Elections in the United States since 1968 have been anything but consistent. In 1984 President RONALD W. REAGAN carried the highest popular vote (more than 54 million), the highest number of electoral votes (525 out of 538), and the most states (49, tied with President Richard M. NiXON in 1972, although Nixon won only 43.3 percent of the popular vote in 1968) of any president in history. Yet, just eight years later in 1992, President William J. Clinton entered the office with only 43 percent of the electorate as well. In the 2000 presidential election, however, it was nearly a dead heat between George W. Bush and Albert Gore, Jr. The participation rate of the voting-age population declined 10 points after 1968 and has remained relatively steady since. During the 1960s, turnout for presidential elections hovered between 60 and 64 percent, and the percentages for off-year (nonpresidential) elections stayed in the upper 40s. Beginning in 1972, turnout has fluctuated between 49 and 55 percent, with off-year elections following similar patterns in the upper 30s. These numbers might suggest declining voter participation. The number of eligible voters increased after 1968 as a result of immigration and civil rights initiatives, but the percentage of active voters—those voting—has remained relatively constant since World War II. Exactly why voting participation has declined—or if it has declined in any significant way—remains a point of discussion among scholars.

In general, the American electoral college system discourages third-party candidates. Each state is given a number of electoral votes equal to its combined number of senators and representatives in Congress. After a presidential election, the popular vote is tallied in each state and the party with the most votes takes all the electoral votes. The candidate with a majority of the 538 electoral votes wins the office. The framers of the Constitution developed this system to include a territorial representation among the popular vote; a strict popular voting system might provide large population centers with a greater political voice than rural centers. For example, three cities of 10 million residents would have more voice than 10 states with only 2 or 3 million people each. In the 18th century, this was of particular concern, since the more rural southern states shared interests that were at odds with the more populated northeastern states. Since candidates must secure majorities in multiple states to be able to have a chance of winning the presidency, American politics favors the candidate with the strongest party mechanism. Most voters prefer not to support a candidate from a nonestablished party, and as a result most third-party presidential candidates face overwhelming odds.

Since the Civil War, third parties received electoral votes only six times, the last occurring in 1968 when American Independence candidate George C. Wallace managed to win 46 electoral votes. Only Robert LaFol-lette (1924) and H. Ross Perot (1992) managed to win even half the votes of the first runner-up. Despite these odds, third-party candidates can carry significant influence in national elections. With the exceptions of John F. Kennedy in 1960 and George W. Bush in 2000, every one of the 15 presidents elected with a minority plurality lost his majority to a strong third party. Most often, the third-party candidates splinter votes from a major party to give the election to a minority candidate; in 1912 President Woodrow Wilson won after Roosevelt stripped Taft of more than half his votes; in 1992 President Clinton won after Perot diverted votes away from George H. W. Bush (although some observers said that Perot drew an equal number of voters away from Clinton); and in 2000, George W. Bush won after Green Party candidate Ralph Nader took votes from former vice president Gore.

A more dispersed constituency distinguishes the third-party campaigns of 1992, 1996, and 2000 from campaigns in 1972 and before. In prior elections, serious third-party candidates enjoyed clear demographic advantages in at least one or more states. In 1968 segregationist George Wallace received 46 electoral votes from just over 13 percent of the popular vote, because he held strongholds in five southern states and represented a strong local constituency. In contrast, Perot garnered nearly 20 million votes and 19 percent of the popular vote, and yet earned no electoral votes in the 1992 election; nor did he gain any after winning 8 percent and 8 million votes in 1996. This was because Perot’s Independent Party and later Reeorm Party had no central stronghold; he gained national recognition through media outlets and not from a local constituency base. The Green Party’s Ralph Nader received fewer than 3 million

Votes in 2000 (2.7 percent) but probably had an effect on the election. Democrat Gore edged Republican George W. Bush in the popular count by half a million votes, but Bush achieved a narrow victory with 271 electoral votes, one more than required, after a controversial dispute over Florida’s election returns. Three previous presidents won elections despite losing the popular vote: John Quincy Adams in 1824, Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, and Benjamin Harrison in 1888. In 2000 controversy again erupted when Gore challenged the Florida election results. Voter exit-polling had indicated a Gore victory in the state, but a high level of disqualified ballots had left Bush with a lead of 327 votes out of some 6 million cast. Gore sought to have the ballots reexamined in four populous counties. A highly charged legal and political struggle ensued in which both candidates maneuvered to ensure their victory through the courts. On December 8, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a reexamination of the rejected ballots across the state, but the next day the U. S. Supreme Court stayed this decision. On

