The Ossets, descended from the Alans, are an Indo-Iranian people presently living in Alania (formerly North Ossetia, or North Ossetiya), a republic in the Russian Federation on the northern slopes of the central Caucasus Mountains. (South Ossetia is part of the Republic of Georgia in the south Caucasus). The Ossets are the largest ethnic group in Alania, thought to be descendants of the ancient Alans, making up just over half the population; Russian Slavs constitute about a third, and the rest are the Ingush and smaller groups. They have a variety of native names, including Digoron, Iron, and Tualhg.

ORIGINS

The Ossets are descended from the ancient people known as the Alans or Alani, classified as Sarmatians.

13th century Mongol invasion; Alans move to mountainous regions.

17th century Alans' descendants, known as Ossets, are ruled by Circassians. 1774 Ossets are ruled by Russians.

1917-20 Fighting between pro-Soviet and anti-Soviet factions in Ossetia

1936 North Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic is created as part of Soviet Union (USSR).

1991 Alania Autonomous Republic established; joins Russian Federation.

LANGUAGE

The Osset language, known as Ossetic (or Ossetian), is Iranian, part of the Indo-Iranian family (the eastern branch of Indo-European). The two modern dialects are Digor and Iron, the more prevalent. Pronunciation has been influenced by the non-Indo-European languages of the Caucasus, Caucasic and Turkic, and the vocabulary has some Russian words.

HISTORY

Because of an invasion of Mongols in the 13th century C. E. surviving Alans moved to moun-

Tain country, where they built a new life. They mixed with other groups in the region, among them Caucasians, and formed three territorial entities: Digor in the west, Tuallag in the south, and Iron in the north. In their rugged homeland they managed to maintain some independence from Mongol rule, which lasted until the 15 th century In the 17 th century Digor fell under the rule of the Karbardians, a subgroup of Circassians of the North Caucasus. Tualleg was ruled by Georgians from the South Caucasus. In 1774 the Ossetian homeland became part of the Russian Empire. The Ossets tended to support the Russian presence over that of the Muslim Turks (see Turkics) competing for the region.

In 1917-20 during and after the Bolshevik revolution the region became an administrative district of the North Caucasus known as the Mountain Republic. North Ossetia became an autonomous region in 1924, redefined as the North Ossetian Autonomous soviet socialist Republic in 1936. In 1991 after the breakup of the Soviet Union the region became the Alania Autonomous Republic within Russia and subsequently a republic within the Russian Federation (see Russians: nationality).

CULTURE

Many of the Ossets earn a living in agriculture, especially of grains and fruit. They also raise and breed cattle. Lumbering also provides income. Industry in the region includes mining, metallurgy, and machinery Some Ossets are expert woodworkers.

Ossets have a tradition of folk epics in the Ossetic language. Many of them relate tales about the Narts, hero warriors. The national poet, Kosta Khetagurov, of the 19th and 20th centuries helped establish a literary form of Ossetic, the dialect Iron, written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

The majority of Ossets are Christians, as a result of the influence of peoples of Georgia, where Christianity was introduced in the fourth century.

With family and cultural ties with Ossets in Transcaucasia some Ossets and others in Alania have sought to unify the regions known as North and South Ossetia, but both the Russian and Georgian governments have opposed such a move.

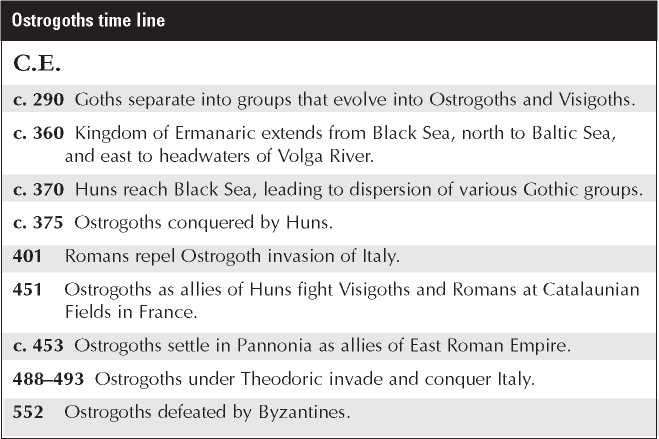

Ostrogoths (Ostrogothi; Ostragothae; Ostrogothones; East Goths; Greutungi; Greutungs; Greutungians; Greuthungi; Greuthungs)

