Like William Lyon Mackenzie King, Jean Chretien recognized that Canadians are nervous about change, welcome compromise, and support leaders who divide them least. Like other voters, they are easily bored. The rivalry between the Prime Minister and his finance minister might have entertained them, but beyond Martin’s insistence that he had single-handedly overcome the federal deficit, his campaign was mostly hidden until the end of May 2002, when Chretien dropped him from the cabinet. This precipitated a power struggle within Liberal ranks that was as unusual as it was unseemly. After much searching, Chretien chose John Manley as his preferred successor. Calm, intellectual, and a long-distance runner, Manley was as pro-business as Martin and a generation younger. His radicalism was limited to discreet criticism of the monarchy.

The 2000 election had taught supporters of right-wing politics the futility of a divided conservatism. To win the Progressive Conservative leadership, Peter MacKay pledged to a rival that he would never merge with the Alliance. The pledge was a political fib. Stephen Harper found MacKay an eager recruit. In 2004, the two men announced an unhyphenated and unabashed Conservative Party of Canada.

Although Canadians had rejected the compromises needed to make Quebecers more comfortable inside Confederation, they blamed Chretien for doing too little to avoid the diffhanger referendum of 1995. While endorsing Dion’s Clarity Act, Chretien also set out on a cruder strategy to make Ottawa, Canada, and, inevitably, the Liberals more visible in Quebec. He left the details to his Quebec lieutenant, Alfonso Gagliano. Using his own staff, political agents, and the few advertising agencies willing to forgo any business with Quebec’s pq government, Gagliano could claim by the early 2000s that sovereignty now appealed to fewer than a third of Quebecers and was fading fastest among the young. Under Lucien Bouchard, the pq had been narrowly re-elected in 1998, but his successor, Bernard Landry, lost to Jean Charest in 2003.

Conservatism was more acceptable to Quebecers and perhaps to other Canadians too. One reason was disillusionment with an aging federal government. Outrage after a young man murdered fourteen female engineering students at Montreal’s Ecole Polytechnique in 1989 had led the Liberals to propose a national long-gun registry. Resistance from rural areas, especially in the western provinces, so complicated the project that it ultimately cost a billion dollars to implement, with no apparent impact on violent crime. When Liberal deficit cutting slashed their funding, colleges and universities raised tuition fees, leaving new graduates with debt burdens their elders had never experienced. Advocates of universal health care had trusted in enhanced physical fitness to control costs. Instead, millions of citizens, often self-indulged and overweight, denounced waiting times and physician shortages. Conservatives argued for private, for-profit services so that wealthier patients could get faster service. Invited to rule that a constitutional right was involved, the Supreme Court ordered provinces to solve the waiting-list problem.

Many Canadians entered the new millennium in a grumpy mood. Spared a widely predicted computer programming disaster nicknamed “Y2K,” Canadians soon had plenty of other crises to worry about. New technologies linked them to work, family, and friends wherever they were. One result was a global awareness more likely to terrify than to empower. After many lifetimes of grumbling about long cold winters, Canadians learned that imminent global warming would flood coastal cities, devastate the Arctic ecology, and threaten their lives with global epidemics reminiscent of the Spanish flu of 1918-19. At Kyoto, the Chretien government nervously signed an international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Fast becoming the major foreign supplier of gas and oil to a non-signatory, the United States, Alberta refused to jeopardize its short-term prosperity to satisfy Ottawa Liberals. Didn’t provinces control their own natural resources?

The Liberals’ leadership struggle reached a crisis when the federal Auditor General claimed that millions of the dollars allotted to the Chretien-Gagliano “sponsorship” program had simply vanished. Sending Gagliano to Denmark as ambassador only intensified public outrage. Isolated in his own party by Martin’s relentless jockeying for control, Chretien finally announced his departure. On December 12,1993, he was gone. Martin and his supporters turned the occasion into a virtual change of government. Ambitious backbenchers, denied power during the Chretien years, took most of the portfolios. Gagliano was recalled from Copenhagen, and John Gomery, an appeal judge of the Quebec Superior Court, agreed to head a royal commission with full power to investigate the sponsorship scandal. Confident that most Canadians were as delighted that he was prime minister as he was himself, Martin called a general election for June 28, 2004.