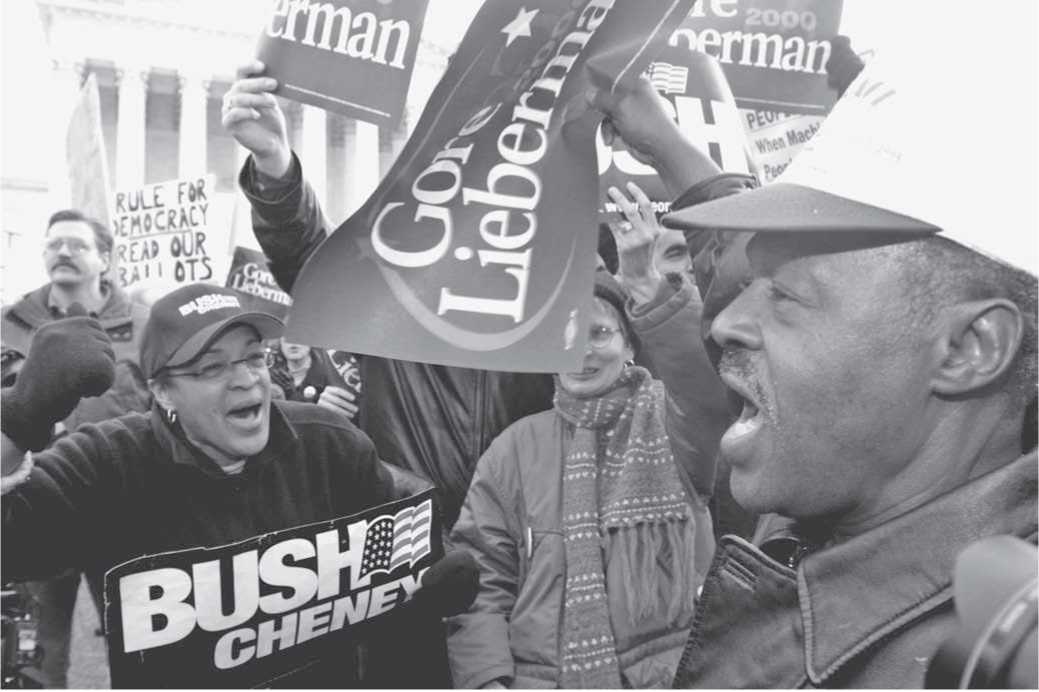

Gore and Bush supporters face off during a protest December 11,2000, outside the U. S. Supreme Court in Washington,

D. C. (Wong/Newsmakers)

December 12, the Court found 7-2 that Florida’s law was flawed because it lacked uniform counting standards and further ruled, 5-4, that time had run out for recounts, effectively confirming a Bush victory.

Some opponents of the electoral college used the public anxiety over the 2000 election to push for electoral reform, specifically by ending the electoral college system altogether in favor of a strict popular vote. Supporters of the current system criticized these alternatives with many of the same arguments posed by the original framers of the Constitution, primarily that direct election of the president would provide advantage to urban centers. The 2000 election suggests that the interests remain divided; Gore’s 1 percent popular advantage arose from a small number of large urban centers on the East and West Coasts, where he gained 71 percent of the vote. On a rural level, however, President Bush won a 78 percent majority of the voters; or 2,434 of the nation’s 3,111 counties—leaving Gore with only 677.

The 2004 presidential election featured a race between Democratic senator John Kerry of Massachusetts and incumbent Republican president George W. Bush. Senator John Edwards (D-N. C.) was selected as Kerry’s running mate, and Vice President Richard B. Cheney remained the vice-presidential nominee. Rather than run as the Green Party candidate, Ralph Nader chose to run as an independent in 2004. Other third-party candidates included Libertarian Michael Badnarik and David Cobb of the Green Party.