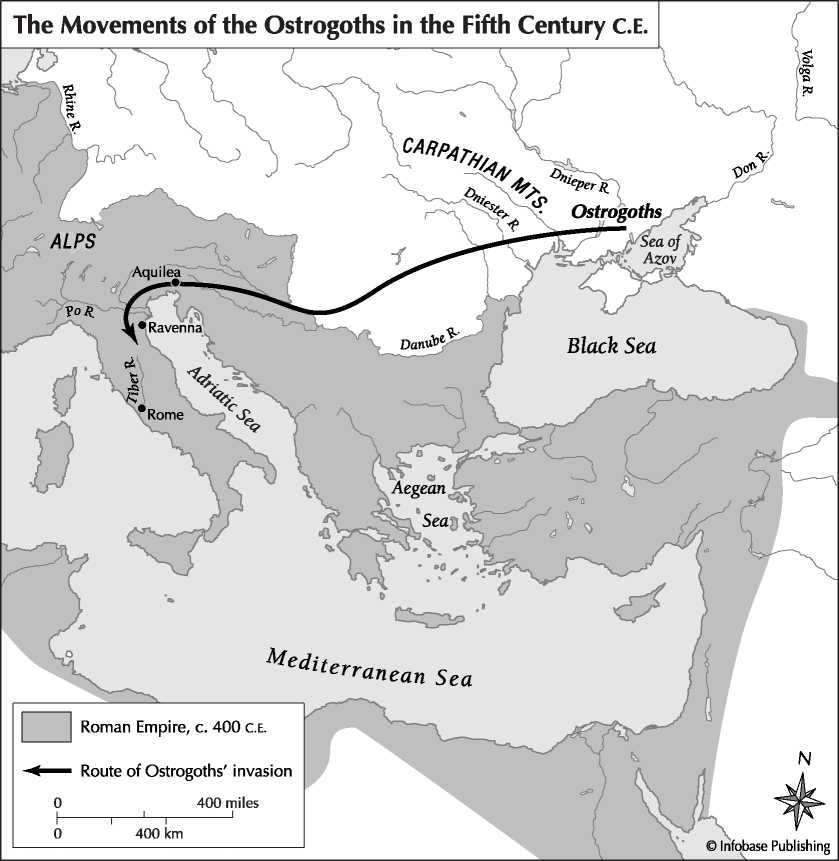

The Ostrogoths were one of the two major groupings of Goths—a people classified as eastern Germanics—the other the Visigoths. From the late third century C. E. their histories were separate; the Ostrogoths originally inhabited the region north of the Black sea east of the Dniester River (part of modern Ukraine and Belarus). In the fourth century they dominated a territory extending north to the Baltic Sea and east to the Volga River. Their founding group, known as the Greutungi, were allied for about 80 years with the Huns, then with the Byzantines of the Eastern Roman Empire. They became the dominant political entity on the Italian Peninsula in the late fifth century and first half of the sixth century.

ORIGINS

The tribe after which the Goths probably took their name, the Gutones, are thought to have originated in scandinavia before migrating southeastward into eastern Europe. The approximate date given for the start of two distinct Gothic traditions is 290 C. E., after defeat by the Romans in 271. They later became known as the Ostrogoths (from the Low Latin Ostrogothi for eastern Goths) and Visigoths (from Low Latin Visigothi, good goths). The family of Amali (Amal, Amaling) were the founders of the Gothic kingdom that eventually would evolve into the Ostrogoths,

OSTROGOTHS

Location:

East of Dniester River in Ukraine and Belarus; western Hungary; northern Croatia; Slovenia; eastern Austria; Italy

Time period:

C. 290 to 552 C. E.

Ancestry:

Gothic (Germanic)

Language:

Germanic

Ostrogoths used this cloak pin in the fifth century C. E. (Drawing by Patti Erway)

A polyethnic group, including steppe peoples originally out of Asia. This confederation was originally known as the Greutungi. In about 325 they were conquered and then absorbed by the Huns into the Hunnic confederation as mostly loyal soldiers, but after the confederation collapsed on Attila’s death in 453 they went their own way as a newly reconstituted group and became known to other Europeans as the Ostrogoths.

LANGUAGE

The Ostrogoths spoke Gothic, a dialect of the East Germanic language group, which had become distinct by about the fourth century C. E. Gothic, now an extinct language, probably ceased to be spoken as the Ostrogoths and Visigoths lost their distinctive identities and were absorbed by other peoples during the Middle Ages.