Voters, in fact, felt otherwise. Most were sick of the Liberals and discouraged by politics. Most Chretien supporters sat on their hands. Furious at the implication that their allegiance was for sale, the sponsorship scandal drove Quebecers to Gilles Duceppe’s Bloc; New Democrats backed their earnest new leader. Jack Layton, a Mon-treaJer ejected as an activist Toronto alderman. Stephen FFarper’s Conservative message

Was determinedly moderate; but his campaign as a tightly programmed policy wonk was undermined each time the media found a Reform veteran eager to speak his mind. On election day, confusion, apathy, and the flaws of an imperfect permanent voters’ list kept almost half the voters at home. The rest elected 99 Conservatives, 54 Bloc, and 19 New Democrats, leaving Paul Martin 135 seats and a vanished majority. He swallowed his humiliation, reminded his party that it was stUl in power, and hunted for the tactics to win a majority.

Since Medicare seemed to be the voters’ top priority, Martin met the provincial premiers and offered them the federal surplus in return for abiding by the Canada Health Act. Since mothers wanted daycare, more money might persuade premiers to create more spaces. Since everyone knew that the armed forces had worn-out aircraft and guns, boosting the defence budget by a few billions allowed a few new ones. Meanwhile, voters watched a sardonic Judge Gomery expose a succession of shifty operators associated with the sponsorship scandal. Martin, as Chretien’s former finance minister, had to insist that he was completely unaware of the entire affair and was as eager as anyone to impose full accountability on public officials.

Accountability was popular with Harper and rival party leaders too. After so many Liberal years, the Opposition promises sounded more authentic. If good times continued to yield greater federal surpluses, all parties could promise more spending and tax cuts. To keep ndp backing, Martin cancelled some tax cuts for the wealthy. However, the May 2005 Liberal budget survived a vote of confidence only because Belinda Stronach, a Harper leadership rival, switched sides, as did an ailing B. C. veteran, whom Harper had forced to run as an independent. During the summer, Harper’s handlers worked on his political skills until he had learned how to smUe, shake hands, and make small talk. Meanwhile, the media watched as Martin struggled with a host of inherited issues, from the environment to sponsorship. While the media cruelly labelled him Mr. Dithers, Martin proposed a curb on income trusts, the business world’s latest dodge for tax avoidance, met with First Nations leaders at Kelowna to promise a generous settlement of outstanding issues, and agreed to transfer Canadian soldiers from Kabul to Taliban-infested Kandahar province. Gomery’s first report exonerated Martin and loaded the full blame on Chretien-era officials. By December, polls showed growth in Liberal support. Gomery’s second report, proposing a cure, could be an excellent election send-off To set the stage, Martin warned the ndp that there would be no more deals for them or anyone else. Who, after all, would dare force an election campaign during the Christmas holidays?

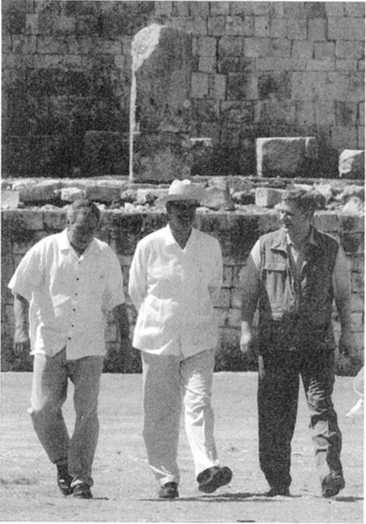

Prime Minister Stephen Harper tours Mayan ruins at Chichen Itza, Mexico, on Thursday, March 30,2006, with President George Bush of the United States, left, and President Vincente Fox of Mexico, right, during one of the periodic meetings of the three partners in the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994.

