FIELD ARMOR

Medieval body armor consisted of chain mail, a strong mesh of small iron rings. Although this type of armor allowed great flexibility, that very attribute was its weakness. There was no rigid resistance against the points of arrows and spears and against bludgeoning from missiles such as stones and rocks. Chain mail was later supplemented with plates of solid bone, leather hardened by boiling, and steel. By the 14th century, soldiers were protected by plates of metal attached to a heavy fabric vest, with separate plates shielding the arms and legs and a metal helmet for the head. The development of tempered steel crossbows and efficient firearms, however, necessitated additional protection. Between 1400 and 1600, as advances in technology improved offensive capabilities, defensive tactics and weapons also were improved, and military budgets rose at astronomical rates. The most skillful armor makers during the early Renaissance were in Milan, and by 1420 they had created a full suit of plate armor. Moderate flexibility was achieved by overlapping or interlocking the plates, which were connected by leather straps or rivets. Even for a relatively large combatant, a suit of field armor rarely weighed more than 60 pounds; unwieldy, heavy armor would have been disastrous in warfare. The steel in 15th-century armor was extremely hard, designed to deflect arrows and blows from pikes, swords, maces, and other weapons. Steel of this hardness, however, could split or shatter if fired upon by guns. A soldier with slivers of steel embedded in his flesh was much more susceptible to infection than a soldier wounded by a simple musket ball. Although armor makers attempted to produce steel that was more pliant and could bend slightly instead of shattering, they were not very successful. In the end the only effective method for making armor resistant to

Handbook to Life in Renaissance Europe

Firearms was to make it thicker, and soldiers could not fight when wearing full body armor thick enough to resist fired projectiles. The answer was to focus on vital parts of the body, including the head and torso, and heavy breastplates and plates for the back replaced full armor by the end of the 16th century. Armor for horses during the Middle Ages consisted of chain mail extending over the tops of the legs and a helmet of chain mail. Cavalry horses during the Renaissance also had armor, including a helmet covering most of the head. While horse helmets often were made of thick leather, the body armor of horses consisted of curved or interlocking metal plates, with raised bosses for deflecting arrows and other projectiles. The legs, however, were left uncovered for speed and mobility.

TOURNAMENT AND PARADE ARMOR

Tournament armor during the Middle Ages was the same used as field armor. During this period tournaments (or jousts) served as training and conditioning for actual warfare. Men were sometimes killed during tournament competition, which could be brutal. By the 15th century, public tournaments resembled sporting events, and specific armor was used for each type of competition. Because tournament armor was worn only a short time for a specific purpose, it was thicker and heavier to provide maximal protection for the participant. This armor sometimes required a winch to lift a knight onto the horse, and anyone wearing such armor often could not stand up in it after falling to the ground. Firearms were not used during Renaissance tournaments; the usual weapons were lances for horseback contests and swords and axes for fighting on foot.

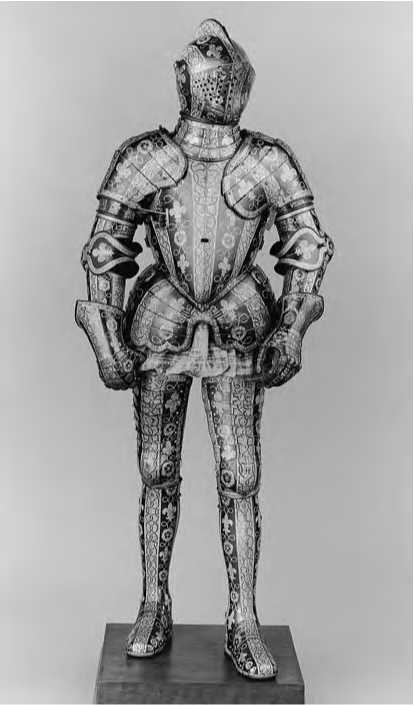

Parade armor, which evolved during the early 16th century, was not worn in any type of battle, including tournaments. All Renaissance armor was decorated, even if only with a narrow band incised around the edges; however, parade armor was magnificently ornamented, for both knights and horses. Artists such as Holbein and Durer made designs for etching on armor. The three techniques for armor decoration were etching, embossing, and damascening, in conjunction with gilding and bluing. Inlays often consisted of gold and silver. Parade

7.1 Armor of George Clifford, third earl of Cumberland, c. 1580-85. Made in the royal workshops, Greenwich, England. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Munsey Fund, 1932 [32.130.6])

Armor was a symbol of status and power, and ancient Roman motifs were used in the ornamental imagery. Classical figures were displayed alongside biblical quotations and saints, with heraldic designs proclaiming the wearer’s identity and rank. Parade shields gave artists an especially cohesive surface for creating elaborate designs; the inner surface of these shields was sometimes lined with fabric and painted with hunting scenes or other appropriate motifs.

World History

World History