The Kingdom of the Greutungi: Proto-Ostrogoths

The first Amali leader of the Greutungi—the founding group of proto-Ostrogoths—in the late third century C. E. was Ostrogotha; little is known about him and he may have been no more than a legendary, semimythical figure such as many Germanic tribes claimed as founding father. It was probably in this tradition that he was considered by later Ostrogoths to be their founder as the first of the royal lineage known as the Amali. During the next century under Ermanaric the first Greutungi king known to history, the proto-Ostrogothic people expanded their territory, centered along the Dnieper River, from the Black Sea north to the Baltic Sea and from the Dniester east to the Volga River in present-day western Russia. This vast region included traditional trade routes

Theodorie: Germanic King of Italy

Theodoric was born in the Roman province of Pannonia in about 454 C. E., the son of Thiudemir. As an eight-year-old, he was sent to Constantinople as a hostage. He reportedly lived there until he was 18, gaining an education unprecedented for an Ostrogoth, learning about the workings of the Roman Empire and the imperial system of government. Shortly after returning to his people Theodoric became co-ruler of the Ostrogoths with his father, until he inherited the throne in 474.

Theodoric was much more successful in playing the political games with the Romans than the Visigoth Alaric had been in the early years of the fifth century, and eventually he won the position of magister militum (master of soldiers) and was even adopted into the imperial Flavian house. But he also knew the importance of impressing the Romans with his military might. Thiudemir and Theodoric led an Ostrogoth contingent southward onto the Balkan Peninsula and forced Emperor Leo I to grant them additional territory in Macedonia.

Over the years the Ostogoths and Byzantines of the Eastern Roman Empire maintained a shaky truce. The Byzantines had not given up the ambition of regaining Italy for the empire, and at Emperor Zeno’s request Theodoric invaded Italy in 488 and defeated Odoacer, the first Germanic ruler of Italy. By 493 Theodoric occupied nearly the entire Italian Peninsula and declared himself king with the official title Flavius Theodericus rex. His title in Gothic was Thiuda-reiks, a highly unusual combination of the archaic Germanic term thi-udans used for a kind of sacred king among early Germans, with the term reiks, related to the Latin rex for “king.” He established Ravenna as his capital. Through military positioning, diplomacy, and marriage Theodoric forged an alliance with other Germanic powers of the day, including the Alamanni, Burgundii, Franks, and Visigoths.

Theodoric honored Roman traditions even as he built Ostrogothic power on the Italian Peninsula. He promoted a dual system in which his Germanic soldiers were generally segregated from the local population, and the latter were encouraged to develop commerce and agriculture. Although an Arian Christian, he demonstrated tolerance for other Christian sects. He erected the impressive mausoleum of Theodoric in Ravenna, which still stands. After his death in 526 his daughter, Amalasuntha, ruled as regent to her son, Athalaric. Dietrich von Bern, a character in the German epic poem Nibelungenlied, is based on Theodoric.

Among various peoples, north and south, east and west.

The arrival of the conquering Huns along the Black Sea in the 370s led to a shift in power in the region as the proto-Ostrogothic armies were unable to withstand the Hunnic onslaught. Reportedly Ermanaric committed suicide, possibly as a sacrifice to the gods for the safety of his people. In the following years most of his people were absorbed into the Hunnic confederation. Some among them managed to flee to Roman-held territory in Pannonia (roughly modern Hungary), but most became loyal allies.

In 401 a group of Greutungi Goths under Radagaisus, along with some Vandals and QUADI, invaded the Roman province of Raetia (parts of present-day Austria and Switzerland) and threatened Italy. Stilicho, a Roman general of Vandal ancestry, managed to repel them before they crossed out of the Alps. The next year he defeated the Visigoths under Alaric I in northern Italy.

In the following century reportedly tens of thousands of Greutungi Goths fought alongside Attila in his invasion of western Europe. Three brothers of the Amal line—Thiudemir, Walamir, and Widimir—led the Greutungi contingent. In 451 the Visigoths fought against them as allies of the Romans at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, south of modern Chalons-sur-Marne in present-day France. After the defeat of the Huns and Attila’s death in 453 some of the Greutungi Goths, now known as Ostrogoths, settled in Pannonia as foederati (federates) of the Byzantines. By this time many of them were adherents of Arian Christianity.

Pannonia had been reduced by war into a region with a barely subsistence agricultural economy, making the Ostrogoths dependent for their welfare on payments from the eastern Romans who would evolve into the Byzantines. Thus whenever these were not forthcoming the Ostrogoths would go on raids within the empire. As a result of one of these raids Theodoric, the eight-year-old son of Thiudemir, was sent to Constantinople (modern Istanbul) as a hostage, and spent about 10 years there.

