical skills from their most powerful competitors, the Carthaginians and the Greeks from Magna Graecia. The Roman period (c. BC 250-500 AD) witnessed not only devastating sea battles but also intense commercial shipping in the whole Mediterranean realm, the North Sea, the English Channel, the Black Sea, and the Aegean, and on inland waterways, specifically on the Rhine, Rhone, and the Danube. Shipping lanes connected all major Mediterranean ports-of-call (Alexandria (Egypt), Caesarea Maritima (Israel), Athens (Greece), Syracuse (Sicily), Pompeii (Italy), Cadiz (Spain)) with Rome’s harbour in Ostia. The large volume of seafaring unavoidably left behind a rich collection of wrecked vessels of all sizes and types, with large wreck concentrations in the Lyon Bay, the Ligurian, Tyrrhenian, and the Adriatic Seas. Adaptation to local environments and adoption of non-Roman nautical technology led to advances in shipbuilding and ship navigation. After more than half a century of research, nautical archaeology revealed that ship types were even more numerous and functionally adapted than those shown on the Late Roman (third to fourth centuries AD) Altiburus Mosaic. The complete investigation of the Madrague de Giens wreck (BC 60) showed how merchantmen of the corbita and ponto types could carry thousands of amphorae in just one shipment; from a constructional point of view, these double-planked hulls (outer layer of pine, fabric between plank layers, main dimensions

L 40 m, B 9 m, H 4.5 m, hull sheathed with lead, bolted frames to keel) were indeed the flagships of the Mediterranean mortise and tenon strake-joining.

But in spite of the introduction of certain standardization procedures in shipbuilding (metrological standardization of scantlings) as the large Zwammerdam prams in the Netherlands have shown, the Romans were not able to displace techniques used in local shipbuilding, their mixing with Roman technological traits being apparent in both seagoing and inland craft. The Barland’s Farm (Wales, Great Britain) wreck (c. 300 AD), for example, representing a double-ended, small-sized, coastal vessel with mixed propulsion, was built flush-laid oak planking nailed to the framing in a kind of ‘frame-first’ construction, the nails being driven through treenails and double-clenched afterward. The other important examples come from the Rhine area: in Mainz, Germany, five medium-size military vessels that patrolled one of the most disputed borders of the Roman Empire were built with clenched iron nails instead of the Mediterranean mortise and tenon joinery (Figure 3). The joinery is thought to have been typical of the Romano-Celtic shipbuilding tradition, which, as the Bevaix and Yver-don craft have shown, was characterized by the use of sturdy flush-laid oak planks fastened not to each other but to a heavy framing inside the hull.

World History

World History