The NDP’s Jack Layton, that’s who. Liberals duly denounced anyone daring to upset their election timetable. Their holiday plans disrupted, journalists grumbled too. However, most voters saw no problem with an election on January 23,2008, almost a month after Santa Claus had left town. This time, Stephen Harper was prepared. Announcing a policy a day, he seized the initiative and sUenced party troublemakers. Liberals struggled with the Conservatives and waited impatiently for Martin’s platform. Auto union leader Buzz Hargrove paid off some old grievances by denouncing the NDP for risking a Harper government, and urged his members to vote Liberal. In Quebec, Duceppe boasted that Gomery had given the Bloc every seat. In fact, the campaign turned the sponsorship scandal into old news. When Martin announced that he had dropped plans to plug the income-trust loophole, the rcmp announced that it was investigating a Cabinet leak that had allowed some Bay Street operators to reap windfall profits. Who needed Gomery when the Mounties were poking at a scandal at the heart of Martin’s government? When Martin said nothing, voters had heard enough. Moderate weather across Canada denied voters an excuse to stay home and produced the result many had predicted, a Conservative minority: 124 seats, 10 of them from the Quebec City region; 51 seats for Duceppe; and 29 for Layton, the obvious beneficiary of left-Liberal disenchantment. With 30.1 per cent of the vote, the Liberals collected 103 seats, almost all of them east of Manitoba.

On election night, Paul Martin quit as prime minister and Liberal leader. On February 6,2006, Stephen Harper became Canada’s twenty-second prime minister. He announced that his election priorities would rule his government. Accountability regulations might cripple some operations of government, but who, outside the Senate, dared complain? Provinces gained money to cut into hospital waiting lists. The 7 per

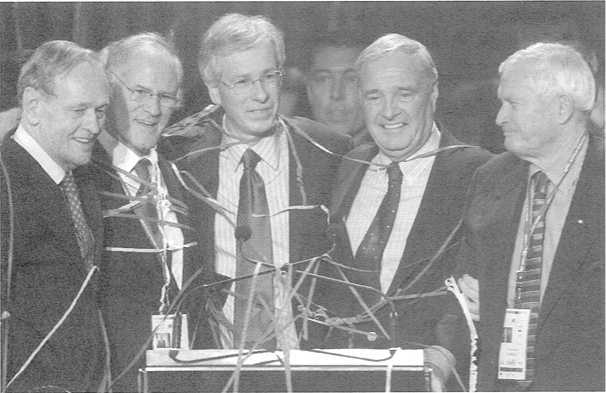

Newly elected Liberal Party leader, Stephane Dion, with former Prime Ministers Jean Chretien (left), John Turner (right), Paul Martin (second right) and interim-liberal Party leader Bill Graham (second left) at the Liberal Convention in Montreal, December 2, 2006.

Cent federal goods and services tax dropped to 6 per cent. A week-long spending spree promised $17 billion for new ships, guns, and aircraft for the Canadian Forces if the Conservatives stayed in office. Photo opportunities with President Bush and a hurried settlement for the long-running softwood lumber dispute reminded Washington that it had a good friend in Ottawa, though Harper, like Martin, opposed missile defence and sent no troops to Iraq. Instead, Canada’s troops lost close to forty dead in Afghanistan in 2006, and Harper’s enthusiasm for the mission allowed many to blame him, not the Liberals, for sending them there. As evidence accumulated of global warming and its devastating impact on the Arctic, Harper’s Bush-like dismissal of the Kyoto Accord began to hurt him. By the end of his first year in office. Conservative support across Canada had slipped and had almost collapsed in Quebec. The environment and Afghanistan were obvious explanations. How could a cool pragmatist turn “green” without enraging his petro-dollar power base?

The Liberals took a year to find a new leader. Major figures from the Chretien and Martin eras tested the water and dropped out. A convention in Montreal heard nine candidates whose inexperience was their common feature. The two front-runners, Michael Ignatieff and Bob Rae, were covertly backed by the Martin and Chretien camps, respectively. Rae had switched from the ndp, but Ontario Liberals let no one forget his troubled years as premier of their province. Ignatieff’s grandfather had been the Russian Czar’s last Minister of Education; he was a scholar-journalist who knew the world better than Canada. Seemingly unaware of the passion mere words had raised

During the long Meech Lake debate, Ignatieff ignored Trudeau doctrine and proclaimed that Quebec was a nation. Gleeful sovereignists jeered at Liberal divisions untU Stephen Harper intervened to declare that Quebec indeed formed “a nation within Canada.” Eventually, the Parti Quebecois told the Bloc to shut up and vote for Harper’s version. Verbal slips and old guard backing froze Ignatieff in his first-ballot standing. Both he and Rae failed to grow. Instead, Stephane Dion, a cabinet workhorse and the sole francophone in the contest, won on the third ballot, if only because so many delegates found him an acceptable second choice. Could a straight-talking but uncharismatic former professor win an election and become prime minister?