In the ensuing years the Ostrogoths competed for territory with the SCIRI and Gepids, also former allies of the Huns. In 469 the Ostrogoths defeated the Sciri. Theodoric (see sidebar) became co-ruler of the Ostrogoths with his father in 471, shortly after he returned to his people, and began a period of both warfare and alliance with the Romans.

In 476 the Scirian ruler Odoacer, leading an alliance of Sciri, Heruli, and Rugii, captured Ravenna, the capital of the Western Roman Empire, causing the deposition of the last Western emperor, Romulus Augustus. In a form of “divide and conquer,” the Byzantine emperor Zeno commissioned Theodoric to quell Odoacer, hoping to reduce the power of both by setting them at war with one another. Theodoric and Zeno knew each other from the former’s days as a hostage.

In 488 Theodoric’s forces defeated the Gepids in battle at Sirmium near present-day

Seremska, Serbia, on the Sava River and then proceeded southward into Italy. The next year Theodoric defeated Odoacer’s forces at Aquileia and Verona and besieged Ravenna for two and a half years. Odoacer admitted Theodoric to Ravenna under a truce, and the two agreed to rule Italy jointly. But Theodoric personally killed Odoacer and seized complete power, establishing in 493 a kingdom with Ravenna as the capital. He continued to pay homage to the Byzantine emperor, to maintain the legitimacy of his kingdom, nominally holding Italy until Zeno should return. Zeno died before he could accomplish this, and his immediate successors were too preoccupied with their Eastern Empire to trouble about Italy, by now an economically feeble backwater.

Theodoric’s rule rested squarely on Roman traditions; he took as his official title Flavius Theodericus rex and retained Roman governmental structures. However, to maintain the loose confederation of Germanic peoples he had forged, partly through marriage, which included the Visigoths, Alamanni, Burgundii, and Franks, he ruled through a dual system, keeping his Germanic troops apart from the Roman populace and commanding them as the general of a Roman army. Theodoric’s way of balancing Gothic with Roman elements, in which the two were paired but not melded, as would happen in the next century with the Franks under their king, Clovis I. The Roman-educated Theodoric perhaps understood that his people, whose very identity had been honed by being part of Theodoric’s hordes, could not be expected to become Romanized overnight.

On the death of Theodoric in 526 his grandson, Athalaric, became king and his daughter, Amalasuntha, regent. She allied herself with the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, arousing the opposition of Ostrogothic nobles. When she was banished, then killed, Justinian sent his general Belisarius, who had defeated the Vandals in North Africa. Belisarius invaded Italy by way of Sicily and occupied Rome in 536. When Belisarius was recalled in 541, the Ostrogoths rose up under Totila. In 552 the Byzantine general Narses defeated Totila’s forces at Taginae (near modern Gubbio), killing Totila and regaining Italy for the Byzantines. In 555 all Ostogothic resistance ended. In 572 the Lombards, another Germanic people, invaded and took control of Italy.

The Ostrogoths lost their political identity and were absorbed into other tribes.

CULTURE (see also Germanics) Government and Society Ostrogothic Ethnogenesis The Ostrogoths, like most other Germanic tribal groups, while being made up of fragments of other tribes that previously had come apart in the exigencies of the migration period—war and movement into new territories—saw themselves as belonging to a distinct ethnic people with their own royal lineage, the Amali, founded by the semi-mythical Ostrogotha, and shared history. The crux of Ostrogothic ethnogenesis lay in the experience of being defeated by the Huns, the self-sacrifice of their king Ermaneric, and their subsequent experience as allied warriors of the Hunnic confederacy. Attila with great shrewdness flattered the Greutungi leaders of the Ostrogoths, counting on them to control the rest of the Germanic warriors who had joined him. Many Ostrogothic elite graves from this time contained eagle-shaped plaques whose style shows steppe art influence. They may have been badges showing allegiance to the Hunnic overlords.

Theodoric and Roman Institutions Perhaps the greatest Germanic king of his age, Theodoric sought to protect and extend the benefits of Roman civilization and at the same time preserve his people’s sense of their Ostrogothic identity. Thus he lavishly supported public works, restoring seaports and aqueducts with the sense of civic duty that had been a central tenet of Roman civilization; took steps to promote the economy; and acted to safeguard Roman customs and institutions, especially the senate. He appointed Romans to important administrative posts. At the same time he segregated his own people under their own commanders in enclaves in northern and central Italy—perhaps also to eliminate temptations to raid—where they could live according to custom.