Since this was the first presidential election after the terrorist attacks in New York City and on the Pentagon in September 2001, American EOREIGN policy emerged as an important theme in the campaign. President Bush, citing the terrorist attacks and the Iraq and Aeghanistan Wars, argued that the most important issue facing America was national security. He also labeled John Kerry as a “flip-flopper” who could not lead the nation in moments of crisis. John Kerry often cited his military record in Vietnam, where he earned a reputation as a leader. Kerry’s image, however, was marred by a campaign by the Swift Boat Veterans and the POWs for Truth, who questioned Kerry’s service and the operations he led. Kerry also argued that under President Bush’s administration, global support of American foreign policy initiatives had drastically declined as the Iraq War continued to worsen. Kerry contended that he would try to repair these relationships. The three presidential debates held in the fall also focused on foreign policy issues.

President Bush received 50 percent of the popular vote and 286 electoral votes. Kerry won 48 percent of the popular vote and 251 electoral votes. Kerry performed strongly on the West Coast and in large, industrialized midwestern states and the Northeast. George Bush secured the Midwest, several key western states, and the

South. President Bush was inaugurated to his second term on January 20, 2005.

The 2008 election became a historic first when voters elected the first African American, Barack Hussein Obama, to the White House. Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama, the junior senator from Illinois, easily defeated his Republican rival, Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.). Obama won 52.9 percent of the popular vote, which provided him with 365 electoral votes, while McCain received an anemic 45.67 percent of the popular vote for only 173 electoral votes. Minor presidential candidates received individually less than 1 percent of the popular vote, including Ralph Nader (Independent), Bob Barr (Libertarian), Chuck Baldwin (Constitution), and Cynthia McKinney (Green).

In a fierce primary race against Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton (D-N. Y.), Obama won the Democratic presidential nomination in a carefully orchestrated campaign that rallied voters to vote for change. The Republican Party nominated John McCain, a 71-year-old senator from Arizona and a former Vietnam War hero. A financial meltdown on Wall Street in October and President Bush’s handling of the Iraq War set the context for the campaign.

The presidential campaign proved to be the most expensive in American history, as Obama raised more than $731 million, while McCain relied mostly on public financing to fund his $345 million campaign.

Election Day revealed that voters were ready for change. Obama’s popular vote was about 2.5 percent more than President Bush had received in his reelection in 2004. Voter turnout was less than predicted but reached a historic high of 61 percent. Obama swept the Northeast and the Far West, as well as winning the swing states of Florida, Indiana, Virginia, New Mexico, Colorado, and North Carolina. Moreover, Obama won key constituencies among young voters aged 18-29 years (66 percent), African Americans (95 percent), Hispanics (67 percent), and Asians (62 percent). In addition, Obama won the female vote (56 percent), self-identified liberal voters (89 percent), self-identified moderates (60 percent), Catholic voters (54 percent), Jewish voters (78 percent), and gay and lesbian voters (70 percent), plus lower-income voters earning less than $50,000 a year and higher-income voters earning more than $200,000 annually. McCain faired well only among white voters (55 percent), voters over the age of 65 (53 percent), Protestants (54 percent), and self-identified conservative voters (78 percent).

Democrats won control of Congress, gaining 21 new seats in the House for a total of 257 members, giving the Republicans 178 members. In the Senate, Democrats gained 7 new seats to provide a 58-seat majority, while the Republicans held 41 seats.

A discontented electorate voted Democratic, which meant a vote for change.

U. S. Republican presidential candidate John McCain and his vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin at a rally in Hershey, Pennsylvania, October 28, 2008 (Getty Images)

See also Anderson, John B.; Buchanan, Patrick J.; Carter, James Earl, Jr.; Dole, Robert; Dukakis, Michael S.; Ferraro, Geraldine A.; Ford, Gerald R.; Jackson, Jesse L.; McGovern, George S.; Mondale, Walter F.; political parties; Quayle, J. Danlorth.

Steal the Election (Washington, D. C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 2001); Jeffrey Toobin, Too Close to Call: The Thirty-Six Day Battle to Decide the 2000 Election (New York: Random House, 2001).

—Aharon W. Zorea and Matthew C. Sherman

World History

World History