He would have to do so in the gloom of what soon became a recession comparable to the Great Depression. Americans inherited the consequences of a massively deregulated system and a national commitment to getting rich without getting sweaty. Under President Bill Clinton, many of the rules established by his New Deal predecessors to curb the mindless greed of the financial world had been abandoned or rejigged. The most powerful economy in the world had no further need of rules that raised the cost of mortgage loans and restrained the invention of paper-backed assets or otherwise constrained greed. A few sceptics warned that the United States was on the brink of a self-inflicted financial disaster, but the 2008 collapse of real estate seemed to catch Wall Street by surprise. One reason was that, as in 1929, although American workers earned dramatically less in real income than they had ten or twenty years earlier, mortgage lenders felt no obligation to find out if would-be buyers could afford their dream homes or even a shabby four-plex. Deregulation had saved lenders the costly and unpopular work of checking on creditors, and the characteristic optimism of American society had launched millions of ordinary people into the linked disasters of unemployment, bankruptcy, and foreclosure.

For once, Canada was not in the same position as its neighbour. The Bank of Canada and the major chartered banks, having often grumbled about over-regulation, could now boast that Canada was a model for its neighbour and for a growing number of European countries caught in a credit crunch. Perhaps few Canadians could identify Reykjavik on a map, but they grabbed their atlases when all of Iceland’s banks went broke. Of course, Canada was never immune when its powerful neighbour was affected, whatever the cause. Once the U. S. recession made American consumers anxious, Canadian exports were among the obvious victims of empty wallets. Politically, Canada’s financial stability helped its dollar climb to parity with the U. S. dollar and even claim a few cents’ premium. By making Canadian goods slightly more expensive

To Americans, this was a source of pride for some Canadians, but it was a further blow to Canada’s economy. While the Liberals may have deserved the credit for regulating Canada’s financial markets and turning a growing deficit into a surplus, the chief political beneficiary was Stephen Harper, a Conservative.

To be fair, he had not forgotten his cautious election promises. Another percentage point off the GST was popular; but Quebec reacted badly when the new government cut its subsidies to cultural activities. The Bloc promised vengeance at the next election, which came on October 14, 2008, after less than three years of a Conservative minority government. Harper’s ruthless control of his party’s caucus and federal civil servants prevented most embarrassments, and Canada’s relative immunity from the 2008 recession led him to emphasize his economic record as a claim to re-election. Even if Canada had again dipped into a deficit, surely that was no more than the Keynesian formula for a rapid and relatively pain-free recovery.

Canada’s fortieth general election was the fourth in eight years, and it had the lowest turnout in Canadian history—59.1 per cent of the electorate. The result was a renewed minority government for the Conservatives, although the three other major parties met soon after the vote to consider uniting and forcing Harper into opposition. This was a legitimate option under a parliamentary system of government, but most of the media dutifully echoed Harper’s outrage, somehow arguing that Harper’s 37.6 per cent of the popular vote easily outweighed the 54.4 per cent who backed his three major opponents. While the ndp was not afraid to make a common front with the Parti Quebecois, the Liberals, licking their wounds after losing 29 of the 103 seats Martin had won two years earlier, rapidly backed off Ideologically, the proposed coalition foundered because the Bloc had to be included. Few Canadians outside Quebec believed than any deal with separatists could possibly benefit their country. Meanwhile, Stephane Dion, denounced for his inadequate English as well as his lack of a persuasive new platform, retreated from politics. Fearful of leaving the choice of a new leader to a party convention, the Liberal managers promptly gave Dion’s job to Michael Ignatieff, a suitably conservative choice for the party establishment.

Stephen Harper had campaigned for a majority in 2008, and according to pre-election polls he might have earned it, except that a majority of Canadians were not yet ready to trust unlimited power to a leader who exercised such relentless control over his party and who had such unquestioned faith in his own judgment. Not since the nineteenth century had such a self-confident ideologue held power in Ottawa.

World History

World History