Military Practices

Ostrogoth warriors, influenced by Asian steppe people, typically fought from horseback, often with lances.

Theodoric established the exercitus Gothorum, a Roman army in name although under his command, which incorporated soldiers from all over the Roman Empire.

Dwellings and Architecture

During the period they lived near the Black Sea the proto-Ostrogoths built many settlements, which have been identified archaeologicalfy. In present-day Moldova alone 150 are known. Hundreds more have been found in a large territory reaching from the Dnieper River to central Transylvania and from the region of the rivers Pripet and Bug to the Lower Danube. Many of their settlements were built on river-banks and were not fortified. Their material remains are known archaeologically as the Cerneachov culture, after a cemetery at the Dnieper River. About 1,500 burials of this culture have been found.

It is a measure of the caliber of Theodoric that he esteemed the great philosopher Boethius, one of the founders of medieval philosophy, and made him a consul in 510. However, another measure of the Ostrogothic king is that some 20 years later, when Boethius was accused by his enemies of plotting to restore Roman (that is, non-Ostrogothic) rule, Theodoric believed his accusers and ordered Boethius imprisoned and later executed. During his imprisonment Boethius wrote De consolatione philosophiae (Consolation of Philosophy). (This work would later be translated into Old English on the reign of Alfred the Great of the Anglo-Saxons, another of the series of great kings produced by Germanic peoples in the early Middle Ages, and would be influential in that society as well.) Boethius can be said to have flourished in part because of and in part despite Ostrogothic rule, his ambivalent experience with Theodoric a sign that the Ostrogoths had not quite left their barbarian past behind them.

Another Roman scholar patronized by Theodoric was Cassiodorus, who served as his secretary, among other posts. Cassiodorus wrote a History of the Goths, of which only a digest remains. Dionysius Exiguus (Dennis the Small), a Dacian monk and friend of Cassiodorus, laid the foundations of ecclesiastical or canon law that would be followed throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, by translating from Greek into Latin 401 ecclesiastical canons, including the apostolical canons and the decrees of the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, and others. He also played a major role in determining the method of calculating the date of Easter.

As evidenced by the achievements of these scholars the Ostrogoths, whatever their failings, managed to preserve a degree of peace, a breathing space, in which crucial work for the preservation of Roman culture and institutions could take place, before their successors as rulers of Italy, the considerably less Romanized Germanic people the Lombards, swept much of it away.

The Ostrogoths suffered in their relations with their Roman subjects because the religion they had adopted, in abandoning the paganism of their ancestors, was Arian Christianity, considered by the Roman Church a heretical creed.

Saint Benedict of Nursia, the founder of Western monasticism, lived during the latter period of Ostrogothic rule in Italy, having grown to young manhood by the time of Theodoric’s death. However, he found Rome, where he had grown up as the son of noble Roman parents and studied for a time, such a degenerate place that he withdrew to an isolated area, where he lived in a cave, then finally to northern Italy, where he founded the monastery of Monte Cassino. This suggests he had little to do with the Ostrogoths and their rule; indeed, when King Totila visited him, Benedict rebuked him severely as a wicked man and prophesied his further career and his death in 10 years. It is said that Totila was so impressed with Benedict that he was never so cruel again as he had been in the past. But at least the Ostrogoths had procured a period of relative peace in which Benedict could pursue his holy work.

The career of the Ostrogoths in Italy shows what might have been achieved in preserving the Roman Empire, which had done so much to bring the great Germanic confederacies into being. The continued violent movements of peoples in the sixth century and for centuries afterward made this impossible. It would be left to the Frankish Carolingians, viewing the imperial tradition from across a dark divide of several centuries of destruction, to bring into being the Germanic dream of reviving the empire, and to achieve a true melding of Germanic and Roman elements and traditions. This fusion proved to be more enduring than the dual system attempted by Theodoric.

Further Reading

Samuel Barnish and Federico Marazzi, eds. The Ostrogoths from the Migration Period to the Sixth

Century: An Etnographic Perspective (Woodbridge, U. K.: Boydell & Brewer, 2004).

Thomas S. Burns. A History of the Ostrogoths (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991).

T. Hodgin. Theodoric the Goth: Barbarian Champion of Civilization (New York: Gordon, 1977).

World History

World History